The Daring Heist of D.B. Cooper

Podcast: Play in new window | Download | Embed

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | RSS | More

Feeling a slight bump up in the cockpit, the pilots of Northwest Orient Airlines Flight 305 looked at each other nervously as rain pelted against their windshield at around 200 miles per hour…a relatively slow speed for a Boeing 727. They didn’t yet know that that bump meant their ordeal of the past several hours was just about over; that they, along with their flight engineer and flight attendant, would live to see another day—because the man known only as Dan Cooper had just exited the plane by leaping from the rear staircase in mid-flight, with a parachute and $200,000 strapped to his body, never to be seen again.

Who was Dan Cooper really? Did he survive his fateful fall from the sky? And whatever happened to all that money? It was exactly 50 years ago this month that Dan Cooper, the man, became D.B. Cooper, the myth, by leaping from a perfectly good airplane and right into the pages of Washington State, and truly, national history. Thousands of people have searched for evidence in the case, trying to solve the only unsolved American skyjacking…ever.

Setting the stage

Now, as with most retellings of historical events, I like to begin by providing a little context. After all, who are we to judge the events of yesterday by today’s “enlightened” standards without knowing the full details of what life was like during that time. In that vein, let’s talk about skyjackings and why we don’t really hear about them much today.

During the 1960s and 70s, airplane hijacking (known as “skyjacking”) was fairly rampant in the United States. Remember, this was at a time when domestic flights didn’t require baggage checks or metal detectors of any kind. You didn’t even need proper identification to purchase a ticket. Anybody could walk into any airport in the country, buy a plane ticket with cash, and bring anything they wanted on board.

Also during this time, the United States had a very tense relationship with Cuba, its island neighbor south of Florida. In a three-year period between 1968 and 1971, more than 80 flights originating in the US were skyjacked and directed to fly to Cuba. Most of those were politically motivated terrorists or criminals, as the communist country was off limits to travelers coming from the United States. The word skyjacking became a well-known term in American culture at the height of the Cold War.

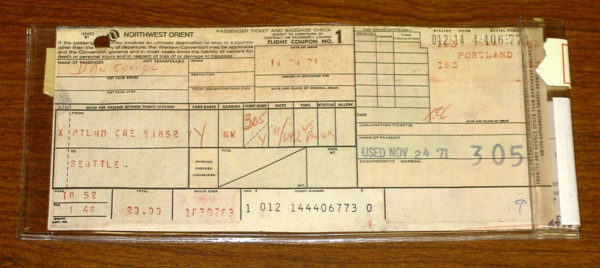

So, let’s zero in on November 24, 1971, in Portland, Oregon, when the first events of the D.B. Cooper storyline begin to unfold. It’s the day before Thanksgiving, and at 2 p.m. that day, a light-skinned man estimated to be in his mid-40s walked into Portland International Airport. Eyewitnesses describe him as about 6-feet tall and 180 pounds, wearing a black business suit, black tie, brown loafers, a dark overcoat, and carrying a black briefcase. He approached the Northwest Orient Airlines ticket counter, identified himself as Dan Cooper, and purchased a one-way ticket to Seattle, Washington, with $20 cash.

When Flight 305 began to board, Cooper entered second-to-last and made his way past 35 other passengers to the very back seat, seat 18-E, of the Boeing 727. After getting settled, Cooper lit a cigarette and waived down flight attendant Florence Schaffner, ordered a drink and passed her a note which she put in her pocket. Stewardesses (as they were called at the time) were used to getting hit on by travelers, so Florence assumed this was yet another lonely businessman trying to get a date. Cooper, on the other hand, insisted that she read the note right then and there…which she did. “Miss, I have a bomb here and I would like you to sit by me,” which is possibly the most pathetic way I’ve ever heard to get to know someone a little better.

Florence read the note several times thinking it must be a joke. She asked Cooper if he was joking, to which he replied, “No miss. This is for real.” At that moment, 3:07 p.m., Flight 305’s wheels lifted off the tarmac and the plane began its short trip to Seattle-Tacoma International Airport…usually a short, 30- to 40-minute trip. Wondering where her coworker was, Flight Attendant Tina Mucklow made her way to the back of the plane to find a nervous Florence seated next to a passenger. As she did so, Cooper donned a pair of black wraparound sunglasses. Florence handed the note to Tina, who relayed what was happening to the pilots via intercom from the rear of the aircraft.

To Florence’s horror, Cooper then opened his briefcase and revealed what looked like eight sticks of dynamite bundled together with tape and wired to a battery. He held up a loose wire and told Florence he could detonate the bomb at any time. After shutting the briefcase again, Cooper instructed Florence to write down his list of demands and then sent her up front to relay them to the captain. He asked for $200,000 in negotiable American currency by 5 p.m. put into a knapsack. The denominations of the bills were not important. He demanded two back parachutes and two front parachutes, a fuel truck ready and waiting in Seattle, and Cooper’s now-infamous skyjacking of Northwest Orient Airlines Flight 305 had begun.

Flight 305

The captain, William Scott, radioed the situation to Seattle-Tacoma air traffic control and instructed Florence to stay in the cockpit for the rest of the flight. Sea-Tac relayed the information to the Federal Bureau of Investigation, who called Northwest Orient Airlines president Donald Nyrop to brief him. Nyrop’s concern for his passengers and his airplane prompted him to request the FBI comply with Cooper’s demands.

Cooper also told the pilots they weren’t to land until everything was ready on the ground in Seattle. However, it was taking more time than the duration of the 30-minute flight to procure everything Cooper had asked for. The last thing anyone—including Cooper—wanted right then was panic in the cabin, so Captain Scott and First Officer William Rataczak told passengers they were experiencing a mechanical issue and had to circle to burn off fuel before landing.

While they circled the skies above Seattle, the FBI found a flight school in Issaquah that provided them with two backpack-style parachutes, and two reserve chutes worn on the front of the body. Why Cooper had asked for four parachutes, no one may ever know, but Seattle Sky Sports delivered on the demand. Meanwhile, Seattle’s First National Bank (known as “SeaFirst”) began loading $200,000 into a heavy canvas bank bag after making note of the money’s identifying marks.

FAST FACT: Banks at that time would often keep larger amounts of cash stored in bundles for exactly this purpose. In the case of a robbery, kidnapping, or ransom of any kind, bank staff would be able to grab one of the bundles – designed intentionally to look like it was hastily gathered rather than prepared in advance – and use it immediately. Each bill in the bundles had been photographed and had its serial numbers logged so the bank could relay that information to area banks, casinos, racetracks, and other places the bills might turn up. If used and spotted, the perpetrator could more easily be hunted down and captured.

After circling for two hours, Flight 305 finally landed at Sea-Tac and taxied to a remote area of the tarmac. An airport employee drove a stair car to the front of the plane and Tina Mucklow alone exited to retrieve the money waiting with a nearby FBI agent. Upon returning to the plane with the money, Cooper quickly realized a problem. Though he didn’t specify bill denominations in his demand, he expected 2,000 one-hundred-dollar bills. Instead, he found 10,000 twenty-dollar bills, which weighed about 22 pounds…more than he anticipated. He had also requested a knapsack, known more commonly today as a backpack, but received the money instead in the canvas bank bag.

Nevertheless, with money in hand, Cooper agreed to release the rest of the passengers, who were still unaware that they had been held hostage for nearly three hours. Tina Mucklow also exited once again and returned with the four parachutes. She nervously asked Cooper where their next destination would be, and Cooper replied, “Don’t worry, miss. We’re not going to Havana.” Tina also asked him if he had a grudge against the airline, to which he allegedly replied, “I don’t have a grudge against your airline, miss. I just have a grudge.”

Tina, Florence, and others who interacted with Cooper that day all described his as being calm, polite, and well-spoken, not being nervous at all. They said he was rather nice, thoughtful, and never cruel or nasty. He even tried to tip one of them after paying for his second bourbon and soda. But as the minutes ticked by on the ground in Seattle, Cooper began to grow impatient as a second and then third fuel truck was called to fill the tanks. After ordering the crew to close all the window shades in the plane so he couldn’t be seen by law enforcement snipers, Cooper began outlining his idea of a flight plan to the pilots.

The jump

Cooper’s big plan was to fly the 727 to Mexico City at an altitude of just 10,000 feet, at the slowest possible speed to remain aloft, and with the landing gear and rear staircase down the entire time. But pilots warned him that to do so would both increase drag and burn fuel faster, forcing them to refuel again before reaching Mexico City, not to mention being a huge safety issue. Cooper eventually agreed to refuel in Reno, Nevada, and to take off with the rear stairs retracted. At the time, the Boeing 727 was the only commercial airliner that had an attached staircase at the back of the plane, which allowed new passengers to board from the rear while existing passengers deplaned from the front.

By the time Flight 305 finally took to the skies above Seattle once again, it was 7:36 p.m., and a chilly rainstorm had descended upon the Pacific Northwest. The temperature was about 40-degrees and falling fast. On board were the pilot and first officer, Scott and Rataczak, Flight Engineer Harold Anderson, Flight Attendant Tina Mucklow, and of course, the man calling the shots: Dan Cooper, who began strapping on one of the larger backpack parachutes—an NB-8 military model obtained from the Issaquah flight school. Afterward, he opened one of the smaller front parachutes and cut out the paracord with a pocketknife. Since the Feds had delivered his money in a bank bag instead of a backpack, he didn’t have a way of holding onto and securing it, so he fashioned a strap around the bank bag using the parachute cord he’d cut.

Five minutes into the flight, Cooper instructed Tina to open the rear staircase in mid-flight. She refused, citing her fear of being sucked out. Cooper acquiesced, and instead sent her to the cockpit with instructions that no one come back beyond the first-class area. The last time anyone laid eyes on Dan Cooper, he was tying the bank bag around his waist with the parachute cord and steeling himself for what inevitably had to come next.

At 7:43 p.m., pilots noticed a warning light indicating the rear stairs had been deployed. At 8:03 p.m., the external temperature gauge in the cockpit recorded a temperature of 19.4 degrees Fahrenheit. Just after 8:10 p.m., the flight crew felt that bump in the airplane—which they assumed was Cooper leaping from the rear staircase into the pitch-black night. Noting their position on their instruments, they saw they were somewhere over the forests of southwestern Washington. Following their instructions, they did not peek into the passenger area to see if Cooper was still aboard. He did, after all, have what looked like a bomb capable of destroying the plane and everyone aboard in an instant. Once they landed in Reno, FBI agents stormed the plane, evacuated the crew, and thoroughly searched from nose to tail. But skyjacker Dan Cooper was nowhere to be found.

Evidence left behind

Cooper took the original note he’d passed to Florence with him, but he left behind his plane ticket, his black JC Penney clip-on tie, seven Raleigh brand cigarette butts, a few strands of hair on the back of his seat, and some partial fingerprints. To this day, investigators have been unable to make a positive match to anyone using the hair, fingerprints, or cigarette butts. The following morning, the FBI and local authorities conducted a massive sweep of the projected area in southwest Washington where it was believed Cooper may have landed.

In an experimental re-creation, with the same aircraft used in the hijacking in the same flight configuration, FBI agents pushed a 200-pound sled out of the open airstair and tracked where it fell to earth. They estimated Cooper’s landing zone within an area on the southernmost outreach of Mount St. Helens, a few miles southeast of Ariel, Washington, near Lake Merwin, an artificial lake formed by a dam on the Lewis River.

FAST FACT: Ariel, Washington, hosts an annual event known as D.B. Cooper Days at the town’s General Store and Tavern. Case enthusiasts, amateur investigators, true crime buffs, authors, and fans of the unsolved skyjacking gather to discuss the evidence, their hypotheses, conspiracy theories, and other Cooper-related topics while enjoying beer, food, and live music. There’s an annual D.B. Cooper look-alike contest and the town’s population generally swells from about 800 to well over 1,000 people. While you’re visiting Ariel, there are other things to do nearby as well, such as enjoying the benefits of Lake Merwin, visiting the historic Cedar Creek Grist Mill, climbing Mount St. Helens, or touring one of its visitor centers, or experiencing the LeLooska Foundation and Cultural Center’s portrayal of pacific northwest Native American life.

Search efforts focused on Clark and Cowlitz counties, encompassing the terrain immediately south and north of the Lewis River. FBI agents and sheriff’s deputies from those counties searched large areas of the mountainous wilderness on foot and by helicopter, carried out door-to-door searches of local farmhouses, and ran patrol boats along Lake Merwin and Yale Lake, the reservoir immediately to its east. No trace of Cooper, nor any of the equipment presumed to have left the aircraft with him, was found.

The FBI also coordinated an aerial search, using fixed-wing aircraft and helicopters from the Oregon Army National Guard, along the entire flight path from Seattle to Reno. Although numerous broken treetops and several pieces of plastic and other objects resembling parachute canopies were sighted, investigators found nothing relevant to the hijacking.

Shortly after the spring thaw in early 1972, teams of FBI agents aided by some 200 United States Army soldiers from Fort Lewis, along with United States Air Force personnel, National Guardsmen, and civilian volunteers, conducted another thorough ground search of Clark and Cowlitz counties for eighteen days in March, and then an additional eighteen days in April. A marine salvage company used a submarine to search the 200-foot depths of Lake Merwin. Two local women stumbled upon a skeleton in an abandoned structure in Clark County, but that was later identified as the remains of a teenaged girl who had been abducted several weeks before. Ultimately, the extensive search and recovery operation uncovered no significant material evidence related to the hijacking.

A month after the hijacking, the FBI distributed lists of the ransom serial numbers to financial institutions, casinos, racetracks, and other businesses that routinely conducted large cash transactions, and to law enforcement agencies around the world. Northwest Orient offered a reward of 15% of the recovered money, to a maximum of $25,000. In early 1972, the US Attorney released the serial numbers to the general public. The following year, The Oregon Journal republished the serial numbers and offered $1,000 to the first person to turn in a ransom bill to the newspaper or any FBI field office. In Seattle, the Post-Intelligencer made a similar offer with a $5,000 reward. The offers remained in effect until Thanksgiving 1974, and though there were several near matches, no genuine bills were ever found. Cooper, it seems, had successfully vanished.

A late break in the case

Though investigators continued to search for evidence and follow hundreds of potential leads to their inevitable dead ends, it was another 8 years, 2 months and 19 days before there was a substantial break in the case. On February 10, 1980, an 8-year-old boy named Brian Ingram was vacationing with his family along the Columbia River at a place called Tena Bar, about nine miles downstream from Vancouver. While digging in the sandy beach, Ingram unearthed three packets of banded 20-dollar bills, largely disintegrated from lengthy exposure to the elements. FBI technicians confirmed that the money was indeed $5,800 of the Cooper ransom: two packets of 100 twenty-dollar bills each, and a third packet of 90, all arranged in the same order as when given to Cooper.

The discovery injected new life into the investigation, but also created a host of new questions in need of answers. They knew the bills discovered by Brian Ingram were from the Cooper skyjacking, but they were in an unexpected and previously unsearched area. Teams of FBI agents and local police scoured the riverbank the next day, digging up most of the entire bar where the $5,800 was found…but no additional evidence surfaced as a result.

So how did just a portion of the money end up buried in the sand, miles away from where investigators calculated Cooper might have landed? There was no shortage of theories. One popular suggestion was that the money had been dug up from the bottom of the river and deposited on the riverbank during a dredging operation conducted in 1974. It was a sound theory, but geologists quickly confirmed there were two separate dirt layers between the money and the layer of dredge tailings, indicating the money had arrived there after the dredging operation.

There’s also the fact that pilots in the air that fateful night disagreed about the windspeed, direction, and even the path that Flight 305 was on. FBI agents began to suspect that perhaps Ariel and Lake Merwin were not where Cooper likely landed, and that his touchdown point was actually closer to the Washougal River several miles southeast.

That led to another theory that the bank bag had landed in the Washougal River and spent the next several years washing downstream until it fed into the Columbia. At some point, the canvas bag must have degraded to the point that several bundles of cash escaped and floated ashore at Tena Bar. However, scientific experiments using the same rubber bands as those found on Brian Ingram’s bundles deteriorated and broke apart after less than a year underwater, indicating the bundles did not spend 8 years rolling downstream at the bottom of the Washougal.

FAST FACT: Six years after unearthing $5,800 of Cooper’s stolen money, the FBI, Northwest Orient Airlines, and the Ingram family agreed to split the find equally between them. Northwest gave its portion to its insurance company, the FBI retained fourteen bills as evidence, and Ingram kept his share until 2008, when he sold fifteen of his bills (remember, that’s only $300 bucks) at an auction and made $37,000. Aside from a placard printed with instructions for lowering the aft stairs of a 727 that was found by a deer hunter near a logging road about 13 miles east of Castle Rock, Washington, in November 1978—the $5,800 in ransom money remains the only confirmed physical evidence from the hijacking ever found outside the aircraft.

Just three months after Brian Ingram discovered some of Cooper’s money, the massive eruption of Mount St. Helens in May of 1980 pushed so much mud and debris down the areas waterways that many believed any evidence of the Cooper hijacking must have been buried for all eternity.

Unusual suspects

While investigators continued to search for any physical evidence on the ground, others were looking into possible suspects for the brazen crime. The FBI considered hundreds upon hundreds of possible suspects, one of the first of which was an Oregon man named D.B. Cooper. Though he was quickly ruled out, a local reporter in a rush to meet a deadline confused the person of interest with the skyjacker’s alias, a wire service reporter then repeated the error to media outlets nationwide, and the name D.B. Cooper became the most widely remembered moniker instead of Dan Cooper, the supposed pseudonym used by the skyjacker himself.

FBI profilers began making educated assumptions based on several details they hoped would lead to the real identity of the man responsible. Evidence suggested that Cooper was knowledgeable about flying technique, aircraft, and the local terrain. He demanded four parachutes to force the assumption that he might compel one or more hostages to jump with him, thus ensuring he would not be deliberately supplied with sabotaged equipment (even though one of the reserve chutes he was given was actually a training chute that was sewn shut…something an experienced skydiver would have checked for).

Cooper appeared to be familiar with the Seattle area and may have been an Air Force veteran, based on testimony that he recognized the city of Tacoma from the air as Flight 305 circled Puget Sound, and his accurate comment to Mucklow that McChord Air Force Base was approximately twenty minutes’ driving time from Seattle-Tacoma Airport.

Some posited that Cooper may have been a thrill seeker who made the jump just to prove it could be done. Others believed he was very likely desperate for money, enough to commit the crime despite the considerable risk. One FBI agent suggested the possibility that he might have been an aircraft cargo loader. Such an assignment would have given him knowledge and experience in the aviation field; and loaders—because they throw cargo out of flying aircraft—wear emergency parachutes and receive rudimentary jump training.

Between 1971 and 2016, the FBI processed more than a thousand suspects, including an assortment of publicity seekers and alleged deathbed confessors. One of the most compelling was a man named Richard Floyd McCoy, Jr., who staged a similar “copycat” skyjacking just four months after Cooper’s. While the crimes were nearly identical, there was simply too much evidence to the contrary to consider him a suspect. First, McCoy was about half of Cooper’s estimated age, and he was confirmed to be at his home in Provo, Utah, for Thanksgiving dinner…the day after the Cooper heist in 1971.

A man named Lyle Christiansen became convinced in 2003 that his late brother, Kenneth Christiansen, must have been D.B. Cooper. Kenneth was an ex-Army paratrooper, he worked as a mechanic for Northwest Orient Airlines, he was based for a time in Seattle, and was in his 40s at the time of the hijacking. But the FBI ruled him out on account of the poor similarity to eyewitness descriptions of Cooper and the complete lack of physical evidence beyond the purely circumstantial.

Another suspect, Sheridan Peterson, enjoyed remarking that he may have been the criminal known as D.B. Cooper. He worked at Boeing in Seattle for a time, served in the Marines during World War II, loved taking physical risks, and was the right age. Eventually, however, the FBI pressed him hard enough that he admitted being in Nepal in November 1971, and he was ruled out.

Robert Rackstraw was a retired pilot and Army veteran who had a history of run-ins with the law for outlandishly staged crimes. He was arrested in Iran for possessing explosives, he tried to fake his own death by jumping out of a plane over California and was later arrested for forging federal pilot certificates. Despite a slight resemblance to the Cooper FBI sketch, one of the flight attendants said he didn’t look anything like her memory of Dan Cooper, and no direct evidence could be tied to his involvement.

And speaking of Dan Cooper, one of the FBI agents investigating the case discovered a link that may have had some credibility. There was a French-language comic book from Belgium at the time with a character named Dan Cooper, who was a fighter pilot in the Royal Canadian Air Force. While the comic was popular overseas, it had never been translated into English. Though both flight attendants reported that Cooper had no discernable accent, he did use the phrase “negotiable American currency,” in his demand, leading some to believe that he was not necessarily from the United States. Someone from America likely wouldn’t use that phrase. Further, the Dan Cooper character is a test pilot who took part in numerous skydiving adventures. All this circumstantial evidence leads some to believe that the real Dan Cooper is someone who served in the military somewhere in Europe during the years leading up to the skyjacking.

As I said, there are hundreds of similar stories of the FBI investigating and eliminating potential suspects. Do a quick internet search to find out more about who these people are and decide for yourself if there is enough evidence to convince you of D.B. Cooper’s real identity.

More questions than answers

So, what happened to Dan Cooper after he jumped out of the plane that cold, November evening? Did he survive the fall? If so, was he injured and possibly killed by exposure to the elements? If so, where is his body? The briefcase bomb? The parachute? The bank bag? If he survived and landed safely, how did he get out of the forest in the middle of a frozen, rain-soaked night? If he made it out, where did he go to recover from his ordeal?

And perhaps most importantly, where could he have spent any of the money that would have gone completely undetected? After all, to this day, none of the stolen money has ever reentered the American currency system.

These critical facts have led the FBI to speculate strongly that Cooper did not survive the jump. They originally thought Cooper was an experienced jumper, perhaps even a paratrooper, but concluded after a few years this was simply not true. No experienced parachutist would have jumped in the pitch-black night, in the rain, with a 172-mph wind in his face wearing loafers and a trench coat. It was simply too risky.

One of the investigating agents said diving into the wilderness without a plan, without the right equipment, in such terrible conditions…he probably never even got his chute open. Even if he did land safely, agents contended that survival in the mountainous terrain at the onset of winter would have been all but impossible without an accomplice at a predetermined landing point. This would have required a precisely timed jump—necessitating, in turn, cooperation from the flight crew. There is no evidence that Cooper requested or received any such help from the crew, nor that he had any clear idea where he was when he jumped into the stormy, overcast darkness.

Some good comes from it

In the aftermath of the D.B. Cooper heist, there were several changes made to aviation security in the United States. To begin with, after Cooper’s apparently successful skyjacking, the Federal Aviation Administration ordered that by the following year, all airline passengers would have their carry-on items searched and be required to pass through a metal detector before boarding. Cockpit doors were retrofitted with peepholes that allowed the flight crew to see into the cabin without the risk of a passenger storming the cockpit.

The year after Cooper’s caper, there were several “copycat” hijackings, prompting the FAA to require Boeing install a device that prevented the rear staircase of all 727s from being opened from the inside during flight. The device—a small metal spring-loaded latch held in place by high airspeed that releases when the plane isn’t moving on the ground—is known as a Cooper vane because its creation was inspired by the man himself.

Finally, on July 8, 2016, the FBI announced that it was suspending active investigation of the Cooper case, citing a need to focus its investigative resources and manpower on issues of higher and more urgent priority. Local field offices will continue to accept any legitimate physical evidence related specifically to the parachutes or to the ransom money that may emerge in the future. The 66-volume case file compiled over the 45-year course of the investigation will be preserved for historical purposes at FBI headquarters in Washington, D.C., and on the FBI website. And though all the evidence is open to the public, the crime remains America’s only unsolved case of air piracy in commercial aviation history.

Though his body, his equipment, and the majority of his money was never found, there are places in Washington where you can go to learn more about the daring heist of D.B. Cooper. In 2013, the Washington State History Museum in Tacoma featured an exhibit about the case, which centered around one of the four parachutes given to Cooper on the tarmac in Seattle. He jumped out of the Boeing 727 with one of the NB-8 chutes on his back. The other one remained on board and is now in the collection of the Washington State Historical Society.

The town of Ariel continues its Cooper Days tradition every year on the Saturday after Thanksgiving. Everything I’ve read sounds like it’s a raucous good time, populated with every type of personality from college kids looking for a quirky party to hard-nosed conspiratorial types eager to garner support for their Cooper alien abduction theories.

And while D.B. Cooper has become a cult antihero in American culture, I think it’s important not to elevate him to some kind of Robin Hood or Marvin Heemeyer-type figure. Yes, Cooper was polite, well-mannered, well-dressed, and cordial…but he was also a terrorist, a kidnapper who held scores of people hostage with the threat of ending their lives in a fiery explosion. It can be fun to talk about the details of the case, search for undiscovered evidence, and ruminate over the what-if possibilities. But in the end, it’s very likely that the man known as Dan Cooper got what was coming to him.

Let me know your thoughts on the D.B. Cooper case in the comments below.

That is a very interesting theory, Mike! The acronym fits, but I can’t figure out why a skyjacker would want to leave clues by abbreviating his service branch, rank, and unit. I would think anonymity would be his greatest ally in the years following such a brazen crime.

I have a new theory that could help.

D.AN.C.O.O.P.E.R. could be an acronym for DA—Department of the Army….NCO— Non Commisioned Officer….OPER—Operations. His Branch, his Rank, and his unit.

Anybody wanna comment on this possibility?

All of the instructors at Fort Benning Airborne School are NCOs or “black hat” sergeants 1st class.

THOUGHTS?