Virginia V and the Mosquito Fleet

Podcast: Play in new window | Download | Embed

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | RSS | More

Before there were roads around the Puget Sound region, there were rivers. Before the stagecoaches, there were Salish canoes. And before the planes, the trains, and the automobiles…there was the water, and the ships that traveled upon it. In the earliest days of human habitation in what is now Washington State, the fastest way to get from place to place around the Salish Sea was by paddling a canoe, whether to find a quiet spot to fish, hunt down a whale, race for bragging rights, visit and trade with neighboring tribes, or mount a seaborne offense to help secure your way of life.

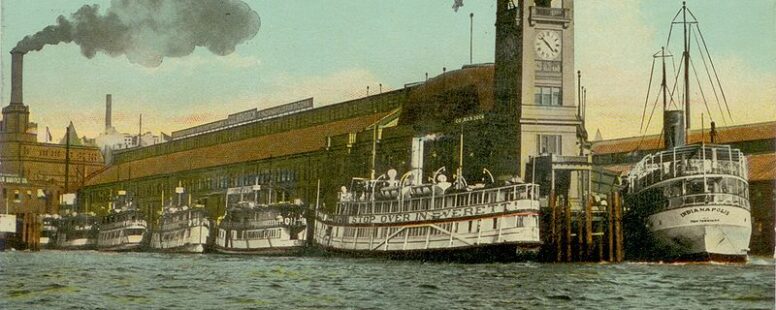

When Spanish, British and later American explorers first entered what is now known as Puget Sound, they brought with them massive, tall ships capable of carrying armies across oceans. Aboard these tall ships were small ships, like gigs and other types of rowboats, which soon became more prevalent upon the water after settlement by the first non-natives in the region. As more and more settlers took root in the area, the need for better boats led to the development of steam vessels – some with propellers, some with paddlewheels, and all designed primarily to move people and goods back and forth across the inland sea. At first, enterprising entrepreneurs obtained a boat and began ferrying folks for a small fee. As their profits grew, they built bigger and faster steamships to carry more people, food and supplies, cattle and machinery. By the 1860s, there were hundreds of steamers crisscrossing the Puget Sound, every day, all day. There were, in fact, so many ships upon the water at any given time, that an article in the Tacoma Daily Ledger on February 21, 1889, implied that when viewed from a lofty point, the fleet looked like a swarm of mosquitos skimming over the green waters of the Sound.

And the nickname stuck. No one knows for certain how many ships were considered part of the Mosquito Fleet during its boom period between the 1880s and the 1920s, but estimates range from around 700 to as high as 2,500. In the time before roads and extensive rail lines, these vessels were the threads that helped knit together our communities. Each one of those ships has a unique and fascinating story to tell, but most are lost to history. In fact, there are only two that still remain in existence today.

Numbering in the hundreds (to possibly thousands), an A-to-Z list of just some of the Mosquito Fleet ships from the HistoryLink website includes names like the Alida, Black Prince, C.C. Calkins, Dix, Elwood, Flyer, George E. Starr, Hyak, Inland Flyer, Josephine, Katahdin, L.T. Haas, Maude, Nisqually, Otter, Potlatch, Quick Step, Rosalie, State of Washington, Telegraph, Urania, Verona, West Seattle, Xanthus, Yellow Jacket, and Zephyr.

But let’s begin at the beginning.

In 1836, the reliance on wind and human energy to power boats lessened when steam-powered transportation reached Puget Sound in the form of a legendary 101-foot-long vessel, the Beaver.

It was built in London for the Hudson’s Bay Company as a paddle wheeler, then converted to a sailing ship to travel to the United States, then converted back to a paddle wheeler once it reached the North American west coast. Over the next several decades, the Beaver plied the Sound, carrying goods, people, and machinery. The Beaver served trading posts maintained by the Hudson’s Bay Company between the Columbia River and Alaska, then belonging to Russia, and played an important role in helping maintain British control over the region.

In 1874, the HBC sold the Beaver to the British Columbia Towing and Transportation Company which used it as a towboat until 1888 – when an inebriated crew ran her aground on rocks near Vancouver, Canada. The wreck remained on the rocks until 1892 when the wake of a passing steamer finally knocked it into the water where it sank…but not before enterprising locals had stripped much of the wreck for souvenirs. If you want to see some of them, the Vancouver Maritime Museum houses a collection of Beaver remnants including the boiler and two drive shafts for the paddle wheels.

When the Beaver first hit the waters of Puget Sound, it proved that steam-powered vessels were the way to go for the area’s new settlers. The only problem was that the British owned the Beaver, and Americans wanted steamships of their own. In 1853, Puget Sound’s residents got their wish with the arrival of the sidewheeler, Fairy. Traveling from San Francisco on the deck of the bark Sarah Warren, the little boat reached Olympia on October 31st and became the first American-owned steamer on Puget Sound. It was also the first to have a formal sailing schedule, published for the first time in the Columbian newspaper of Olympia. The “splendid steamer,” as she was advertised, was supposed to make two trips a week between Olympia and Steilacoom on Mondays and Wednesdays, and one trip a week from Olympia to Seattle on Fridays. Fares were high: $5 for Olympia-Steilacoom, and $10 for Olympia-Seattle (in today’s dollars, that would be about $200 bucks from Olympia to Steilacoom and almost $400 to get to Seattle). Fairy, however, proved unseaworthy in rough winter weather and was eventually replaced by a sailing schooner. Following her failure on the sound, Fairy ran the much shorter Olympia-Fort Steilacoom route until 1857, when her boiler exploded. No one was killed, but that was the end of the Fairy.

The year after the Fairy was launched, the British Hudson’s Bay Company brought a second steamer to the region and named it the Otter. A sidewheeler, the Otter serviced HBC trading posts between Puget Sound and Alaska until she sank for unknown reasons in 1880.

Salvaged and put back into operation as a coal barge by the Canadian Pacific Navigation Company, the Otter finally met its demise in 1895 when the company beached the ship and burned the hull to recover the scrap metal within.

The age of steam had arrived in the Pacific Northwest, and the next major Mosquito Fleet vessel to arrive on Puget Sound was the Major Tompkins, a 97-foot iron-hulled propeller-driven steamship. When it first docked in Port Townsend, residents there saluted the steamer by firing their pistols into the air. It then chugged slowly south to Steilacoom (its top speed was only about 5 miles per hour), where residents blew up stumps in celebration, before it finally landed in Olympia on September 20, 1854. Not ones to waste time with multiple words, residents there soon nicknamed the ship Pumpkins and used it to carry freight, passengers, and best of all, mail, which at that time did not have the most reliable service. But early the following year, a winter squall caused a navigation error that drove the squat steamship into rocks near Esquimalt, on the south end of Vancouver Island. No one died, but the Major Tompkins was a total loss.

Around the same time, another steamship was being taken apart in Philadelphia to be transported in pieces to the Puget Sound and reassembled as the Traveler. It had an iron hull but was sheathed in wood to ostensibly prevent leaking and was the first boat to steam up the Duwamish, Nooksack, Snohomish, and White rivers. But on March 2nd, 1858, at 11 p.m. off Foulweather Bluff at the entrance to Hood Canal, heavy weather forced the captain to steer toward shore to wait out the storm. Unfortunately, the Traveler steamed a bit too close to shore, ran aground and began to break up. Of the crew of eight, only engineer Thomas Warren and two Native American crewmen were able to swim to shore. The other five people aboard died in the accident and the Traveler sank in about 30 feet of water and at low tide you could still see her smokestack poking out above the waves. Would-be salvagers tried to pull off the smokestack from shore using teams of horses, but only succeeded in pulling the hulk into deeper water – where it sat undisturbed until 1990, when the wreck was located by divers.

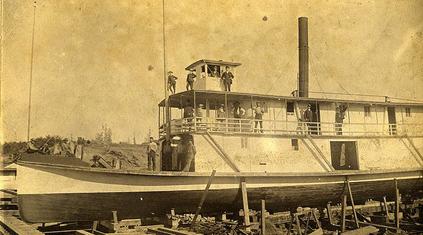

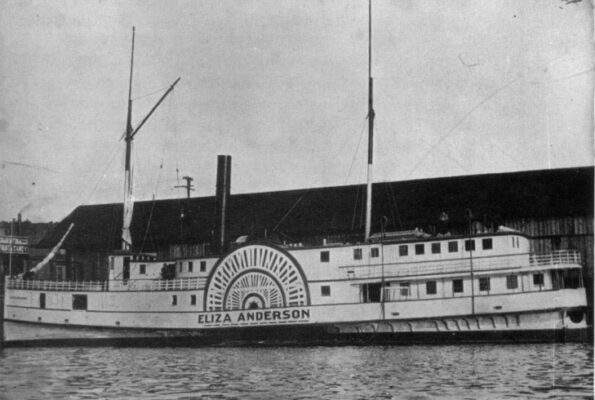

The same year the Traveler sank, work began on a steamship called the Eliza Anderson, which started running passengers, materials and mail from Olympia to Victoria, British Columbia, in January 1859. Curiously, the ship also included a steam calliope which played a variety of tunes including Yankee Doodle and The Star-Spangled Banner, which must have annoyed Canadian travelers coming south from Victoria.

The 140-foot side-wheeler built from Douglas fir in Portland, Oregon, was by no means a fast ship – but it is considered to be the first to make a profit in the Mosquito Fleet era. Traveling from Olympia to Seattle cost $12, and to go all the way to Canada cost $20 per person. Again, in today’s dollars that would be $450 and $750 respectively! In contrast, a ticket from San Francisco, California, to Portland, Oregon, aboard the steamer Brother Jonathan ran $5 for a cabin and just $2.50 in steerage.

Aside from the ongoing fare wars between the Eliza Anderson and her competitors, the storied steamer is famous for another reason. On September 24, 1860, a 14-year-old black youth named Charles Mitchell hid on board the ship seeking passage to Canada to escape slavery. He and another, older black man had been working on the vessel as “temporary stewards,” and the man helped Mitchell find a hiding place on board. He was discovered either at Steilacoom or Seattle and was not taken into custody right away because he promised to work off his passage. Coincidentally, Washington’s acting territorial governor Henry M. McGill and his family were also on the Eliza Anderson. Mitchell confided to McGill’s son that he intended to desert the ship in Victoria. The son told his father, who then told the ship’s officers, and when they were just four miles out of Victoria, they seized Mitchell and held him in “close confinement.”

Once in Victoria, word got out that Mitchell was being held against his will aboard the Eliza Anderson and a group of protesters composed of both white and black citizens of Victoria marched down to the dock. A lawyer presented a petition for a writ of habeas corpus to the local chief justice, who granted the writ. Armed with the writ, the local sheriff and a police constable boarded the Eliza Anderson, presented the writ to the officer in charge, and demanded that Mitchell be released to them. The officer in charge told them to talk to the captain, who told them to talk to Governor McGill. McGill went ashore and – depending on the source – either gave in to the Canadian court’s demand or protested vociferously against it. Either way, Mitchell was removed from the vessel by the Canadian authorities and became a free man.

By the 1870s, faster ships like the J.B. Libby, Mary Woodruff, Pioneer, Alexandra, and Jenny Jones overtook both the Eliza Anderson‘s pace and profit, and it was eventually relocated to Alaska’s Dutch Harbor in the Aleutian Islands, where it was later beached and abandoned in 1898.

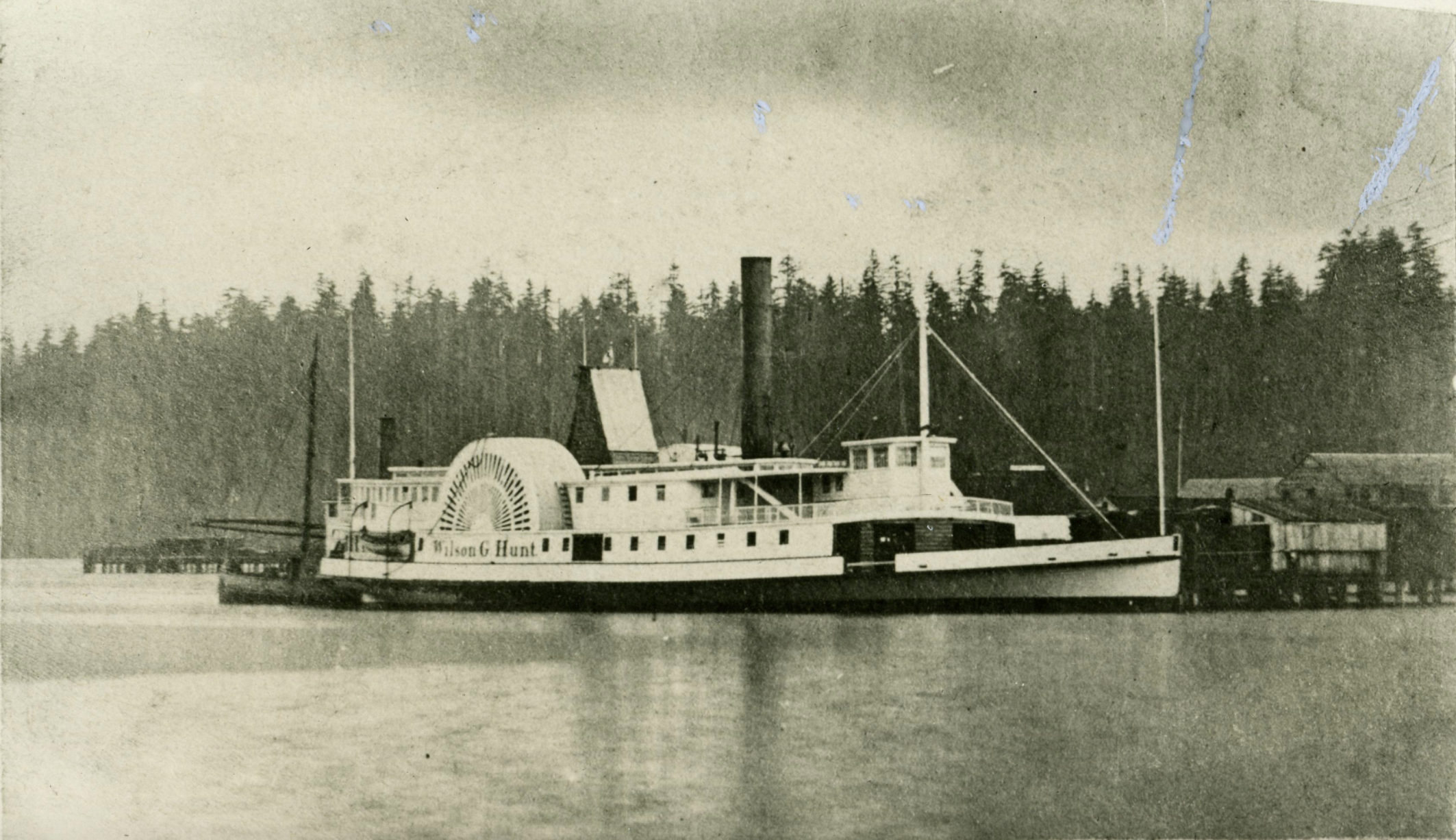

Like the Eliza Anderson, the sidewheel steamer Wilson G. Hunt began its Puget Sound service in 1858 as well. Built in New York in 1849, the vessel was 185 feet long, 25 feet wide and had a 6.75-foot depth of hold. The Hunt had an old “steeple” style steam engine, and its low-pressure boiler could drive the vessel at 15 knots. The most unusual feature of the Wilson G. Hunt was the unusual housing for her steeple engine that resembled an enormous wedge of cheese.

The Hunt was a mail runner for a while before mechanical problems forced it into early retirement. It was used on the Columbia River and the Fraser River for a time, but in 1884, the Wilson G. Hunt was laid up in Victoria’s inner harbor where it stayed until 1890. The decision was made to junk the ship, and she was ultimately burned to recover her scrap metal.

Domingo Marcucci built the sidewheel steam tug Cyrus Walker at his California shipyard in 1864. She was 120 feet long with a 28-foot beam and an 8-foot hold and equipped with two high-pressure steam engines. Marcucci sent the Cyrus Walker to Puget Sound to tow logs for the Pope & Talbot lumber mill, but it found service in the burgeoning Mosquito Fleet as soon as 1866 and was active at least through 1883.

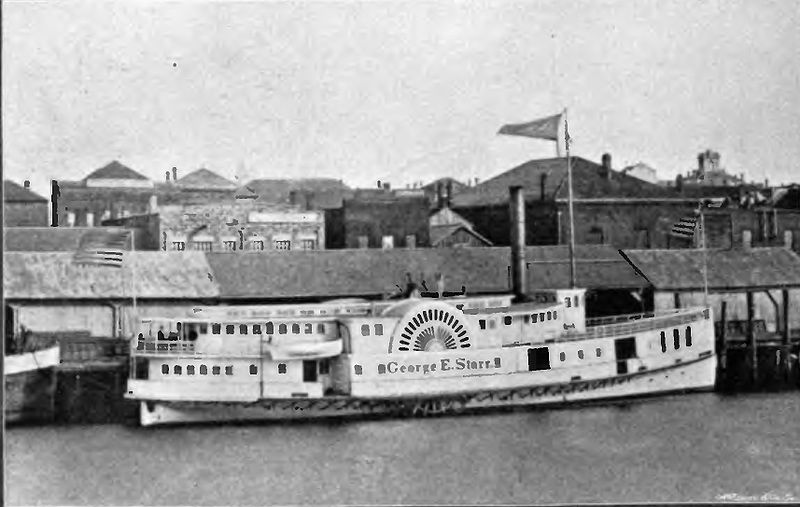

The sidewheel steamer George E. Starr was built at Seattle in 1878 for the Puget Sound Steam Navigation Company’s international route to Victoria. It was 148 feet long with a 28-foot beam and 9-foot depth of hold. The George E. Starr was considered sufficiently elegant at that time to allow President Rutherford B. Hayes to spend a night in one of her cabins while visiting Seattle.

By 1904, the ship was making trips from Seattle bound for Whatcom, Fairhaven, Anacortes, and Blaine where travelers could make connection with a steamer bound for Point Roberts. The George E. Starr served a long time, and toward the end of its career had acquired the reputation as a very slow boat – so much so that locals made up a song about her, set to the tune of Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star.

Paddle, paddle, George E. Starr, How we wonder where you are.

Leaves Seattle at half past ten. Gets to Bellingham, God knows when!

As you creep across the bight, We can see your masthead light,

Out upon the bay so far, Paddle, paddle George E. Starr.

Maneuvering the old boat was apparently difficult, and when making turns, she would list over to one side and not right herself. As a sidewheeler, this caused the ship to spin around in circles, so to prevent this from happening, her skipper set up a counterbalance on the deck consisting of an old cart loaded with two or three tons of old anchor chain. When she was finally past her prime, the George E. Starr was finally abandoned on the shore of Lake Union, where she rotted and slowly sank from existence.

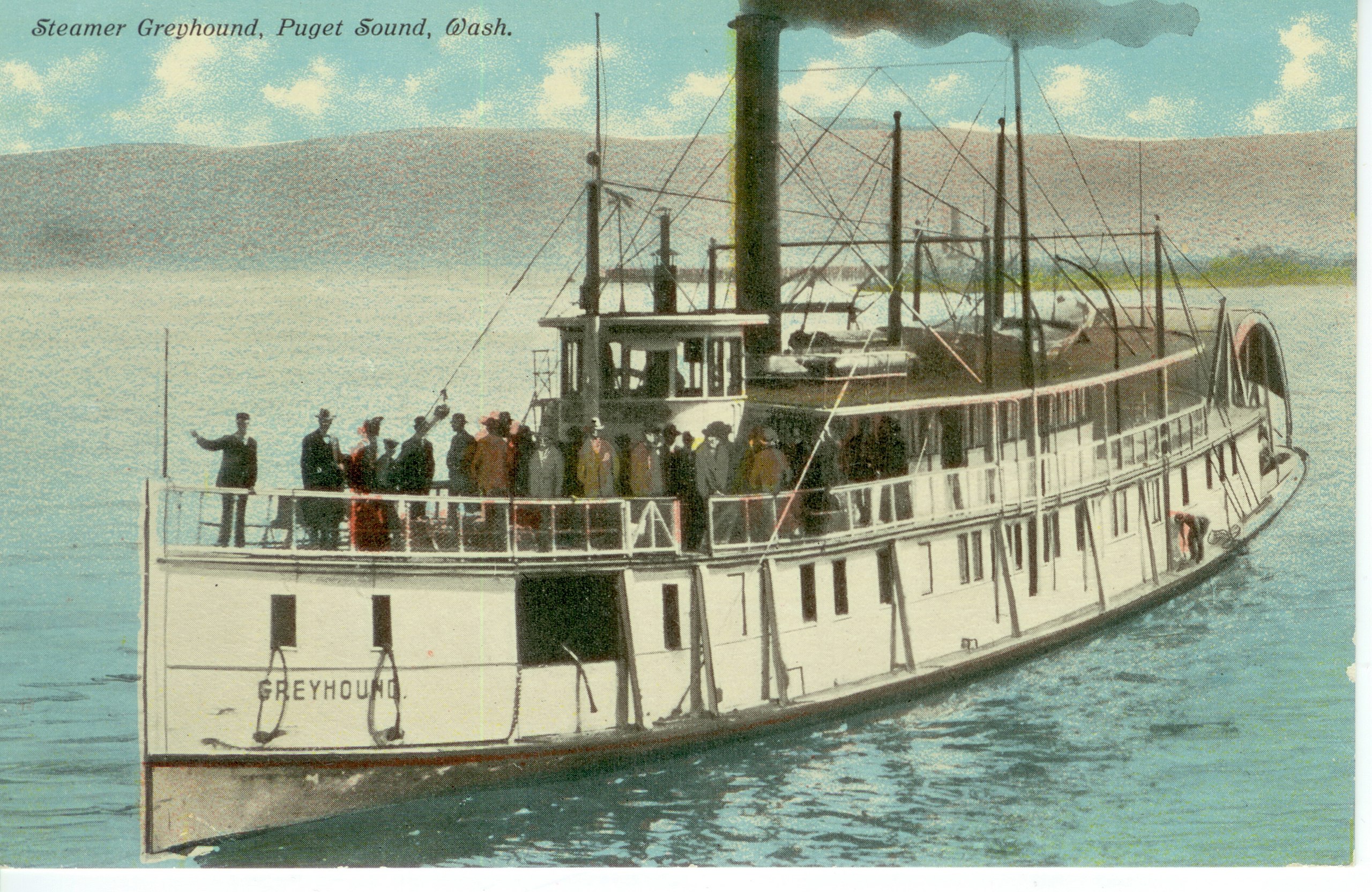

Around 1890, a new boat launched that soon put all others to shame. The Greyhound was an express passenger steamer that was never intended for a dual role hauling both freight and people. She was purpose-built to carry passengers and do it fast. This vessel, commonly known as the Hound, the Pup, or the Dog, was 139.3 feet long, only 18.5 feet on the beam, and with a 6.3-foot depth. Twin steam engines drove the enormous sternwheel, which made her one of the fastest ships on the Sound at the time.

She raced (and beat) all the fastest boats on the Tacoma and Seattle route, including the Fleetwood – a 111-foot long, propeller-driven, steamer built in 1880. In 1889, Fleetwood made record time on a trip from Olympia to Seattle to carry a steam fire engine to the aid of that city during its great fire. But despite many years of speedy service in the Mosquito Fleet, the Fleetwood was ultimately abandoned in 1898 on the beach in Quartermaster Harbor where she slowly rotted away over time.

The Greyhound was said to be “all wheel and whistle,” and had both a silver greyhound statue on the roof of her pilot house, very much like a hood ornament on a fancy car, as well as a broom mounted on her masthead, showing that she’d swept the sea of her competition. It was a proud designation she held until April 21, 1891, when the Greyhound raced a relative newcomer – the Bailey Gatzert, built just the year before – 28 miles from Tacoma to Seattle.

That morning, both the Gatzert and the Hound were at the dock in Tacoma when rumors began to spread that there would be a race between the two vessels on the route back to Seattle. Hundreds of people crowded onto the docks to watch as the confident Greyhound cast off lines and moved out into the water, waiting for the Gatzert. When the captains gave the go ahead to the engine room, both steamers took off from Tacoma at high speed, blowing huge amounts of black smoke from their stacks.

By the time they reached the turning point in the channel at Point Robinson, Bailey Gatzert was well ahead of Greyhound, and the race seemed to be over. They found out later that the Greyhound didn’t have much of a freshwater supply left when they’d started and had to switch to salt water in the boilers, slowing them down. By the time the two ships reached Alki Point, Greyhound started to add more fuel into the firebox, closing the gap to only about 500 yards behind the Gatzert.

At about this time, crowds on the docks in Seattle spotted the two steamers and cheered as the Greyhound continued to gain, but not enough to overtake the Bailey Gatzert, which was first to pull into the dock. The two raced again on the return trip to Tacoma, and this time the Greyhound beat the Gatzert by one and one-half minutes…but that didn’t stop the crew of the Gatzert from mounting both the silver dog statue and the broom on their vessel to brag about the achievement.

In 1911 the new propeller steamer Nisqually replaced the Greyhound, which was then relegated to relief boat service. By 1924, Greyhound had been out of service for so many years that all that remained was her hull. Despite this, she was still in good enough shape to warrant hauling her out in Tacoma in 1924, for repair, caulking and painting. But it wasn’t enough. She very likely met the same fate as so many steamers before her. Abandoned and left on a beach to rot.

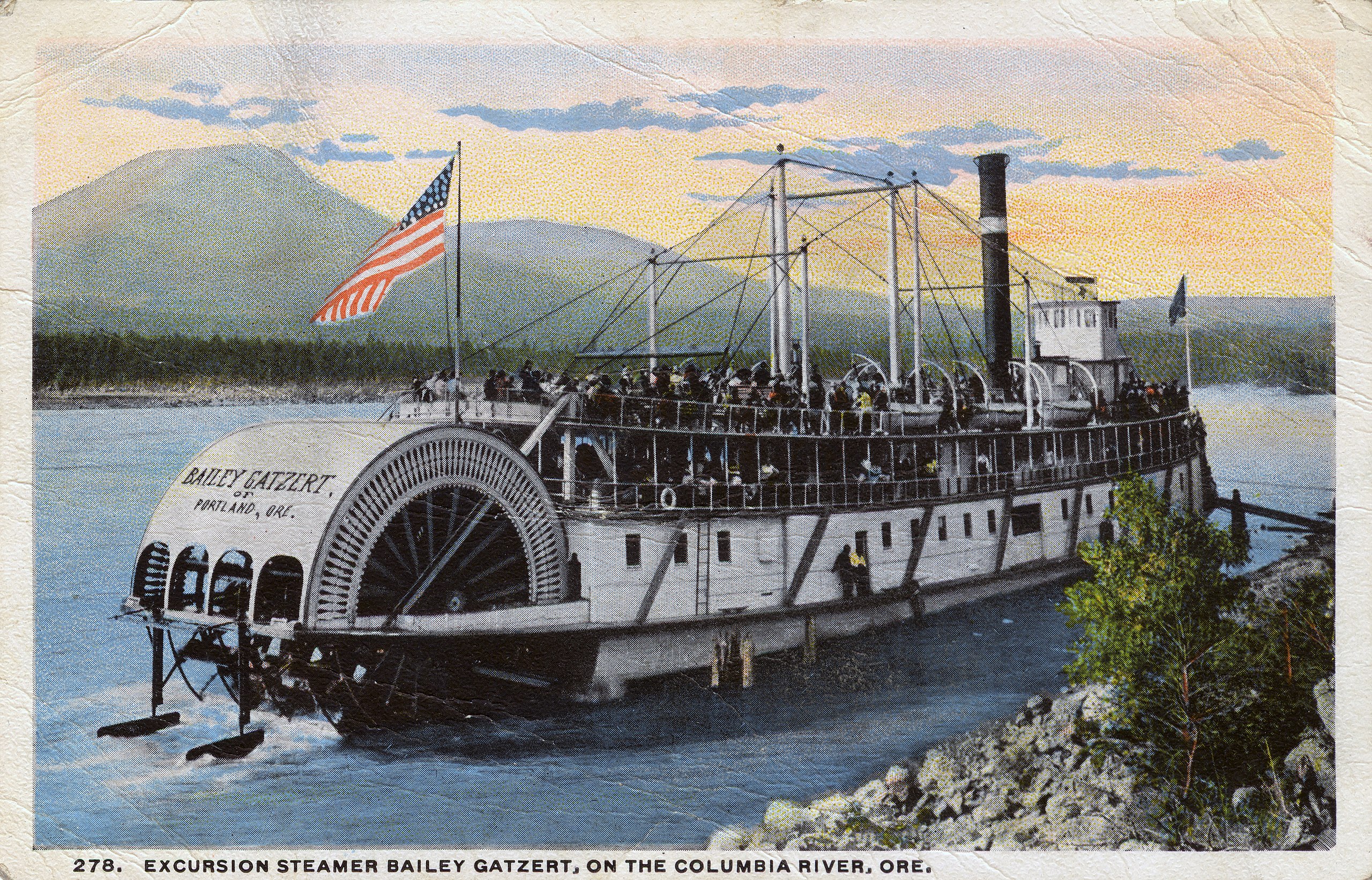

The Bailey Gatzert, considered one of the finest ships of its time. Named after an early businessman and mayor of Seattle, she was built right here in Washington state at a shipyard in Ballard.

- The Bailey Gatzert was driven by two twin horizontally mounted single cylinder poppet valve steam engines, each with a 22-inch interior bore diameter and an 84-inch stroke on the piston rod.

- These engines could drive the steamer at a speed of over 20 miles per hour. According to an official source, the engines generated 1,150 nominal horsepower and 1,300 indicated horsepower.

- The sternwheel had 17 “buckets” (paddles), each of which was 18 feet long.

- The boiler was a steel locomotive type, with a total heating surface of 3800 square feet.

- The firebox had a grate surface of 49 square feet and could consume up to three cords of wood an hour.

- Bailey Gatzert was 177.3 feet in length over the hull with a 32.3 foot beam and 8 foot depth of hold. Her official merchant vessel registry number was 3488.

The Bailey Gatzert spent 2 years ferrying passengers around Puget Sound before she was transferred to the Columbia River. During that time, she raced (and lost to) the steamer T.J. Potter – whose crew then demanded the Gatzert give up the silver dog she’d won in her race with the Greyhound. Gatzert spent another 26 years on the Columbia before reappearing on Puget Sound for the remainder of her extravagant career. After all, she even had a musical arrangement composed for her in 1905, The Bailey Gatzert March (listen to it here!). But time, as with all things, eventually caught up to the old steamer and after changing hands multiple times it finally met its fate in 1929 when it was stripped for parts. In 1930, the hulk of the steamer was sold to the Lake Union Drydock and Machine Works of Seattle, which built a four-story structure on the old hull and used the vessel as a floating shipway and machine shop in Lake Union.

In 1996, the Bailey Gatzert was honored by being depicted on a U.S. postage stamp, and her chime whistle and name plate are preserved in the collections of the Museum of History and Industry in Seattle.

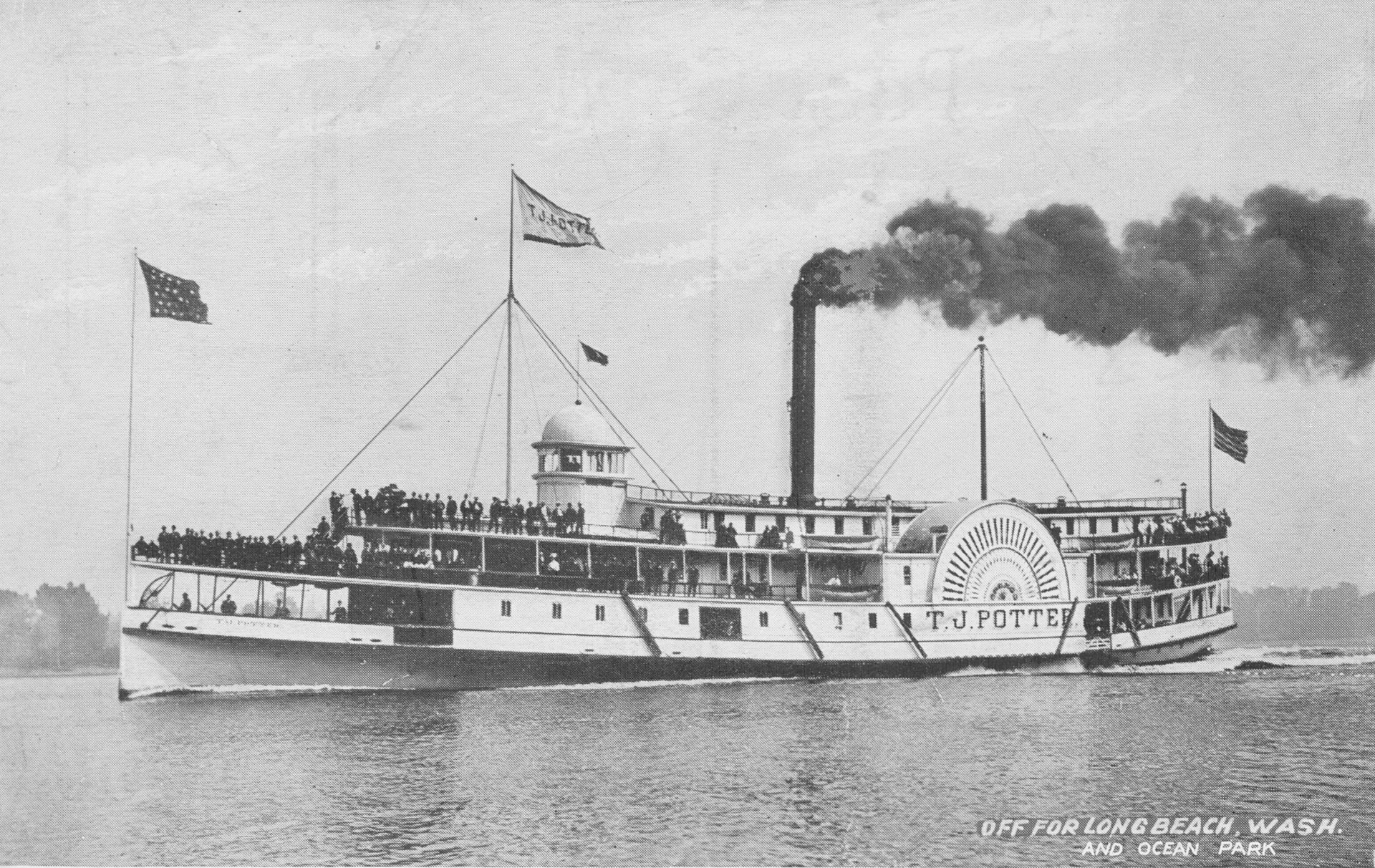

The T.J. Potter, launched in 1888, was one of the fastest and most luxurious steamboats in the Pacific Northwest. According to Gordon R. Newell in his book, Ships of the Inland Sea – The Story of the Puget Sound Steamboats, The T.J. Potter was the final step in the evolution of the side-wheeler—230 feet long, 33 feet beam, with grace and beauty in every inch of her. The T.J. Potter was intended to be the last word in the elegance then incorporated into steamboat design. Even the paddlewheels were decorated with intricate designs. Where those of the lesser side-wheelers were pierced by simple fan designs, hers were jigsawed into an intricate floral pattern that made them works of Victorian art. A divided, curving staircase led up to the grand saloon, and her passengers could observe themselves ascending it in the plate glass mirror, which was the largest in that part of the West. Colored sunlight from the stained-glass windows of the clerestory gleamed on soft carpeting and the mellowed wood and ivory of a grand piano.

As the T.J. Potter aged, she matured into an old but comfortable boat. She had staterooms for the elderly, the rich, or the newly married, and a continuous seat ran all the way around the stern. If the weather was good, the crew would set out deck chairs on the open afterdeck, and the glass-enclosed lounge cabins were said to be comfortable even on cold or rainy days.

Nevertheless, in 1916 the once opulent T.J. Potter was finally condemned for passenger use and ultimately abandoned on the northeast side of Youngs Bay near Astoria, where she was burned and salvaged for her metal shortly afterward.

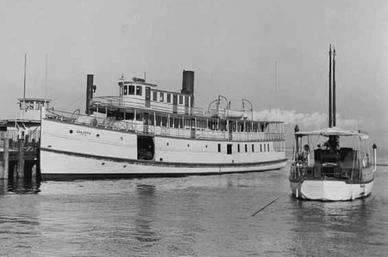

One of the more striking Mosquito Fleet tales is the wreck of the 117-foot propeller-driven steamship Calista on July 28, 1922. Under a thick blanket of fog, Captain Bert Lovejoy disembarked from Langley on Whidbey Island in the late morning, having already made several stops around Puget Sound. Shortly before 11:00 a.m., hearing blasts from ships horns but unable to locate them through the dense atmosphere, Captain Lovejoy stopped the ship off West Point just north of Seattle and tried to get his bearings by listening. Out of the fog, the 9,482-ton Japanese steam freighter Hawaii Maru suddenly appeared off the port bow and rammed the 105-ton Calista at full speed.

Remember the scene in Jurassic Park: The Lost World when the Costa Rican freighter carrying the T-Rex materializes out of nowhere and smashes into the pier at full speed as onlookers flee for their lives? Yeah, I imagine it was probably a lot like that.

The captain of the Hawaii Maru is actually credited with helping prevent the Calista from immediately sinking to the bottom of Elliott Bay by ordering his ship to continue ahead at one-quarter speed, pinning the Calista to its bow. The extra time gave passengers a chance to either board lifeboats or be rescued by the freighter or nearby tugs that came to aid in the recovery effort. By the time the Calista’s forward flagpole finally slipped beneath the surface 28 minutes later, all 70 passengers and crewmembers had been rescued. As reported by the Seattle Post-Intelligencer the following day, other than the mayor of Langley fainting, no passenger suffered so much as wet feet in the marine disaster. The Hawaii Maru later served as a Japanese troop transport during WWII and was torpedoed and sunk by the submarine USS Sea Devil in the East China Sea.

The Calista was wrecked a few years after the accident but is also remembered as being one of two Mosquito Fleet ships that carried Wobblies to what became known as the Everett Massacre in 1916. Wobblies was the nickname for International Workers of the World, a labor movement that came into its own around the First World War.

On November 5, 1916, the steamship Verona followed by the Calista was transporting members of the IWW from Seattle to Everett to support their cause in that city. However, residents opposed to the Wobblies heard about their impending arrival and crowded the dock to await them. On the arrival of Verona in Everett, a shooting broke out and the Verona did not land her IWW passengers. Instead she reversed course, warning the Calista on the return route to turn around. Both ships then headed back to Seattle.

Another dubious distinction is held by the Josephine, a 76-foot sternwheeler launched in 1878 with the boiler and engine salvaged from the 20-year-old steamer Wenat, which had sunk in the Skagit River earlier that year. In January 1883, the Josephine made regular runs between Seattle and the Upper Skagit River on Tuesdays and Fridays. However, on Tuesday, January 16, the vessel left half an hour early, leaving about 10 or 15 people standing at the dock having missed the boat. Little did they know that the maddening inconvenience very likely saved their lives that day.

At about 12:05 that afternoon just off the coast of Mukilteo, the Josephine’s boiler exploded, disintegrating the pilothouse and launching people and debris high into the air. Josephine immediately split in half and the portion containing the remains of the boiler sunk immediately in about 30 feet of water. The remaining piece of the wooden hull stayed afloat, and wounded women and men rushed frantically around in total confusion. One of the lifeboats had stayed intact and carried some of the survivors to safety. Others were rescued by nearby ships that came to assist, and some by Native Americans who saw the explosion from shore and paddled their canoes out to help.

Six crew members and two passengers died as a result of the explosion, and a third passenger later died from injuries suffered in the blast. The cause was later determined to be low water levels in the boiler, resulting in charges of gross and criminal negligence against the ship’s operators. Though nearly destroyed, the floating hull was towed to a nearby shipyard where engineers determined it could be repaired and returned to service. Surprisingly, they kept the same name, Josephine, leaving at least me wondering how confident passengers really were in the years following the explosion.

There are dozens upon dozens more Mosquito Fleet vessels whose histories have been documented either on Wikipedia, at HistoryLink.org, or in a number of books like Mosquito Fleet of South Puget Sound by Jean Cammon Findlay and Robin Paterson, published by Arcadia Publishing – the same company that published my book, Exploring Maritime Washington: A History and Guide (available now!).

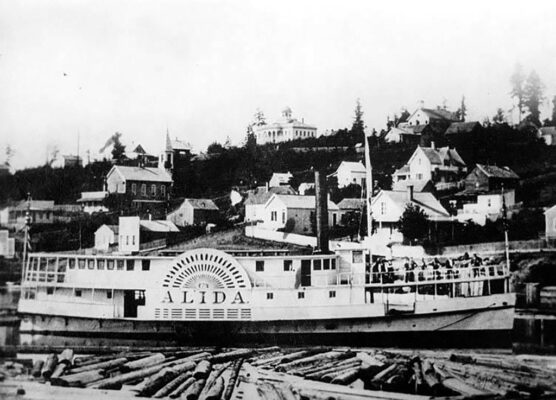

You can learn about the 115-foot, Alida, a beautiful sidewheeler that serviced ports between Olympia and Port Townsend from 1870 to 1890 before meeting a fiery end when a Gig Harbor brush fire swept the shoreline burned her to the waterline.

There’s the 105.5-foot Inland Flyer (later known as the Mohawk) that ran passengers around Puget Sound from 1898 to 1916. It was the first steamship on the Sound to use oil fuel and was later dismantled to donate her useable parts to other ships in the Mosquito Fleet.

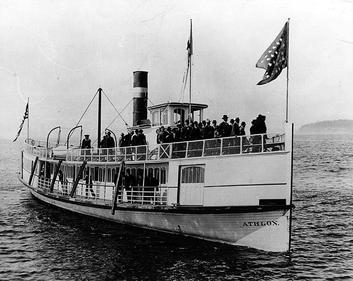

It was crewmen aboard the 112.4-foot steamer, Athlon, moored to the Grand Trunk Pacific dock along Seattle’s waterfront in 1914, that first noticed smoke rising from the warehouse. After calling in the fire department, the Athlon quickly cast off and watched helplessly as the resulting inferno reduced the dock to ashes in just two hours, killing 5 people and injuring 29 more.

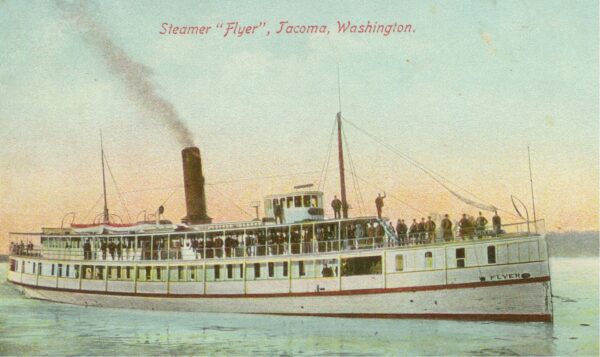

Not to be confused with the Inland Flyer, the exceptionally tall and narrow Flyer was designed to be the fastest propeller-driven vessel in the Pacific Northwest when it was launched in 1891. It promptly flopped over in the water due to a lack of weighted ballast, causing the captain to climb out the nearest window to escape. Later in its career it collided with both the Bellingham and the Dode under tow, causing damage to all three ships.

And there are hundreds of others, with names like Islander, Buckeye, Tolo, and Eagle – which, thanks to the temperance movement was christened with flowers instead of the traditional bottle of champagne, a mistake superstitious mariners pointed to as the reason the ship burned to the waterline only two years after she first launched. Ships like Olympia, later known as the Princess Louise, the Fairhaven, the Clatawa, the Camano, and the North Pacific, which smashed into a rock and sank off Marrowstone Point, nearly the same fate suffered by her running mate, the Mainlander just an hour later in the same spot.

The Isabelle, the Hyak, the Kitsap, the Reliance, the Utopia, and the Atlanta. The Hassalo, the Henry Bailey, and the Suquamish – the first diesel-powered passenger ship built in the United States. The Annie M. Pence, which burned to the waterline in 1895 and was later rebuilt as the T.W. Lake, which took 700 barrels of lime to the bottom of Rosario Strait and 14 men to their death when it foundered off Lopez Island in December of 1923. There are as many stories as there are ships in the fleet, and as many ships as mosquitos in a swarm. I wish I could tell all of them here, but some discoveries have to be made on their own.

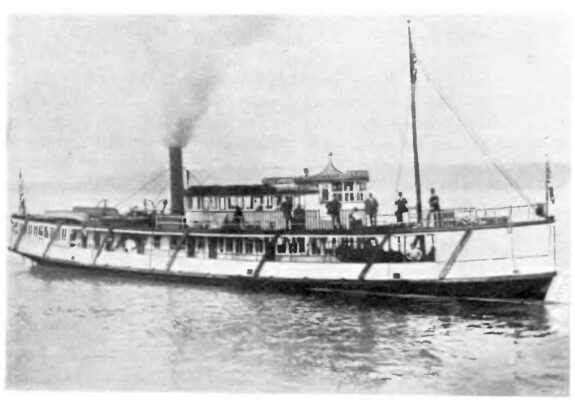

I recently had the opportunity to tick off one of my bucket list items when the good folks at Olympia Harbor Days and Exploration Tours, I was invited to be the historical tour guide during a three-hour cruise from Percival Landing on Budd Inlet all the way to Foss Waterway on Commencement Bay in Tacoma aboard the Virginia V, the last remaining steam-powered Mosquito Fleet vessel on Planet Earth.

The Virginia V is a 125-foot long, 24-foot wide, steam-powered vessel made of old growth, locally sourced fir, with a 75-inch, 4-bladed propeller. Now, I’m six feet tall – or 72 inches…which means the prop on Virgina V stands even taller than me. Each summer from 1922 through 1970 (with a few interruptions around World War II) Virginia V carried Campfire Girls from Seattle to Camp Sealth on Vashon Island. Thousands of women in the Northwest recall riding on “The Vee” (as she was affectionately called) at the beginning of a camping adventure, and some of them were even aboard the ship when I was narrating and came up afterward to share their memories with me. It was an amazingly authentic way to connect with the history of the ship aboard which we were then riding.

Back in 1910, farmers and business people along Colvos Passage in Kitsap County and on the west side of Vashon Island were unhappy with the unreliable boat service they received, so Captain “Nels” Christensen and John Holm formed the West Pass Transportation Company and purchased a boat called the Virginia Merrill, a 54-foot long gasoline-powered tug. her name was shortened to simply Virginia and the ship was converted for use as a small ferry. Virginia was replaced two years later when they purchased a bigger ship, dubbed the Virginia II, a 77-footer powered by a gas engine. In 1914 the company purchased a 92-foot steam ship named Typhoon and renamed her Virginia III. In 1918 they purchased a 98-foot steam ship named Tyrus and renamed her Virginia IV.

Then, in 1921, the West Pass Transportation Company contracted with Anderson & Company of Maplewood, Washington, in Pierce County, to begin construction of the Virginia V. The steam engine from Virginia IV was removed and reinstalled in Virginia V before her launch on March 9 of 1922. On June 11 of that year, Virginia V made her maiden voyage from Elliott Bay in Seattle to Tacoma down the West Pass. She continued to make this voyage nearly every day until 1938.

The advent of the automobile is what effectively ended the era of the Mosquito Fleet. According to HistoryLink, roughly 40 percent of the once vast armada ended up either abandoned, burned, dismantled, exploded, re-engined, relocated, sunk, salvaged, scuttled, or wrecked. By 2021, only two Mosquito Fleet vessels still existed. The Virginia V, now listed on the National Register of Historical Places, is owned and maintained by the Virginia V Foundation and spends her days docked at Historic Ship’s Wharf on South Lake Union in Seattle.

The other surviving Mosquito Fleet vessel is the Carlisle II, a 65-foot diesel-powered passenger-only ferry built in 1917 and owned by Kitsap County that has operated between Bremerton and Port Orchard since 1936.