Exploring Maritime Washington

Podcast: Play in new window | Download | Embed

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | RSS | More

I am proud to announce the publication of my new book, Exploring Maritime Washington—a History and Guide. Each of the places covered in its pages has a connection to Washington’s maritime history, whether a popular tourist destination or a hidden gem known only to longtime locals. Exploring Maritime Washington provides visitors with a fun and easy way to enjoy each community while learning about Washington’s nautical history. By visiting and experiencing Washington’s special maritime features—museums, ships, lighthouses, waterfronts and all—the heritage traveler can obtain an authentic understanding of maritime Washington’s diverse history and culture.

This historical travel guidebook seeks to provide Washington residents as well as visitors from near and far a more comprehensive, inclusive picture and understanding of the maritime heritage of Washington. It’s been nearly two years in the making, but thanks to the efforts of my co-author, maritime historian and author Chuck Fowler, and all the good people at The History Press, the book is now available at Amazon, Barnes and Noble, The History Press’s website, and as many gift shops and bookstores as you can find along the Washington state coastline.

In 2019, Congress designated nearly 3,000 miles of Washington’s immense coastline as a National Heritage Area…one of only 55 in the country, but the only one to focus exclusively on maritime history and heritage. National Heritage Areas are places where natural, cultural, and historic resources combine to form a cohesive, nationally important landscape. They are locally run and completely non-regulatory. NHAs can support historic preservation, economic development, natural resource conservation, recreation, heritage tourism, and educational projects.

And why shouldn’t it be a special heritage area? Within Washington’s protected waterways, you can find a treasure trove of seafaring stories beginning with this area’s original inhabitants, through the period of European-American exploration, settlement, growth, and on up to today’s high-tech working waterfronts. The book, Exploring Maritime Washington, is as much authoritative historical narrative as it is indispensable travel guide. It’s divided into five sections: Central Puget Sound, North Puget Sound, South Puget Sound, the Olympic Peninsula and the Columbia River.

While the Maritime Washington National Heritage Area covers nearly 3,000 miles of Washington’s coastline from the Canadian border down to Grays Harbor County, it doesn’t fully extend into the Columbia River—and there’s a good reason for that. While stakeholders were planning the Maritime Washington National Heritage Area, Columbia River counties in Washington and Oregon were strategizing on creating a heritage area of their own; the Columbia-Pacific National Heritage Area. These efforts unfolded simultaneously, until plans for the Columbia-Pacific Area met resistance and were unable to move forward, ultimately leaving Washington’s Pacific County out of the Maritime Washington National Heritage Area. My book, however, does include Pacific, Wahkiakum, Cowlitz and Clark Counties…basically as far upriver as tidal activity is still measurable.

The five sections in the book each contain Hub Cities from which maritime explorers may choose to venture out to other destinations, like spokes extending from the hub of a wheel. I’m going to tell you some of my favorite stories from each section, beginning with the Central Puget Sound, which includes destinations such as the Museum of History and Industry, the Duwamish Longhouse and Cultural Center, Mukilteo Lighthouse Park, Puget Sound Naval Shipyard, the Poulsbo Maritime Museum, and many more.

Central Puget Sound

Historic Ship’s Wharf at the south end of Lake Union is just outside the Museum of History and Industry. It is perhaps the best place in the state to see a collection of iconic maritime vessels of significance to Washington’s past. Visitors can stroll along the wharf reading about the histories of these ships, taking photographs and even touring them. In the first slip is one of the last remaining Mosquito Fleet ships, the steamer, Virginia V (five), a National Historic Landmark. The only other surviving Mosquito Fleet vessel is the Carlisle II which still plies the waters around Bremerton. Virginia V is sometimes known as “Virginia Vee” or simply “V” to the remaining few who experienced the ship in its heyday. It’s a century-old ship that began servicing the Seattle-Tacoma route in 1922, ferrying thousands of passengers across Puget Sound until 1942.

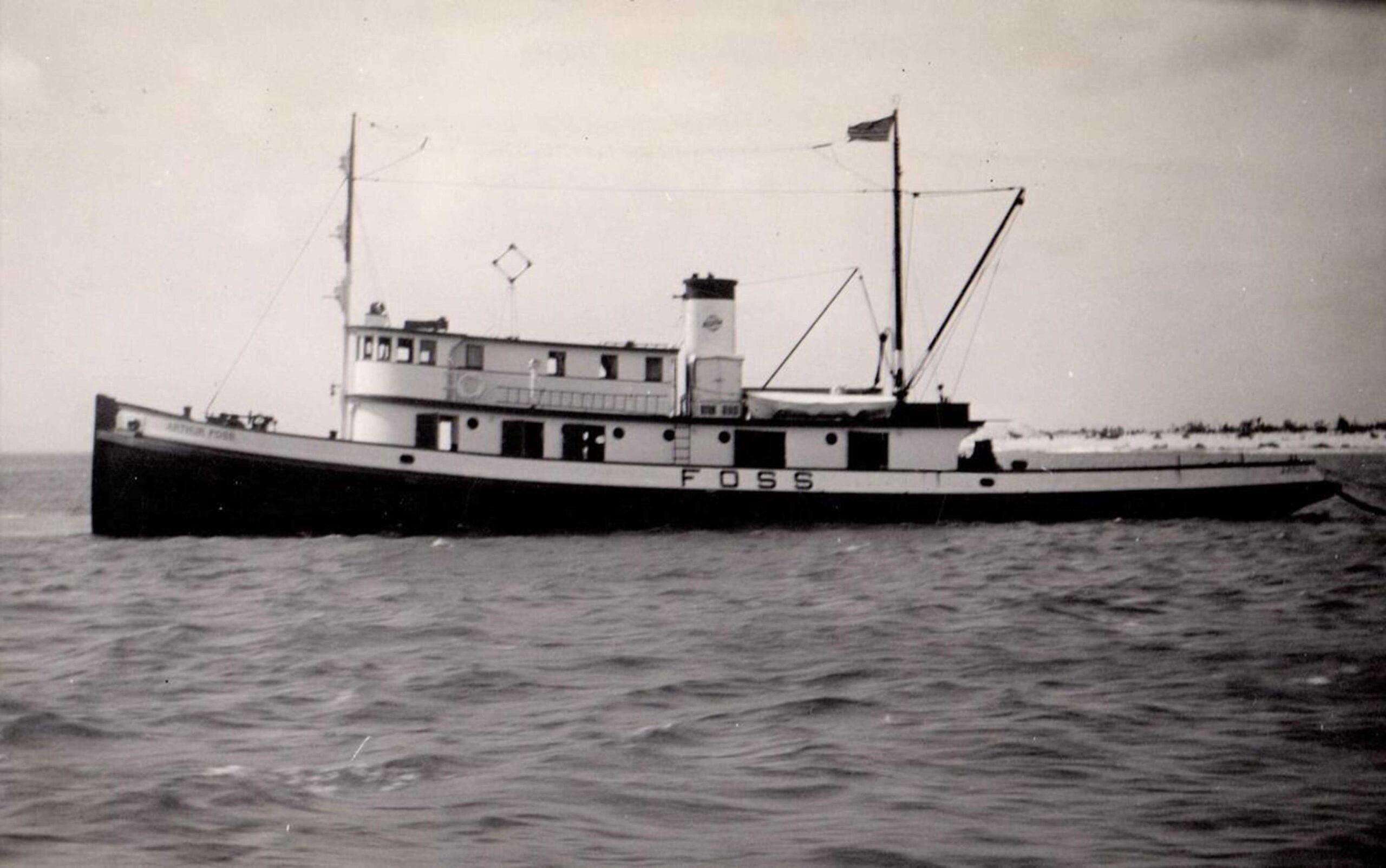

Floating right beside Virginia V is the tugboat, Arthur Foss, more than 30 years older than its Mosquito Fleet neighbor. In fact, it’s the oldest vessel still afloat in the Pacific Northwest. Built in 1889, the same year Washington received statehood, Arthur Foss is one of the founding members of a vast fleet of tugs built by the Foss Launch and Tug Company (known today as Foss Maritime). At one time, its job was to shepherd sailing vessels across the treacherous Columbia River Bar into Astoria. During the Klondike Gold Rush, Arthur Foss towed barges to and from the gold fields in Alaska, and in 1933 it was featured in the film Tugboat Annie, based loosely on the life of Tacoma businesswoman Thea Foss, the company’s founder and namesake. It also has the dubious distinction of being the last ship to leave Wake Island before the Japanese invaded in 1941.

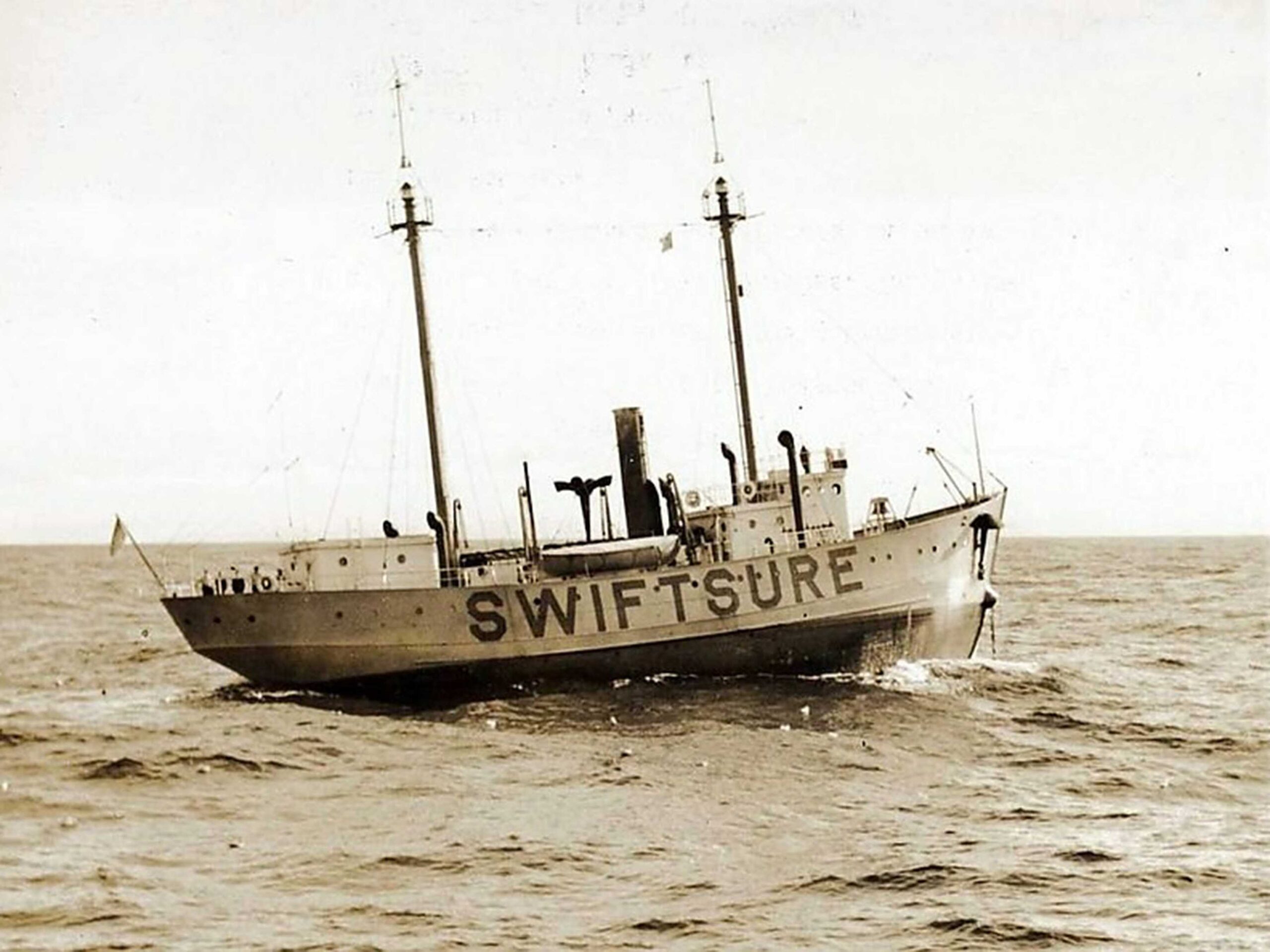

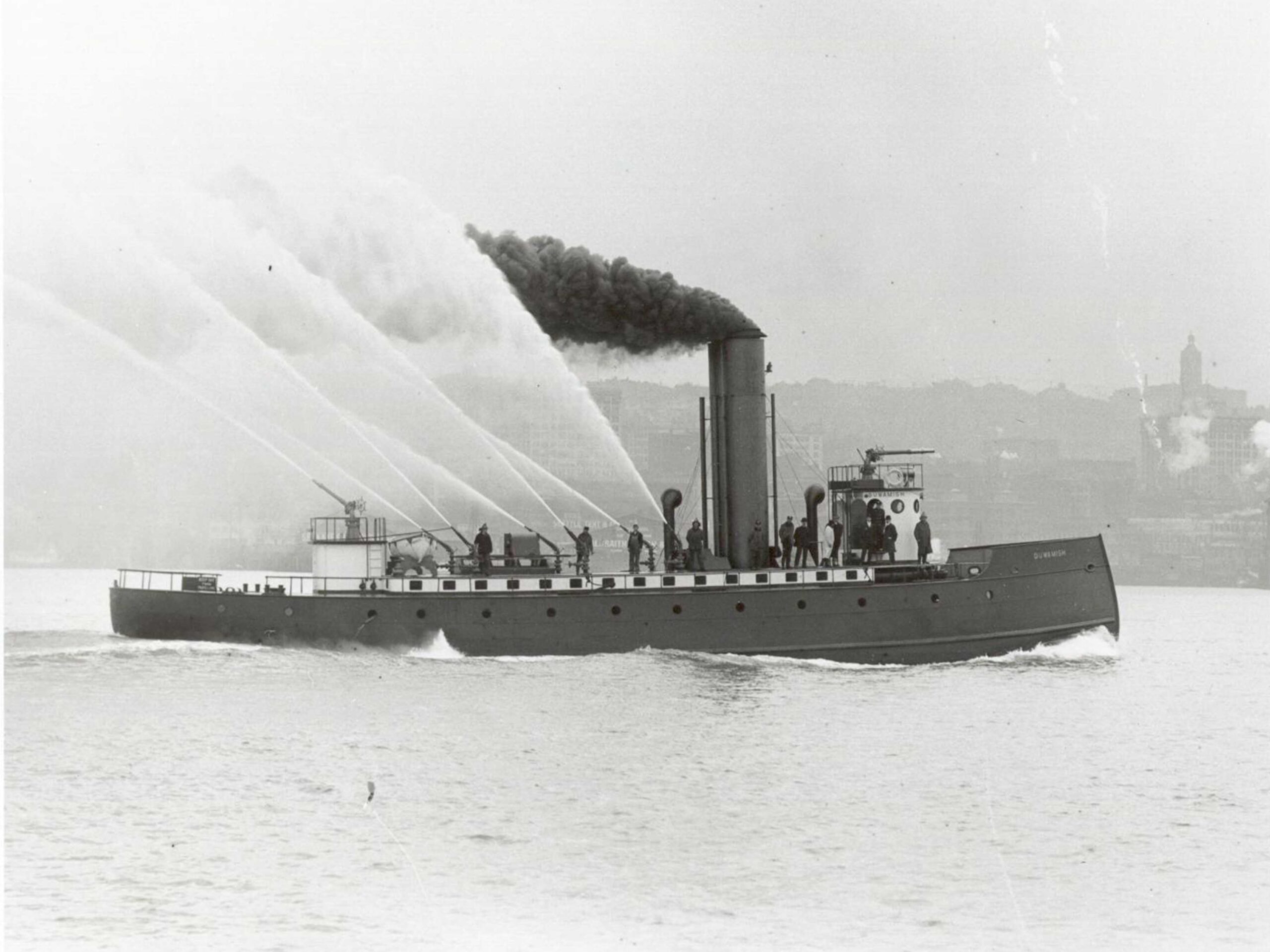

Next in the lineup are two unique service vessels that each played a part in the history of western Washington—the Fireboat Duwamish, which protected Seattle’s wooden waterfront from 1909 until 1985, and Lightship No. 83 Swiftsure, a floating beacon to help guide maritime vessels where no lighthouses could be built. For 94 years, Duwamish was the world’s most powerful fireboat, able to pump 22,800 gallons of water per minute through its nozzles. Just four years after it launched, Duwamish was integral in fighting the Grand Trunk Pacific dock fire on the Seattle waterfront, which leveled the structure in just two hours.

Swiftsure, one of the more unique ships to behold, is the oldest of its kind in the United States. Launched in 1904, Lightship No. 83 (as it’s officially known) protected sailors up and down the Pacific Coast until 1960, and still retains its original steam engine. Lightships were traditionally named after the station to which they were assigned but were given numerical identifiers in 1867 to make recordkeeping easier. Swiftsure’s last point of service was off the Swiftsure Bank in the Strait of Juan de Fuca between Washington and Vancouver Island, Canada. During its period of service, Swiftsure helped rescue hundreds of people from dozens of stranded and sinking ships. Both Duwamish and Swiftsure are official Seattle Landmarks as well as National Historic Landmarks.

Rounding out this cast of characters moored at Historic Ship’s Wharf is the schooner Tordenskjold. Built in 1911 in Seattle’s Ballard neighborhood, it spent over a century fishing the North Pacific for halibut, cod, tuna, crab, shrimp and more. Tordenskjold – affectionately called “Tordie”—retired from service in 2012 and was donated to Northwest Seaport five years later. Historic Ship’s Wharf is just a stone’s throw from the Museum of History and Industry in Seattle and the Center for Wooden Boats at the south end of Lake Union.

North Puget Sound

One of my favorite destinations in the North Puget Sound region, which includes Whatcom, Skagit, Island and San Juan Counties, and the Hub Cities of Bellingham, Anacortes, Coupeville and Friday Harbor, is the Maritime Heritage Center in Anacortes. Visitors can experience the town’s rich waterfront history through exhibits and artifacts related to indigenous life in the area, early exploration, the fishing and cannery industries, ship building, ferries and the Port of Anacortes’ history, lumber mill operations and recreational boating in the 20th Century. Vintage movies and mural-sized photographs from along the waterfront supplement the displays, along with the six-foot wooden wheel and telegraph from the historic ferry Vashon. The exhibits provide a complete overview of shoreline activities, including boat building, mills and canneries, commercial and recreational boating, shipping and transportation.

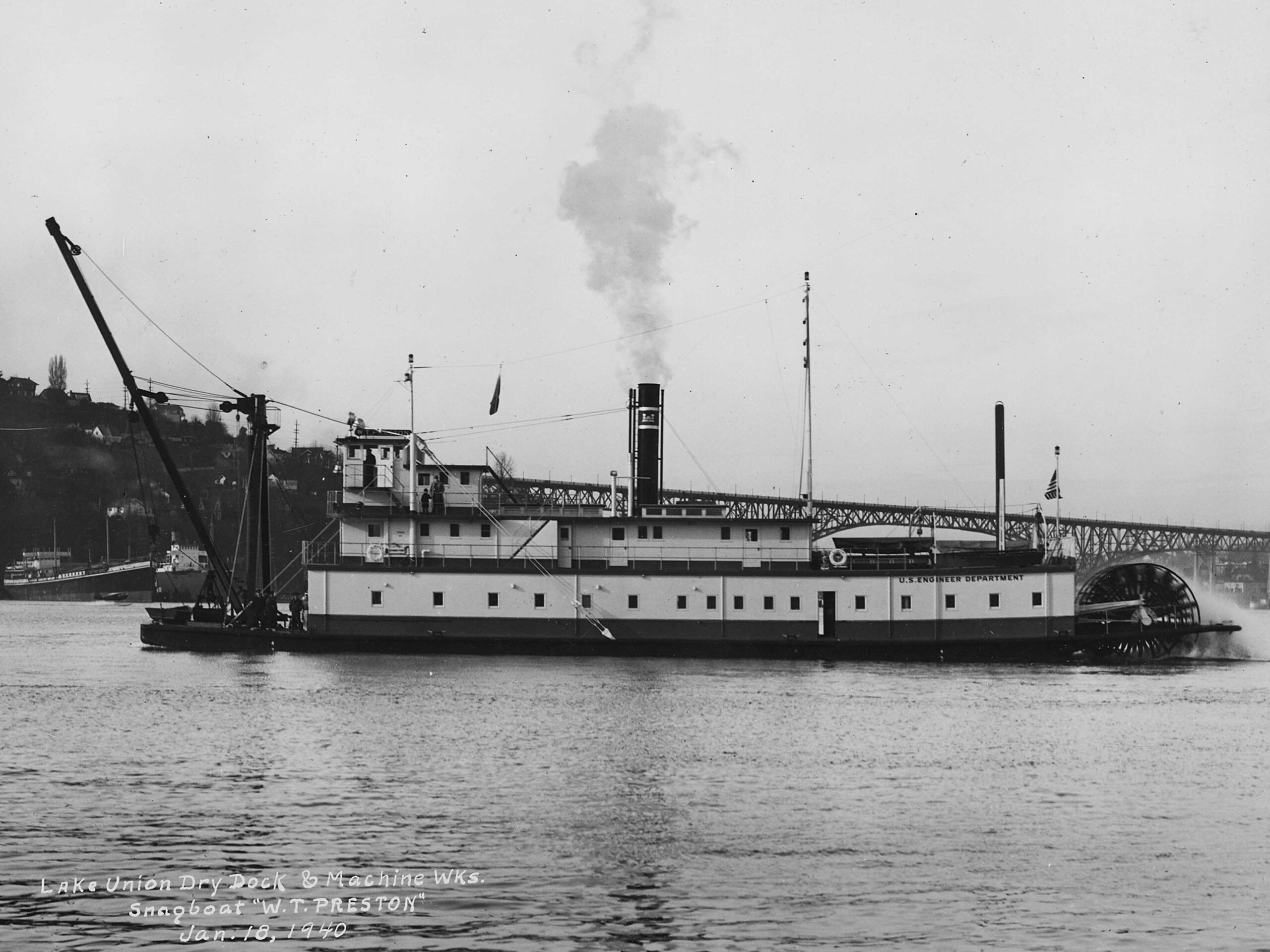

However, dominating the entryway to the center is the enormous sternwheel steamer, W.T. Preston, one third of a trio that once kept the area’s inland waterways navigable. Now a National Historic Landmark, the W.T. Preston’s job from 1929 through 1981 was to remove navigational hazards from the bays and harbors of Puget Sound and the rivers feeding it. Fallen trees and other debris could create logjams and shifting sand bars made river travel treacherous. The W.T. Preston—along with her predecessors, the Skagit (1885-1914) and the Swinomish (1914-1929)—worked from Blaine to Olympia, clearing countless snags, logjams and other debris, including numerous sunken marine vessels and even a crashed airplane. Named for a distinguished civilian engineer who worked for the Army Corps of Engineers, the W.T. Preston was also used as a pile driver, an icebreaker and dredged about 3500 cubic yards of material in an average year.

When the cost to maintain the W.T. Preston became prohibitive, the Army Corps of Engineers finally retired the storied steamer and sought for it a permanent home. The City of Anacortes was an excellent choice, given how much time the snagboat had spent in nearby waterways. In 1983, the W.T. Preston was hauled out of the water for the last time and moved to its current location, where it educates throngs of visitors annually about maritime history in Washington. Admission to the maritime heritage center is free, and tours of the snagboat conducted by an extremely knowledgeable volunteer docent are only $5.

Other notable destinations in the North Puget Sound region include Salmon Woman at Maritime Heritage Park, Ship Harbor Interpretive Preserve, the Langley Whale Center, Fort Casey, Roche Harbor, and more.

South Puget Sound

The South Sound region is made up of Pierce, Thurston and Mason Counties and includes the Hub Cities of Tacoma, Olympia and Shelton. Some of the destinations within the South Puget Sound section include Gig Harbor’s historic net sheds, the Steilacoom Tribal Museum, Olympia’s historic waterfront, the Billy Frank Junior Nisqually National Wildlife Refuge, the Squaxin Island Tribal Museum, and more. There is also a hidden gem that shouldn’t be missed if you enjoy hiking as well as maritime history. However, it must be undertaken at low tide, as it leads to a unique shipwreck just off DuPont’s coast. Known locally as the Concrete Ship or the Cement Ship, the hundred-foot hulk all but disappears when the tide is in but lies split in two and half buried in the tide flats when the water is at its lowest. Originally built as a water tender in 1919 by the Great Northern Shipbuilding Company out of Vancouver, Washington, ship number 223169 was given the name Captain Barker. Along with its four sister ships, these five “stone boats” were to be towed to Fort Stevens, Oregon, and San Francisco, California, by the U.S. Army tug Slocum…until three of them were lost en route during a nasty storm.

Only the Captain Barker and the Captain Bootes survived the journey, and both were later sold to the Foss Launch and Tug Company in the 1950s and renamed Foss 103 and Foss 102, respectively. Records don’t reveal what happened to the Captain Bootes, but the Captain Barker appears to have been lost sometime in the 1970s, sinking to the ocean floor in the very spot it remains today. These types of ships are constructed with reinforced steel bars encased in concrete due to the lower cost of materials (at the time) compared to more traditional methods. Known as ferrocement ships, they were used heavily between WWI and WWII and helped support both United States and British invasions in Europe and the Pacific.

Maritime explorers can park at the DuPont Civic Center, 1700 Civic Drive, and hike the nearly two-mile Sequalitchew Creek Trail to the beach. Turning left and hiking along the waterfront for another 30 minutes or so should bring the wreck into view. At a minus tide, the straight path from the beach to the boat is clearly visible and the wreck is completely exposed, just waiting for exploration. Adventurers should be warned, however, not to spend too much time pondering the past, lest the tide come in and trap them aboard the derelict vessel for about another 12 hours.

Olympic Peninsula

Over to the Olympic Peninsula now, which includes the counties of Jefferson, Clallam and Grays Harbor, and the Hub Cities of Port Townsend, Port Angeles, Neah Bay and Aberdeen. Some of the destinations in the Olympic Peninsula Section include Forts Worden and Flagler, the Feiro Marine Life Center, the Makah Cultural and Research Center Museum, and the recently remodeled Coastal Interpretive Center in Ocean Shores.

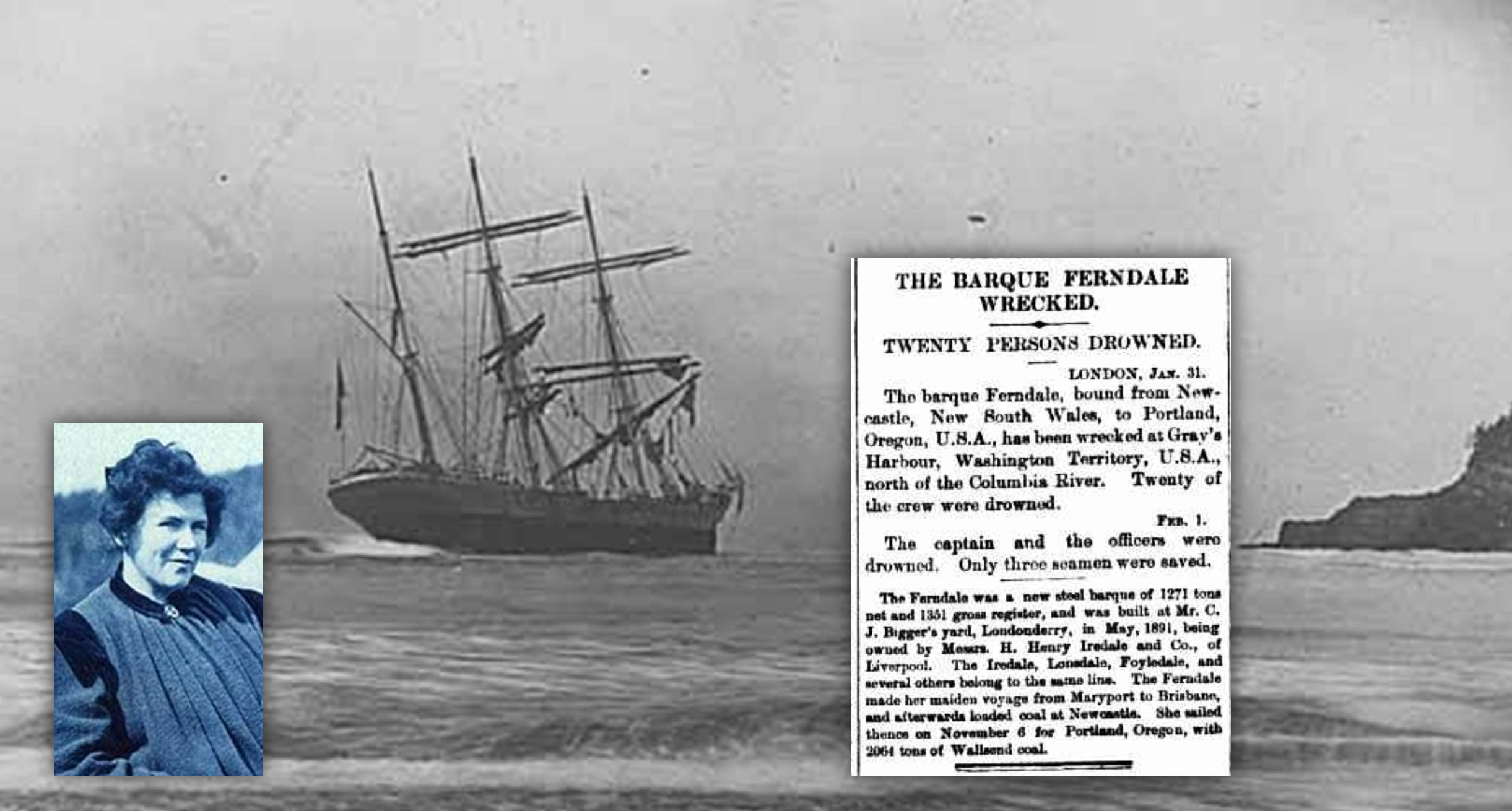

One of my favorite stories from the Pacific Coast is of Martha White and the wreck of the British bark Ferndale in 1892. As many an unfortunate sailor has learned, the underwater topography off Washington’s coast often combines with hazardous weather patterns to generate a swift surface current that drives ships northward. Should a ship awaiting a pilot to escort it safely suddenly be cut loose by severe winds, it very well could meet the same deadly fate as dozens of others over the years. There have been all manner of ships grounded along the North Beach and subsequently destroyed by the pounding of the relentless surf, but perhaps none as dramatically as the Ferndale.

Just after the New Year in 1892, a season notorious for bad maritime weather, the 240-foot sailing vessel was hauling a load of coal and coke from Newcastle, New South Wales, Australia, to Portland, Oregon, when it got caught in a heavy current trying to enter the Columbia River. In a deep fog, despite having its anchors out, the gale force winds blowing from the southwest drove the ship some 60 miles to the north and ran it hard into the sands near Copalis just after 3:00 a.m. As the ship listed severely to one side, the waves began smashing over the deck and washing away anything that wasn’t tied down. Some crewmen grabbed life vests while others lashed themselves to the masts or the rigging. An unfortunate few were simply washed overboard and vanished beneath the pounding surf.

After four relentless hours, the first shades of daylight began illuminating the nearby beach and neighbors along the coast spotted the ship in distress. They notified homesteaders Edward and Martha White, who quickly dressed and made their way down to the beach to help. While Edward headed north searching for survivors, Martha waved a white flag from shore and fired a pistol to get the attention of any crewmen still aboard the Ferndale. Around the same time, three sailors still aboard—seeing the futility of their situation—decided to untie themselves and swim for shore. Exhausted and frozen, Erick Sundberg, Charles Carlson and Peter Patterson leapt into the icy breakers and prayed for a miracle.

Barely conscious, Sundberg found his miracle when the 25-year-old Martha spotted him being tossed about like a ragdoll in the surf. She waded in, removed his waterlogged life preserver and dragged him up the beach to her house. Returning a few minutes later, she found Carlson unconscious in the sand and dragged him to safety as well. As she ran back to the water’s edge, Martha saw Patterson caught in the waves just offshore. Like a scene from an action movie, Martha tore away part of her soaked skirt material and dove in to rescue him. By the time she was able to pull him from the water, they both had reached their physical limit and collapsed onto the beach. Edward gathered several neighbors to bring the remaining survivor inside to recover, but 20 or so crewmen did not survive the ordeal. The bodies of five others washed ashore in the following days and were buried nearby.

Word began to spread of Martha’s heroism, aided by testimony from the surviving sailors, and soon newspapers across the world had picked up and reprinted the story. State and federal politicians representing the area quickly petitioned the Treasury Department’s Life-Saving Service to bestow upon Martha a Gold Lifesaving Medal, which she received that July. The citizens of Portland, Oregon (where the cargo was destined), also honored Martha’s efforts with a gold medal along with a cash reward. Travelers exploring Washington’s North Beach today can still sometimes find chunks of coal from the Ferndale washed up after a storm. Those who don’t can always visit the Museum of the North Beach in Moclips to see some for themselves.

Columbia River

The final section of my book encompasses four counties not included in the Maritime Washington National Heritage area, but whose contributions to Washington’s nautical narrative ought not to be overlooked. We’re talking about Pacific, Wahkiakum, Cowlitz and Clark Counties, and the Hub Cities of Raymond, Ilwaco, Longview and Vancouver. Some of the destinations in this section include the Willapa Seaport Museum, the Lewis and Clark Interpretive Center, Kalama’s Transportation Interpretive Center, the Fort Vancouver National Historic Site, and many more.

Located a short drive south of the Fort Vancouver area is an industrial waterfront that would ordinarily not attract even the least bit of attention. Visitors looking in the right place, however, will find something remarkable that is arguably underappreciated in Vancouver’s maritime history. South of Highway 14 (the Lewis and Clark Highway), at the end of SE Marine Park Way, is the Henry J. Kaiser Memorial Shipyards observation tower. The three-story triangular platform is adorned with numerous interpretive panels telling the story of how one man and an unshakable labor force helped the U.S. win WWII.

In 1942, industrialist Henry Kaiser came to Vancouver and obtained 200 acres of riverfront land to build a shipyard that supplied America with ships for the war effort in the Pacific. Between then and 1946, the Kaiser Shipyard was the nation’s most versatile, churning out 141 vessels of 5 different types—nearly one a week during its operation. Included in the final tally were 10 liberty ships, 30 tank-landing ships, 50 escort aircraft carriers (known as “baby flattops,” they could carry and launch 37 planes each), 31 troop transports and 8 cargo ships among others. These ships launched from one of 12 bays that released vessels to the waiting river on rail lines.

Running these shipyards were tens of thousands of men and women who served as welders, shipwrights, painters, riveters, shipfitters, machinists, electricians, crane operators and more. They had come by invitation from Kaiser himself, who recruited across the country with promises of good pay, housing and medical care (ever hear of Kaiser Permanente health insurance? Yep, that started here too!). The biggest crowd Vancouver had ever seen in one place gathered on April 5, 1943, when Eleanor Roosevelt christened one of the shipyard’s latest creations. Eyewitnesses estimate around 75,000 workers, residents and guests turned out to greet the First Lady as she smashed a bottle of champagne across the bow of the USS Alazon Bay, later renamed the USS Casablanca.

Exploring the area today, visitors might have a challenging time spotting the shipways through the trees that have grown over the years. Study the photographs in the panels affixed to the tower, then look harder at the industrial site across the public boat launch, and the outlines of concrete walls and ramps disappearing into the river can be seen through the undergrowth. While the sight of aircraft carriers lined up on the Vancouver waterfront may never be seen again, there are still remnants of that monumental effort visible to explorers who look in just the right places today.

Keep exploring

It would be impossible to fit the entirety of Washington’s maritime history into a book of this size. There are far too many fascinating stories, culturally significant destinations and critical background points to tell the complete nautical narrative of this great state. With each successive interview of a local historical expert or visit to a harbor or coastal community, it soon became clear that I would have to winnow the topics to focus on the truly unique or the most hidden gems. Even that presented challenges, as I felt compelled to honor the passions of each dedicated museum volunteer, historical society board member, tribal cultural resource officer and destination marketing representative who permitted me an interview or assisted with research. Ultimately, I included as much of the best material as I could—but in no way does it represent the totality of the always fascinating, sometimes terrifying, often inspiring and even humorous history that comprises the raw material with which the community of Washington was built. This book represents the shared maritime history of so many people who deserve adulation for their own research, collections and dedication to preservation.

The uniqueness of Exploring Maritime Washington is based on providing the history enthusiast and travelers a hands-on guide to the state’s myriad cross-cultural attractions, sites and stories. By visiting and experiencing Washington’s special maritime features—museums, ships, lighthouses, waterfronts and all—the heritage traveler can obtain an authentic understanding of maritime Washington’s diverse, inclusive history and culture. This historical guidebook, prepared by lifelong residents who are also knowledgeable historians and seasoned travelers, offers insider information, hidden gems and special stories that make Washington’s maritime history truly extraordinary. On behalf of Chuck, former Secretary of State and longtime heritage champion Ralph Munro who wrote our foreword, and me…we hope you enjoy using it to explore and discover maritime Washington.