Earthquakes in the Pacific Northwest

Podcast: Play in new window | Download | Embed

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | RSS | More

Two weeks after Valentine’s Day, 2001, a magnitude 6.8 earthquake struck the south sound region of Washington state near where the Nisqually River empties into Puget Sound. It was nearly 11 a.m. on a Wednesday, and the state legislature was in full swing. The violent tremors lasted nearly a minute, rocking the state capital of Olympia and the nearby cities of Lacey, Tumwater, Nisqually, DuPont, and Shelton. The shocks registered as far away as Oregon, Idaho, and Canada.

Legislative staffers either took cover as best they could in a marble and sandstone building, or ran screaming into the streets as the iconic dome of the century-old capitol building cracked, splintering a support buttress. If it weren’t for previous earthquake-resistance work, the dome might have collapsed, pulled down from within by the weight of the Volkswagen-sized chandelier in the capitol rotunda, which ominously swayed back and forth for hours after the tremor.

Property damage estimates up and down western Washington totaled in the billions. One person died of a heart attack and nearly four hundred were injured. This was a large earthquake that hit in the Puget Sound region…but it wasn’t the first. Not by a long shot.

My father, the senior fearless field guide, told me about a new show on NatGeo, available through Disney Plus, called X-Ray Earth. It offers an unprecedented look inside our planet using underground monitoring sensors scattered across the world. Many of those sensors – some 1,100 in fact – are located here in the Pacific Northwest and just off our coastline. The data provided by these sensors confirms what scientists have been warning us about for years. The entire western edge of North America sits atop a geologic hotspot known as a subduction zone, which ultimately is what puts us most at risk for earthquakes.

But let’s back up just a bit…say you don’t know anything about geology. Or geography. Or even earth’s northwestern hemisphere, for that matter. Here’s a quick and dirty summary of how plate tectonics work to help prime our discussion on earthquakes today.

Geology 101

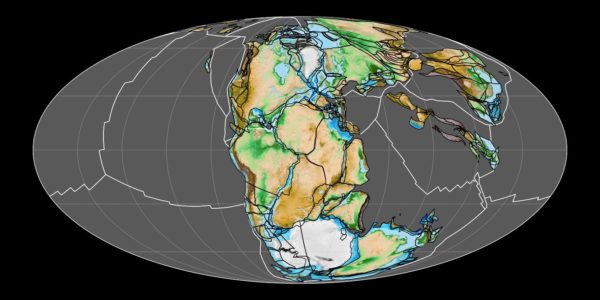

Millions of years ago, the surface of the earth consisted of one enormous land mass called Pangea, and an even more enormous body of water called Panthalassa. All of this land and water floated atop a planetary lake of magma (which is basically superheated, molten rock and metal – we call it lava once it reaches the surface). The land and water made up the earth’s crust, and the magma just beneath it made up what’s called the earth’s mantle.

Boiling hot rock and metal tends to be very active, generating gasses and building pressure in various places, and swirling around the planet as it spins on its axis in space. Because of these forces, weak spots along the earths crust, both underwater and on land would crack open to allow a release of this pressure, and hot magma would come to the surface, sometimes building mountains over eons and sometimes just pushing open the crack wider and wider as the lava cooled and became new land.

After millions of years of this geologic activity, those cracks eventually reached the ocean and water rushed in, separating the land mass into two pieces slowly drifting apart. This was happening in countless places all over Pangea and under the ocean, and over time those land masses that drifted apart became the continents that we recognize on earth today. It all happens so slowly that it can barely be registered as movement…but rest assured, it is happening. And under the surface, the boiling ocean of magma is just as active as ever.

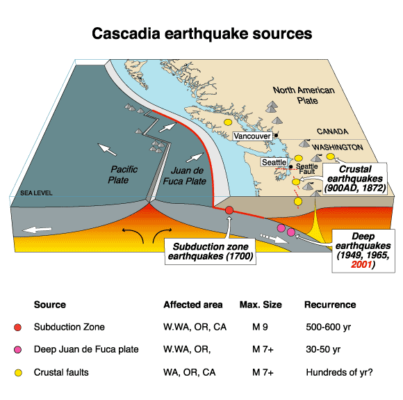

Eventually, the chunks of land floating around on the magma were called tectonic plates and given names. The mammoth plate resting under the Pacific Ocean is called the Pacific Plate, and the one supporting North America is called the North American Plate. Here in Washington, we live atop a tiny shard of one of those two plates called the Juan de Fuca plate, a microplate named for the Greek explorer who sailed the area between Vancouver Island and the Olympic Peninsula on behalf of Spain’s King Philip the Second in 1592.

So we’ve built cities, highways and civilization atop this intersection of unfathomably large tectonic plates that just happen to be crashing into each other, with North America traveling about 2.3 centimeters per year and the Pacific Plate sideswiping it at about 7 to 11 centimeters per year. As the two plates collide, one of them is buckling under the other. Imagine taking two sheets of paper on a smooth table and pushing them together. One of them will start to bulge and deform until the pressure becomes too great, then it will suddenly snap free and slip beneath the overtaking sheet. That’s exactly what’s happening on a planetary scale to these two plates. The Pacific Plate traveling northwest is being pushed under the North American plate as it travels in a southwest direction.

This process is called subduction, and we live atop the Cascadia subduction zone. Like the paper example, when the pressure between the two plates reaches a breaking point, the rift snaps as one plate is folded under the other. That is what causes an Earthquake.

How’s that for a crash course in geology?

A peek inside

Now that we know how earthquakes happen in the Pacific Northwest, lets get back to the NatGeo show, X-Ray earth. The very first episode of the pilot season is all about looking inside the earth beneath Washington state to get a closer look at these geologic forces at work. It is a fascinating documentary series complete with computer generated animation showing what will happen to Seattle when the big one hits. I highly recommend giving it a view.

One of the things we learned from the program was that a major fault lies just 80 miles off the Pacific Northwest coast, and the pressure has been silently building for over 300 years. When it slips (not if), it will generate a megaquake and a tsunami that will devastate the region, threatening the lives of 15 million residents living above the Cascadia subduction zone.

What’s worse, the entire area underneath Seattle and Elliott Bay specifically is essentially a gigantic basin of bedrock filled with soft soil rising up beneath our feet. In one dramatic experiment, you can plainly see how the ridges of this underground basin would reverberate and magnify shock waves, turning the softer soil to a kind of soup. The effect is known as liquefaction, and it presents one of the largest dangers the Pacific Northwest would have to grapple with in the event of a megaquake.

After seeing what happened to double-decker freeways in California after a major earthquake, it’s a very good thing that Washington decided to dismantle our Alaskan Way Viaduct, lest thousands of commuters be trapped or killed when the two layers pancake together during a major seismic event.

After seeing what happened to double-decker freeways in California after a major earthquake, it’s a very good thing that Washington decided to dismantle our Alaskan Way Viaduct, lest thousands of commuters be trapped or killed when the two layers pancake together during a major seismic event.

It’s happened before

As it happens, Washington state is no stranger to earthquakes. According to Wikipedia, there have been 10 earthquakes larger than a magnitude 5.0 in the past 300 years.

The first occurred on January 26, in the year 1700. Scientists have figured out that it hit around 9 p.m. Pacific Time and registered a magnitude between 8.7 and 9.2. The 1700 quake was so powerful, it triggered a tsunami which reached the shores of Japan approximately 10 hours later. Although there are no written records in our region from that time, the timing of the earthquake has been inferred from Japanese records of a tsunami that does not correlate with any other Pacific Rim quake.

The most important clue linking the tsunami in Japan and the earthquake in the Pacific Northwest comes from studies of tree rings taken from cedar trees along the Washington and Oregon coastlines. These particular trees scattered across beaches in Oregon and on the Copalis River in Washington, are known as “ghost forests” since they were all killed by a sudden lowering of coastal land into the tidal zone by the earthquake. You can get a lot of great information about these places in the NatGeo program.

There are also Indian legends that correspond to roughly the same time period. Virtually all of the tribes in the region have at least one traditional story of an event much stronger and more destructive than any other that their community had ever experienced. Stories from the north end of Vancouver Island report a nighttime earthquake that caused nearly all the houses in their community to collapse. Cowichan stories from Vancouver Island’s inner coast speak of a nighttime earthquake, causing a landslide that buried an entire village. Makah stories from Washington speak of a great nighttime earthquake, of which the only survivors were those who fled inland before the tsunami hit. The Quileute people in Washington have a story about a flood so powerful that villagers in their canoes were swept inland all the way to Hood Canal.

A little more than a century and a half later, Washington was struck by another series of earthquakes in the North Cascades region. The 1872 quake and subsequent aftershocks began around 9:40 p.m. Because the earthquake occurred before seismometers were a thing, the magnitude of the shock and its location were never precisely determined, but scientists studied the intensity reports for the event and proposed various epicenters based on this limited data.

One study estimated a magnitude of 6.5 to 7.0, with a proposed epicenter on the east side of the Cascade Range near Lake Chelan. The results of a separate study indicated that it may have been a larger event, placing the shock directly under Ross Lake in the North Cascades. During the initial 24 hours, the aftershocks were strong enough to be felt in Idaho and into southern British Columbia. The intensity of the shocks waned as time passed, but a year after the main quake they were still occurring. The area around Entiat remained seismically active well into the 20th century, leading to speculation that earthquakes were long-lived aftershocks from the 1872 event.

A lost treasure

One fascinating legend from that time period involves a certain US Army Cavalry Captain named Benjamin Ingalls. In 1855, Ingalls was surveying in the North Cascades when he reached a canyon that contained three alpine lakes connected by a mountain stream. He described the two outer lakes as dark and bottomless, but the middle lake he observed was a sparkling emerald color. On closer inspection, Ingalls found that the shore of the middle lake was littered with gold ore embedded in quartz.

Ingalls was, of course, overjoyed, and hastily finished his surveying mission. He made a map to the lakes and buried it near what is now Mount Stuart, with the intention of returning later without his men. In the spring of 1861, Ingalls took his son, Benjamin Jr., and a few trusted friends and joined a prospecting group headed from Portland, Oregon, to British Columbia, along the eastern side of the Cascade range. Secretly, they detached from the group at Peshastin, and headed east into the mountains in search of the lake of gold.

As the group proceeded on foot, they passed a thicket of trees. Some low-hanging branches caught the trigger of a rifle carried by the man following Ingalls. The rifle discharged and Ingalls was shot in the back. He lingered for two days, as his companions reversed course and carried him back toward Peshastin, allowing him to relate details of the map and the lake’s location to one of his friends before he succumbed to his injury. He was buried across from the mouth of the Wenatchee River on the Columbia River’s eastern bank.

When the North Cascades quake hit, it is speculated that the force was so powerful that it crumbled the mountaintops surrounding the valley, burying the lakes in earthquake debris. Ingalls’ companions mounted several successive attempts to locate the gold based on his dying description of the location, but were never successful.

20th century quakes

On April 29, 1945, there was a magnitude 5.5 quake centered near North Bend that did some minor damage here in Washington. Chances are it was overshadowed by the ongoing WWII Battle of Okinawa, the sudden death of President Franklin D. Roosevelt a few weeks earlier, and the confirmed suicide of Adolf Hitler – which happened the very next day.

A 7.3 earthquake struck Vancouver Island in 1946, one of the most damaging earthquakes in the history of British Columbia. This is Canada’s largest onshore earthquake. In Washington State, some chimneys fell at Eastsound on Orcas Island and a concrete mill was damaged at Port Angeles. In Seattle, some damage occurred on upper floors of tall buildings, and one bridge was damaged. The shock was strongly felt at Bellingham, Olympia, Raymond, and Tacoma. And the earthquake was powerful enough to knock the needle off a seismograph at the University of Washington.

Three years later, a 7.1 magnitude quake struck between Olympia and Tacoma, killing 8 people and injuring 64. Damage in Olympia from the earthquake was estimated between $500,000 and $1 million by Governor Art Langlie. Eight buildings on the state capitol campus were damaged by the earthquake, as well as the Old Capitol Building in downtown Olympia, and a 23-ton cradle on the east tower of the Tacoma Narrows Bridge fell 500 feet, injuring two men.

The earthquake caused geysers to explode along the railroad track in the Tacoma tidal flats and in Puyallup. Chimneys throughout western Washington collapsed. In Seattle, nearly every building in the Pioneer Square neighborhood was affected in some way, with damage ranging from lost parapets to entire floors and in some cases entire buildings needing to be demolished over the following years.

A couple of quakes in more recent memory happened in the 1960s. One struck Clark County in 1962, and another just south of Seattle in 1965. The ’65 quake registered a 6.7, causing about $20 million in damages and killing seven people, three by falling debris and four others from heart attacks. Single-story unreinforced brick buildings took the brunt of the damage, and minor damage like fallen chimneys and cracked mortar was reported everywhere.

The two Boeing plants at Renton and Seattle, both built on artificial fill and mudflats, suffered major damage. Nearly a quarter mile of Union Pacific railroad tracks hung suspended in the air after fill dirt slid away from beneath part of the line just outside Olympia. The capitol building suffered cracking to the dome and supporting buttresses, leaving it in a condition where a major aftershock could have caused complete collapse.

Tragedy leads to innovation

The damage and deaths in the 1965 earthquake were tragic, but they helped bring about the installation of the Pacific Northwest Seismic Network in 1969. The PNSN collects and studies ground motions from about 400 seismometers in the states of Oregon and Washington. PNSN monitors volcanic and tectonic activity, gives advice and information to the public and policy makers, and works to mitigate earthquake hazard.

It was the PNSN that successfully used seismic activity data to predict the 1980 Mount St. Helens eruption, after which monitoring was expanded to other Cascade Mountains volcanoes. The Pacific Northwest Seismic Network, in conjunction with the Cascades Volcano Observatory of the US Geological Survey, now monitors seismic activity at all the Cascade volcanoes in Washington and Oregon.

Thirty six years after the 1965 quake that created the PNSN, the Nisqually earthquake of 2001 prompted a significant expansion of the network as well as the demolition of Seattle’s structurally unsound Alaskan Way Viaduct.

Following the quake, authorities temporarily closed many buildings and structures in the area for inspection, including several critical bridges, all state offices in Olympia, and Boeing’s factories in the Seattle area. Various schools across the state also closed for the day. The Fourth Avenue Bridge in downtown Olympia was so heavily damaged that it had to be torn down and re-built. In Seattle, the Alaskan Way Viaduct was replaced with the State Route 99 Tunnel and an expanded Alaskan Way on the footprint of the old viaduct. The new tunnel is designed to withstand a magnitude 9.0 earthquake.

What have we learned?

Do you remember where you were when the 2001 Nisqually Quake hit? Many of my former colleagues in the Washington State Legislature lived through that nightmare and have shared their memories with me.

At the time, I was in my Spokane apartment building when I heard what I thought was the sound of a garbage truck that had backed into a dumpster. It sounded like it came from very nearby, like the complex parking lot. As I later learned, it was the Nisqually quake that I had felt…some 320 miles away.

A 2014 book written by Seattle Times science reporter Sandi Doughton is called Full-Rip 9.0, The Next Big Earthquake in the Pacific Northwest (published by Sasquatch Books). It introduces readers to the scientists dedicated to understanding the way the earth moves and describes what patterns can be identified and how prepared (or not) we are here in the Greatest State in the Lower 48™. With a 100% chance of a mega-quake hitting the Pacific Northwest, this fascinating book reports on the scientists who are trying to understand when, where, and just how big the big one will be.

For more information on how to prepare in the event of an inevitable earthquake, please visit www.ready.gov to learn how to drop, cover and hold, make an emergency plan, and protect yourself and your loved ones when the big one hits.