The 1910 Wellington Train Disaster

Podcast: Play in new window | Download | Embed

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | RSS | More

Just after one o’clock in the morning, on a frigid, starless night in March 1910, more than a hundred souls aboard Great Northern Railway’s Spokane Local No. 25, a passenger train, and Fast Mail Train No. 27 slept tightly bundled in their cars. They’d been stuck near Wellington in King County, Washington, for almost a week…waiting as railroad crews attempted to clear the tracks of snow, which had been accumulating at a record pace. Each time they tried, their enormous rotary plows either broke down, ran out of fuel or got stuck, forcing crews to try digging out from the five-to-eight-foot snow drifts by hand while passengers hunkered down and waited for the blizzard to pass.

But it didn’t pass. The snow just kept on coming. High above them loomed the peak of Windy Mountain, and below them, the Tye Creek ravine. On the last day of February, the snow turned to rain. Lightning and thunder erupted across the Cascade Mountains, and one fateful lightning strike touched off the deadliest avalanche in United States history.

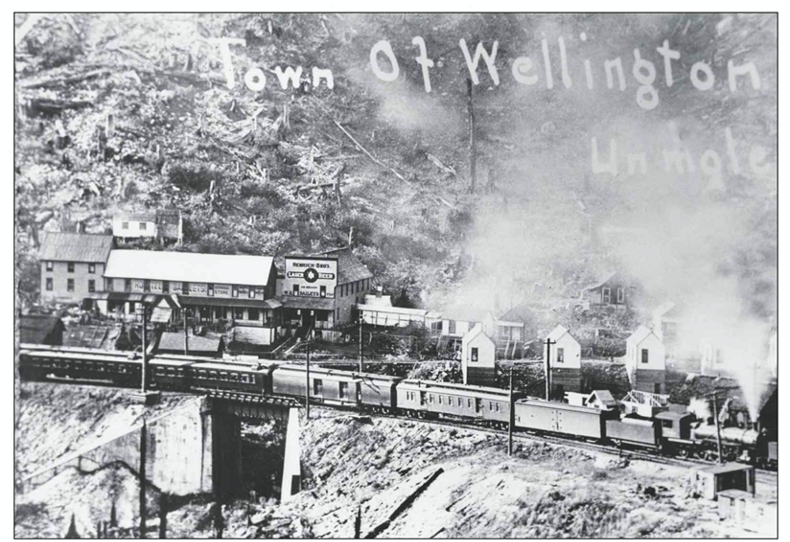

So where exactly is Wellington, Washington? If you guessed somewhere near Burlington, Arlington, and Darrington, you’d be in the right general vicinity. But if you’re looking for it on a map, you might have a tough time finding it. Its name was changed after the tragedy and the town itself was eventually abandoned and burned to the ground in the following years. Heading east from Everett on US Highway 2, travelers will pass through the towns of Monroe, Sultan, Startup, Gold Bar, Index, Skykomish, and Scenic before reaching the summit of Stevens Pass high in the Central Cascade Mountains. Heritage adventurers just might be interested in taking a short detour to hike along the 6-mile Iron Goat Trail, so named because the Great Northern railroad that used to travel along the route featured a stoic mountain goat in the company’s logo. It’s a fantastic hike with only about 700 feet of elevation gain from beginning to end. If you want to learn more about the trail, its history and some great tips and tricks to make your hike unforgettable, go pick up a copy of the book, Day Hiking Central Cascades, by my friend Craig Romano.

At the summit of Stevens Pass is the fabled ski area to the south. On the north side of Highway 2, however, is a nondescript gravel path called Tye Road that would likely be overlooked by travelers passing at freeway speeds. But turning on to this road and looking up into the trees will reveal handmade signs directing visitors to the Wellington trailhead just a little over three miles or 15 minutes away.

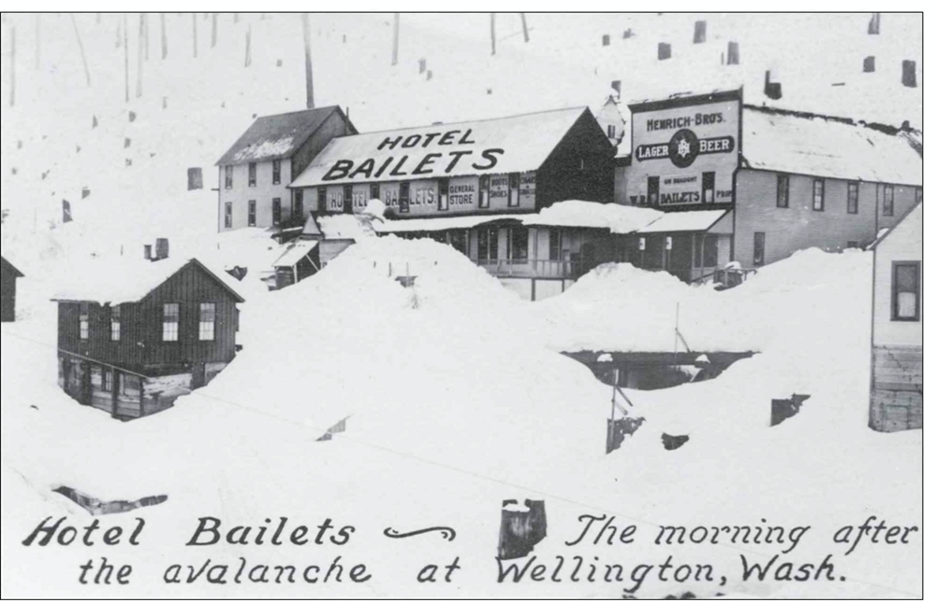

The Iron Goat Trailhead provides explorers with ample parking spaces, interpretive signage, and relatively clean pit toilets. Hikers have two options from here, but turning left will lead to the original Cascade Tunnel—a short, dead-end trail with a number of historical panels that help visitors understand the context of life in a railroad town in the early 1900s. Wellington was once a vital coal, water and rest stop for trains heading through the mountains and was the only town for miles where workers could purchase supplies from the Henrich Brothers’ general store and gather overnight at the Hotel Bailets. Visitors today can still find remnants of that long-forgotten lifestyle along the trail…if they look in just the right places. For example, standing atop the ledge looking down into Tye Creek (also known as Tye River), eagle-eyed adventurers can spot an old, rusty railroad tie sticking out of the side of the hill.

Along the trail, explorers will also find the footing of Great Northern’s coal tower, built in 1910. It’s an enormous cement foundation that once supported the lifeblood of the railroad industry. Workers would load coal into the bottom, and a conveyor would raise it up to the hopper where it would await the next locomotive to park beneath it. Locomotives would consume about a ton and a half of coal while winding their way through the switchbacks before the Cascade Tunnel was completed.

Farther up the trail lies the remains of the 200-foot-long railroad inspection shed and rotary plow storage building. Trains were driven into the shed along two rails but between the rails was a deep pit where workers could inspect and repair the underside of the locomotive (a lot like Jiffy Lube or Oil Can Henry’s today). Though the structures are long gone, and the pit has been filled with earth over time, you can still make out the width of the area and see the right-angled concrete edges where the rails would have carried train cars into the shed.

A few more feet down the trail, hikers will be met with a couple more signs and a warning not to go any further. It’s from this vantage point that you can actually see the remains of the original Cascade Tunnel through the trees and bushes. If you go a little further, I’m told…and you’re not supposed to do this, so consider yourself warned…there are more concrete building foundations now hidden by the undergrowth. Just past these is the tunnel itself, once a vital link between east and west, a proud monument to human ingenuity and determination, now decorated with graffiti and left to slowly crumble away. The old Cascade Tunnel was abandoned in 1929, after the new tunnel opened at a lower elevation. The old tunnel was a popular hiking and exploring destination until the winter of 2007–2008, when a section of the roof caved in and created a debris dam inside the tunnel, making it impassable due to standing water and hazardous ceiling debris. Authorities issued a warning to stay clear of the old tunnel for a distance of half a mile, a regulation that will remain in place for the indeterminate future.

At the end of the tunnel trail, just below the interpretive signs, hikers can still find railroad debris rusting away on the forest floor today…remnants of a busier time in the Central Cascades, and a reminder of the aftermath of the deadliest avalanche in US history.

Now, if you recognize that the avalanche happened where the trains were parked just outside the old tunnel, you’re probably wondering why the engineers didn’t just back the train into the tunnel and wait out the blizzard in there. Well, there’s a reason for that. On more than one occasion in history, trains passing from one end of a tunnel to another actually had passengers suffocate. In 1944, for example, a stalled train inside a tunnel near Balvano in southern Italy killed 520 people due to carbon monoxide gas from the steam engines of the locomotive. In 1910, trains were constantly belching out smoke, and steam, and other noxious fumes, and the passengers knew of the danger. They didn’t want to be caught in that situation, so they opted to take their chances outside the tunnel. They had no idea that they were going to be directly in the path of the avalanche.

Once you’ve taken in your fill viewing the western end of the old Cascade Tunnel, go ahead and backtrack to the trailhead and turn right. You’ll be heading toward the all-concrete snowshed, built the year following the disaster to hopefully prevent anything like it in the future. On the way, hikers will pass the runaway track grade, which was used to slow and stop trains coming from the tunnel and moving through town with defective or weak breaks. The original runaway track was destroyed by the 1910 avalanche.

Shortly after the runaway track sign is the entrance to the concrete snowshed, a massive buttress unlike anything else found in Washington. And since the Iron Goat Trail runs along the rail bed where the trains once traveled, hikers are led directly into the storied structure to learn more about the disaster caused by the deadliest avalanche in American history. For protection at the site of the 1910 avalanche, the Great Northern built a 2,463-foot long, double-track snow shed. It’s nearly half a mile long. Now due to the high cost of its construction, this was the only all-concrete snowshed the Great Northern ever built. The entrance to the snowshed marks the approximate location of the eastern extent of the 1910 avalanche.

When the lightning bolt struck the summit of Windy Mountain, a wall of ice and snow 10-feet high, a half-mile long and a quarter mile wide began to careen down the mountain, unimpeded by brush and undergrowth thanks to logging and wildfires that had swept through the area the previous summer. A Great Northern employee named Charles Andrews heard the sound as he was walking toward one of the nearby bunkhouses. As he turned, he saw:

“White death moving down the mountainside above the trains. Relentlessly it advanced, exploding, roaring, rumbling, grinding, snapping—a crescendo of sound that might have been the crashing of ten thousand freight trains.”

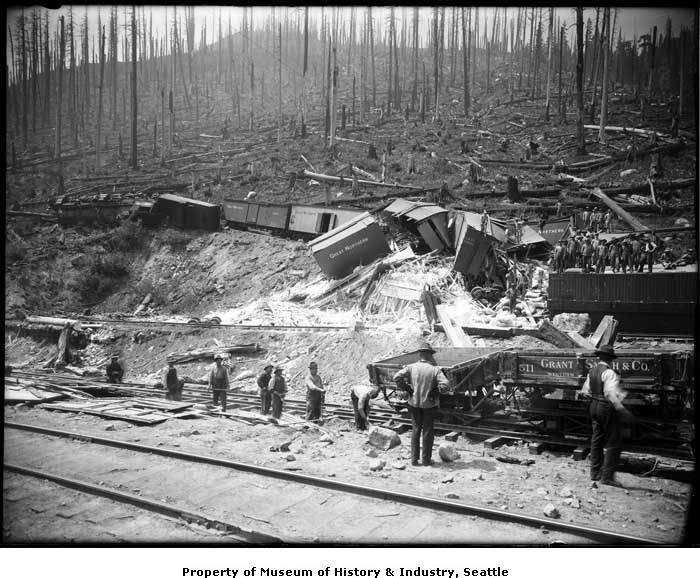

Andrews recalled witnessing the avalanche lift the two trains clean off the rails and throw them effortlessly into the air, where they disappeared into the spray of snow and debris. One survivor said it swallowed them “like a white, broad monster.” Five or six steam and electric engines, hauling 15 boxcars, passenger cars and sleepers. The train cars plunged 150 feet down into the ravine, rolling and tossing, smashing through trees and boulders, some of which were big enough to split the cars in two before they disintegrated at the bottom. By the time the avalanche finally came to rest in Tye Creek, the remains of the Spokane Local and Fast Mail trains were buried under 40 feet of snow.

When the avalanche slammed into the two trains, it only narrowly missed the town of Wellington itself. Remember, it was a little past one in the morning when the disaster struck. Awakened by the cacophony, patrons at the Hotel Bailets and nearby single-room cabins rushed out into the wind and sleet to see what had just happened and were stunned to find both trains had vanished. Clamoring down the mountainside in their nightclothes, they began frantically searching for survivors amidst the debris. However, the worsening weather forced them to suspend their rescue efforts until conditions improved.

In the following days, word spread to nearby towns and more volunteers arrived to assist, including famed Northwest photographer Asahel Curtis. Newspapers began sensationally referring to the area as “Death Hill.” In all, 23 survivors were pulled alive from the mangled wreckage, describing scenes of horror as they were tossed around inside the tumbling train cars. Only one of the nine crewmen on the Fast Mail train survived. 19-year-old Alfred Hensel fell asleep on the opposite end of the car from his coworkers. When the avalanche hit, it split their car in half and the other eight men were swept away in the fray.

Those who did not survive were carefully wrapped and placed on toboggans tied together with long ropes to be taken down the mountain for identification and burial. Curtis captured a number of images of volunteers tasked with this somber duty, many of which can be found in the University of Washington’s Special Collections and the Library of Congress. Recovery crews dragged the bodies for miles until they could be hoisted down a slope to the nearby town of Scenic. The gruesome task included tying a rope to the victims’ feet, then lowering the bodies headfirst, before reaching the recovery train.

In all, 96 people were killed (although some including 35 passengers, 58 Great Northern employees on the trains, and three railroad employees sleeping in cabins. Some were killed instantly from blunt force trauma. Others suffocated in the densely packed snow. It took the Great Northern three weeks to repair the tracks before trains started running again over Stevens Pass. In fact, the snow was so dense it took rescue crews 21 weeks before the last of the bodies was retrieved in late July.

Great Northern soon invested millions to build this snowshed at the disaster site, hoping to spare lives in future avalanches. Wellington was soon renamed Tye by the Great Northern, after the creek that ran nearby, in the hopes of removing any negative associations with the area…but it wasn’t enough to save the community. The New Cascade Tunnel opened in 1929, bypassing Wellington altogether…and the town soon ceased to exist.

As you walk through the snowsheds on the Iron Goat Trail, you can imagine the Great Northern trains coming through, which they did until the new tunnel opened in 1929. Today, all that remains rusted bits of metal scattered about the forest floor, crumbling concrete, rotting railroad ties, and the collapsed Cascade Tunnel at the site of America’s deadliest avalanche.

What will forever remain are the names and stories of those who lost their lives here…a sorrowful list compiled quite reverently by Seattle’s Queen Anne Historical Society, that I’m going to share with you now. These are the passengers aboard Spokane Local Number 25:

- Richard Barnhart, a 40-year-old attorney from Spokane who left behind his wife and small child.

- 40-year-old George Beck, his 30-year-old wife, Ella, and their three children, Harriet (age 6), Erma (age 4), and Leonard (age 2), all from Marcus, Washington, just north of Kettle Falls.

- R. H. Bethel, a 44-year-old contractor and consulting engineer of the Seattle firm Bethel & Downey, who left behind a wife.

- 34-year-old Albert Boles from Moberly in Ontario, Canada.

- John Brockman, a 45-year-old rancher from Waterville, Washington, northwest of Wenatchee.

- H. D. Chantrell, a 50-year-old customs officer at the Canadian border crossing in Blaine, Washington, who left behind a son.

- 60-year-old Alex Chisholm from Rossland, British Columbia, Canada, who left behind his wife.

- 50-year-old Solomon Cohen of Everett, Washington, who was survived by his wife and five children.

- 69-year-old Sarah Jane Covington who left behind her husband and children.

- George Davis, a 35-year-old Seattle motorman on Seattle, Renton & Southern line, and his 3-year-old daughter Thelma.

- Charles Eltinge, the 50-year-old treasurer of Seattle’s Pacific Coast Pipe Company, who was survived by wife and five children.

- 26-year-old George Heron, and his companions 24-year-old John Mackie and 26-year-old James Monroe, Irish immigrants who were all working at a sawmill in Moyie, British Columbia.

- Libby Latsch, the 30-year-old head of Northwestern Sales Company in Seattle who left behind her husband and small child.

- Sam Lee, a 25-year-old tattooed American man about which we do not know more.

- Edgar Lemman, a 47-year-old attorney from Hunters, Washington, on Lake Roosevelt, and his wife, 39-year-old Ada, who left behind their young daughter.

- Nellie Sharp McGirl, a 26-year-old writer survived by her husband in California.

- 59-year-old James McNeney, a Seattle attorney and former judge survived by his wife.

- 55-year-old Albert Mahler, a Seattle real estate dealer who left behind his wife and son.

- Bert Matthews, a 37-year-old traveling salesman from Cincinnati, Ohio.

- William May, a 54-year-old from Chemainus, British Columbia, Canada, who was traveling with his wife, adult daughter and grandchildren who survived. His 9-year-old granddaughter, Lillian, and eight-month-old grandchild, Francis, perished with him.

- Catherine O’Reilly, a 26-year-old nurse from Sacred Heart Hospital in Spokane.

- Benjamin Thompson from Rossland, British Columbia, Canada, who left behind a wife.

- The Reverend James Thomson, a 57-year-old minister from Bellingham who left behind his wife and grown sons.

- Edward Topping, a 29-year-old traveling representative for Safety Door Hanger Company out of Ashland, Ohio, who left behind a small son.

- J. R. Vail, a 60-year-old sheepherder from Trinidad, Washington, on the Columbia River south of Wenatchee.

These are the railroad employees aboard both Spokane Local No. 25 and the Fast Mail Train No. 27:

- Lee Ahern, a 25-year-old mail weigher from Spokane on Train No. 25.

- Grover Begle, a 24-year-old express messenger from Seattle on Train No. 25 who left behind a wife.

- Earl Bennington, a 29-year-old fireman from Kingston, Ontario, Canada.

- John Bjart, a 40-something laborer.

- Arthur Blackburn, a 33-year-old trainmaster survived by his wife and week-old baby in Everett, Washington.

- Richard Bogart, a 36-year-old mail clerk on Train No. 27.

- Fred Bohn, a 20-year-old mail weigher from Palouse, Washington, just north of Pullman on Train No. 27.

- William Bovee, a 26-year-old brakeman from Renton, Washington.

- Alex Campbell, who went by “Ed”, a 28-year-old rotary conductor who died in one of the cabins, leaving behind a wife in Bellingham, Washington.

- J. O. Carroll, an engineer survived by wife in Everett, Washington.

- G. Christy, a laborer with no known kin.

- William Corcoran, a 45-year-old engine watchman.

- William Dorety, spelled d-o-r-e-t-y, a brakeman of unknown age.

- Anthony Dougherty, spelled d-o-u-g-h-e-r-t-y, a 27-year-old brakeman from Waverly, Minnesota.

- H. J. Drehl, a 40-year-old express messenger from West Alexandria, Ohio.

- William Duncan, a 45-year-old porter from Seattle.

- Archie Dupy, a 23-year-old brakeman from Waynoka, Oklahoma.

- Earl Fisher, just 19, who was either a fireman or laborer from Rossland, British Columbia, Canada.

- John Fox, a 42-year-old, mail clerk in charge of Train No. 27, who left behind his wife and three children in Seattle.

- Donald Gilman, a 33-year-old electrician who died in one of the Wellington cabins.

- M. Milton Hicks, a 25-year-old brakeman from Sedro-Woolley, Washington, south of Bellingham.

- George Hoefer, a 28-year-old mail clerk aboard Train No. 27 who left behind his wife in Spokane.

- Benjamin Jarnagan, a 31-year-old engineer from Seattle.

- G. R. Jenks, a fireman from Everett.

- Charles Jennison, a 28-year-old brakeman from Zimmerman, Minnesota.

- Sidney Jones, a 25-year-old fireman from Everett who left behind a wife.

- John Kelly, a 23-year-old brakeman from Everett.

- William Kenzal, a 38-year-old brakeman from Rochester, New York.

- Charles LaDu, a 26-year-old mail clerk from Sidney, New York.

- 25-year-old laborer Gus Leibert and J. Liberati, age unknown.

- Stephen Lindsay, who also went by “Ed”, a 33-year-old rotary conductor from Seattle.

- Earl Longcoy from Wisconsin, the 19-year-old secretary to Great Northern’s Cascade Division Superintendent J. H. O’Neill.

- Francis Martin, an engineer aboard Train No. 25 who was survived by his wife and children in Spokane.

- Archibald McDonald, a fireman whose body wasn’t discovered until the snow thawed in the springtime.

- Peter Nino, a 37-year-old engine watcher.

- T. L. Osborne, an engineer from Leavenworth, Washington.

- Harry Partridge, a 35-year-old fireman from Biloxi, Mississippi.

- John Parzybok, a 24-year-old rotary conductor from Everett survived by bride of six months.

- Joseph Pettit, the conductor of Train No. 25, who was survived by his wife and children in Everett.

- 35-year-old laborer Antonio Porlowlino.

- William Raycroft, a 31-year-old brakeman survived by his wife in Everett.

- L. Ross, a 25-year-old fireman from Paintsville, Kentucky.

- 50-year-old laborer Carl Smith.

- Andrew Stohmier, a 30-year-old brakeman killed in one of the cabins.

- Vasily Suterin, a Russian laborer of about 35.

- Hiram Towslee, the 36-year-old mail clerk in charge of mail car survived by his wife at Fort Steilacoom, Washington.

- John Tucker, a 37-year-old mail clerk survived by his wife in Spokane.

- Lewis Walker, a 53-year-old steward of Superintendent O’Neill’s private train car who left behind a wife in Everett.

- Julian Wells, a 19-year-old brakeman from Seattle.

- G. R. Yerks, a 24-year-old fireman from Fielding, Michigan.

- Italian laborers Peter Bruno, age 40, Luigi Cimmarusti from Spokane, age 45, Mike Guglielmo from Spokane, age 23, and Giovanni Tosti, age 30.

- And six more unidentified laborers.

The 23 survivors included:

- John Gray and his wife, Anna, from Nooksack, Washington near Bellingham. John suffered a broken leg and minor injuries. Anna’s injuries were fairly severe. Their 18-month-old son, Varden, was also rescued with severe injuries.

- R. M. Laville, an electrician from Missoula, Montana, was rescued with minor injuries.

- Mrs. William May, along with her daughter, Ida Starrett, who was trapped for 11 hours, and Ida’s 7-year-old son, Raymond, suffered severe injuries.

- Henry White, a salesman with the American Paper Company, survived.

- Porter Lucius Anderson was on the sleeping car and survived with minor injuries.

- Samuel A. Bates, a fireman, was rescued after being trapped for six hours beneath an engine.

- Ira Clary, a rotary conductor, was pulled from the snow with minor injuries.

- E. S. Duncan, a brakeman, had to be extricated from the wreckage.

- Ray Forsyth, a section laborer, was sleeping in the passenger car but survived.

- Trainmaster William Harrington and roatary conductor Homer Purcell were actually thrown clear of wreckage but still suffered fairly severe injuries.

- J. L. Kerlee, a brakeman, had to be dug out from beneath a railroad engine.

- And fireman George Nelson, brakeman Ross Phillips, porter Adolph Smith, master mechanic Irving Tegtmeier, and rotary conductor M. O. White, were all rescued with minor to severe injuries.

Alfred Hensel, the only surviving mail clerk from Fast Mail Train No. 27, pulled himself free of the wreckage. In an interview afterward, he said:

“When I came to, I found that I was pinned down with a timber or something over me in such shape that it was impossible for me to move any more than my head. After some difficulty I worked myself out of there, and I did get out on the top of the snow, and at that time all I could see, or the first thing I saw, was the lights up at Wellington, which kind of puzzled me, as before they were on practically a level with us, where the trains were, and at this time they were up the mountain.”

You know, I’ve heard a lot of people talk about haunted places here in Washington State, and the site at Wellington is usually one of the first and foremost mentioned. I’ve been to a lot of spooky, scary places, many of which have been purported to be haunted in Washington State, and I’ve got to say, not once has anything ever happened that’s been cause for alarm. So, I’m not sure if ghosts exist…who am I to make that kind of determination? But it hasn’t happened to me. But maybe something like that has happened to you. Send me an e-mail at erich@washingtonourhome.com and let me know if you’ve experienced anything supernatural here in Washington State. I’d be happy to maybe follow up on that in a future podcast episode.