The Whitman Massacre

Marcus and Narcissa Whitman were Christian missionaries who left their homes in upstate New York and traveled with another missionary couple, Henry and Eliza Spalding, to what was then called Oregon Country in 1836. Their mission? To “Christianize” Indians.

In fact, Oregon wasn’t even a territory yet. The United States government didn’t have any programs in Oregon Country, which at the time consisted of the present-day states of Washington, Oregon, Idaho, and parts of Wyoming and Montana. The Whitmans and the Spaldings were among the very first Americans of European decent to travel across North America by land to the western part of Oregon Country.

Lewis and Clark had only just done it thirty years earlier, and there had been fur traders, trappers, and others of various nationalities in the area for a few years. But the Whitmans and the Spaldings were the first to settle in Cayuse and Nez Perce Indian territory near today’s fashionable wine destination of Walla Walla, Washington.

Eleven years after the Whitmans arrived, a group of Cayuse ambushed and killed them along with eleven other people in what became a pivotal event in Washington state and Pacific Northwest history called The Whitman Massacre, but the story you might think you know may very well be appended – or upended – or both by the time this article is finished.

The story of Marcus and Narcissa Whitman has been told and retold so many times in classrooms throughout American history that it can be difficult to separate fact from fiction. But a new book coming out this month from Seattle’s own Sasquatch Books aims to do just that. It’s called Unsettled Ground: The Whitman Massacre and Its Shifting Legacy in the American West, authored by Cassandra Tate, a Seattle-based writer and editor. A former journalist, she earned a Ph.D. in American History at the University of Washington in 1995 and has contributed more than 200 articles to one of our favorite websites, HistoryLink.org, the online encyclopedia of Washington State history.

For those of you who have no idea what the Whitman Massacre is or how its effects have rippled across time to lap against the shores of modern day discourse, the following is an abridged version.

Prior to 1803, the United States didn’t even stretch halfway across North America. Thomas Jefferson purchased the Louisiana Territory from France, essentially expanding America two-thirds of the way west toward the Pacific. He then sent Lewis and Clark and the Corps of Discovery to go check out the new purchase, which they did and came back with fantastic tales of strange creatures, harrowing landscapes, and tribal indigenous peoples.

A few years later, a wave of religious revivalism called the Second Great Awakening swept across the east coast, including a particular hotspot in western and central New York state called the “Burned-over District.” It was so named because of the highly publicized revivals that crisscrossed the region to such a great extent that spiritual fervor seemed to set the area on fire. Caught up in this fervor were a young Marcus Whitman and Narcissa Prentiss.

Marcus dreamed of becoming a minister but did not have the money for such schooling. He studied medicine for two years with an experienced physician and received his medical degree from Fairfield Medical College in New York. He practiced medicine for a few years in Canada but was interested in going west. In 1835, Whitman traveled with the missionary Samuel Parker – who eventually introduced him to Narcissa – to present-day northwestern Montana and northern Idaho, to minister to bands of the Flathead and Nez Perce nations. During this journey, he treated several fur trappers during an outbreak of cholera. At the end of their stay, he promised the Nez Perce that he would return with other missionaries and teachers to live with them.

Narcissa was a primary school teacher in Prattsburgh, New York, but like many young women of the era, she became caught up in the Second Great Awakening as well. She decided that her true calling was to become a missionary, but she wasn’t allowed to do so as a single woman. After applying for missionary service, she met and married Dr. Marcus Whitman on February 18, 1836. The two were sponsored by the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions, and – along with fellow missionaries Henry and Eliza Spalding – became some of the first Americans to travel overland on what would become the Oregon Trail to what would become the Pacific Northwestern United States.

The Spaldings decided to establish their mission on Nez Perce land at a place called Lapwai near present-day Lewiston, Idaho. The Whitmans headed a bit farther west and established their mission at a place called Waiilatpu, near present-day Walla Walla, Washington. Why didn’t the two couples band together to establish a joint mission where there would be safety in numbers, you might ask? Well after eight months of overland travel, spending every single day and night with the same people with their same annoying personality quirks and their same uncomfortable demeanors…the two couples were right sick of each other! If they hadn’t separated upon arrival, I’d say there’s a chance they may have eventually massacred each other.

When the Spaldings built their mission for the Nez Perce, they also established the first European-American home in what is today the state of Idaho. They were also responsible for bringing the first printing press into the territory, and were generally successful in their interactions with the Nez Perce, baptizing several of their leaders and teaching tribal members. Henry developed an appropriate written script for the Nez Perce language, and translated parts of the Bible, including the entire book of Matthew, for the use of his congregation.

Eliza Spalding was very well liked by the Nez Perce peoples, whose women often followed her around her home wanting to see how the she cooked, cleaned, dressed, and cared for her children. She was quickly liked by them and respected for her courage and for her attempts to act as a buffer between the Nez Perce and Henry, who was not always as well liked. He was inflexible on gambling, liquor, and polygamy and even went as far as whipping some Nez Perce or having them whip each other. Henry seemed to be the opposite of Eliza in his relationship with the Nez Perce; where she sought to understand them, he sought for them to understand him.

The Whitman settlement was in the territory of both the Cayuse and the Nez Perce tribes. Marcus farmed and provided medical care, while Narcissa set up a school for the Indian children. However, their relationships with the natives soon soured to the point where both Marcus and Narcissa eventually abandoned their goal of trying to convert them to Christianity and instead focused on assisting overland travelers on their way to the Willamette Valley at the end of the Oregon Trail.

Marcus continued to treat patients, both American and Indian, but the influx of settlers in the territory brought new infectious diseases to the Indian Tribes, including a severe epidemic of measles in 1847. The lack of immunity to Eurasian diseases resulted in high death rates for the indigenous peoples, with children especially dying in large numbers. The Whitmans cared for both Cayuse and settlers, but half of the Cayuse died including nearly all the Cayuse children. Seeing that more settlers had survived, the Cayuse suspected the Whitmans were to blame for the devastating deaths among their people.

The Cayuse tradition held that medicine men were personally responsible for the patient’s recovery. Their despair at the deaths, especially of their children, among a number of other misunderstandings and hurt feelings, culminated with a number of Cayuse ambushing the settlers at the mission and killing both Marcus and Narcissa, as well as eleven other people living there on November 29, 1847. Cayuse warriors destroyed many of the buildings at Waiilatpu and held another 45 or so women and children captive for a month before releasing them after negotiations. Some of the Cayuse men took captive women to be their “wives” and there is at least one account of rape occuring at the hands of these men. This event became known to Americans as the Whitman Massacre, and it triggered the larger conflict that became known to non-Indians as the Cayuse War.

It’s important to note, at this point, that the reasons behind the killings and the conflict are different, depending on which perspective you take. From the standpoint of the Americans, these poor missionaries were simply trying to save the souls of the heathens and for their efforts they were slaughtered. From the Cayuse standpoint, the Americans had broken a number of promises and brought with them diseases that literally wiped out nearly their entire population. The only way to put an end to the unimaginable suffering they were experiencing was to wipe out the Americans first.

The old expression, “To the victor go the spoils,” is generally accepted as accurate based on who gets to write the corresponding history of any conflict. The growing number of American settlers, with their advanced technology, tipped the population balance in their favor. The hunt for the Indians who participated in the massacre resulted in the eventual hanging of five Indian “perpetrators” – which I put in quotes because there’s conflicting evidence that those five men were even the same ones who participated in the killings. But somebody had to hang for it…and these men paid the price.

Retellings of the harrowing events became more and more grandiose as the years passed. Even eyewitnesses were known to exaggerate their stories for shock value. In time, even the reasons behind key events were clouded by myth and convenience – such as the notion that “Marcus Whitman saved Oregon” by traveling to the nation’s capitol and single-handedly convincing lawmakers to establish the Oregon Territory…something that was almost entirely fabricated. After their deaths, the Whitmans became martyrs to the American cause of Manifest Destiny and their legends only grew in size as well as historical inaccuracy.

Then, in the 1970s, Americans began reexamining the stories about Indians and realizing that many of the events once considered “facts” were more likely a result of fanciful fiction that had gone unquestioned. Because of the conflicting perspectives, what became known as a “massacre” was eventually referred to as a “tragedy.” What was once called a “war” evolved into a “conflict.” And some of the “battles” with Indians (some of whom were women and children) may have really been closer to one-sided revenge killings. Our ever-changing understanding of past events has brought some balance back to the Whitman story…but has the pendulum swung far enough? And is it in danger of swinging too far in the opposite direction, unfairly vilifying the Americans?

These are some of the significant questions that Dr. Cassandra Tate’s book, Unsettled Ground: The Whitman Massacre and its Shifting Legacy in the American West, tries to address, as you can hear in the podcast interview:

Podcast: Play in new window | Download | Embed

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | RSS | More

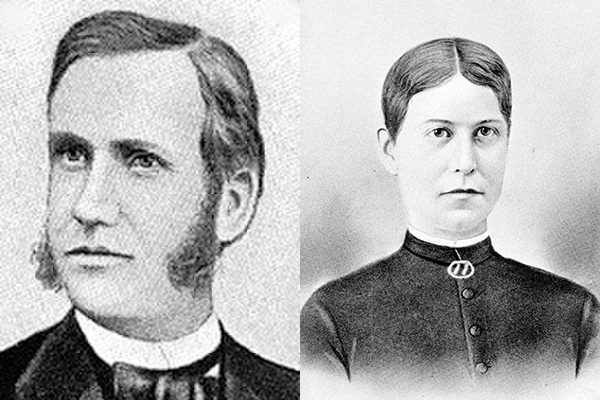

Some of the best evidence of how the Whitman legend evolved over time can be seen in pictures of Marcus and Narcissa themselves. Search Google for pictures of the martyred missionaries, and you’ll pull up three distinct sets of images. The first are illustrations published in an 1895 book by Chicago newspaperman Oliver Nixon called How Marcus Whitman Saved Oregon.

The picture captioned “Doctor Marcus Whitman at the time of his marriage” featured a ministerial looking man with neatly parted hair wearing the collar favored by Presbyterian clergymen in the late 19th century. Whitman, of course, was not an ordained minister. Although he aspired to the ministry, he couldn’t afford the time or education necessary to attain that. And this is a little disturbing fact…it was actually a lot easier to become a medical doctor that it was a preacher at that time in history.

The picture identified in Nixon’s book as Mrs. Narcissa Prentiss Whitman – Prentiss being her maiden name – is of a rather stern looking woman with a thin, downturned mouth and narrow, straight eyebrows. She’s wearing a top buttoned right up to her throat and her hair is also neatly parted and pressed. These are very nice-looking representations of American citizens in the mid-19th century…but they are not, it was later learned, actually images of Marcus and Narcissa.

In subsequent editions of the book, Nixon admitted that the photograph of Marcus Whitman was not Marcus Whitman the missionary but Reverend Marcus Whitman Montgomery…a Chicago clergyman totally unrelated to the pioneer other than being named after him. The image was retouched to remove the clerical collar and tidy up the sideburns a bit, and the caption was changed to read, “No picture of Dr. Whitman is in existence. The above portrait is made from the basis of a photograph of Reverend Marcus Whitman Montgomery, who resembled Dr. Whitman very closely. Changes have been made under the supervision of the family who now pronounce this a very correct likeness.“

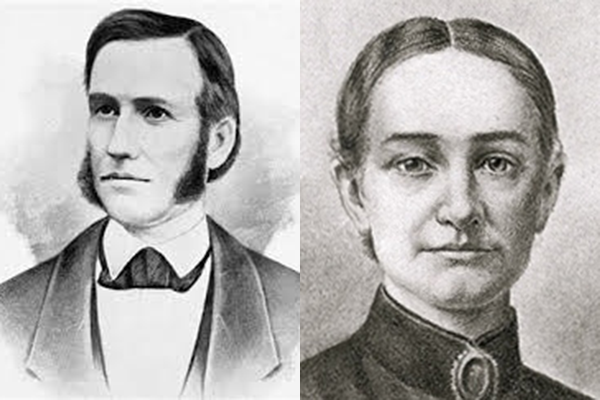

As for Narcissa, Nixon replaced the original photo with a drawing of a much softer-looking woman with large, expressive eyes. She’s gazing directly at the viewer with her mouth slightly upturned at the corners, and her parted hair isn’t pulled back as tight. The caption beneath this entirely new picture reads, “No authentic picture of Mrs. Whitman is in existence. This portrait of her has been drawn under the supervision of a gentleman familiar with her appearance and with suggestions from members of her family. It is considered a good likeness of her.“

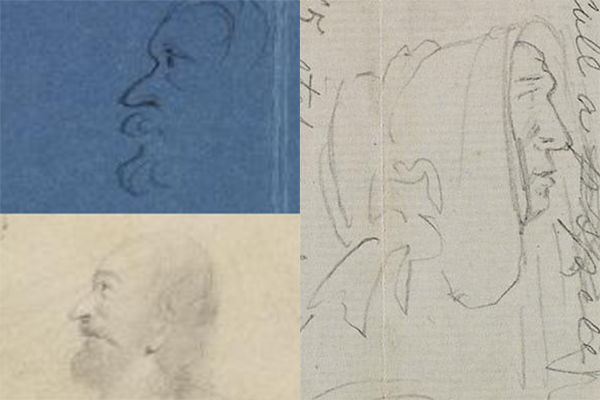

A third set of images come from sketches made by Paul Kane, a Canadian artist who visited the Whitman mission in July, 1847, just four months before the attack. The sketch that ended up coming to represent Narcissa shows a woman seated outdoors without a sunbonnet, freely flowing curled locks, and a scoop-necked dress with her sleeves pushed up to the elbows. Kane’s sketch that came to represent Marcus Whitman depicts a man wearing a fringed, buckskin jacket and a frontier-style hat. He may even be sporting some Van Dyke-style facial hair.

Dr. Tate notes how interesting it is that these images were chosen to represent the Whitmans. Paul Kane spent years sketching the indigenous peoples of western North America, and his portfolio of sketches at the Royal Ontario Museum includes just 12 images of obviously Caucasian men and about five of Caucasian women. Narcissa would never have likely appeared in a low-necked dress…in fact, her own adopted daughter described her as someone who dressed “severely.” Also, she was rarely caught without a sunbonnet outside and was not known to expose her arms in public.

Her husband, by comparison, was also known to dress more formally and was loathe to wear the garb of the quote-unquote “heathens” that he had come west to save. After his death, his possessions were inventoried and nary a buckskin jacket was found. What WAS found was described by fellow missionary Henry Spalding as a “superfine” jacket, silk vest, and other clothing items worth more than $10,000 in today’s dollars.

Of Paul Kane’s Caucasian sketches, one woman IS wearing a sunbonnet and her face appears very weathered and homely. One man in Kane’s sketches is fully bearded, balding and looking quite unheroic. Could these have been the real depictions of Marcus and Narcissa Whitman? If so, how interesting is it that the trajectory of the Whitman mythology could have changed if the picture of the haggard woman and unshaven man had been selected as authentic instead of the more pleasing images that better fit the narrative.

Perhaps we’d be having a very different discussion today…or perhaps there wouldn’t be a need for a discussion about this tragedy at all.

I have to say, after reading Dr. Tate’s book, my opinion on the Whitman statue in Olympia has changed. Prior to this, I was adamantly opposed to legislative calls to remove the statue. But upon reflection, I think what I was (and am) really opposed to is the diminishing of what the statue is supposed to represent. The fictionalized caricature of a muscly Marcus Whitman is not Marcus Whitman the man. That’s Marcus Whitman the legend…a legend that does not and never existed.

For that reason, it’s time to consider removing the statue. But that does not supplant the need to recognize the fortitude, endurance, and determination of those first American settlers. Those, too, are admirable qualities, without which we would not have the great state that we all know and love today. History has room for multiple stories, and it’s imperative that we tell all of them – not just the ones we happen to like today – in order to get the whole picture.

Great article, but I would have loved to hear more about how this led into the Cayuse War.

Since we’re splitting hairs here, your e-mail address is missing a “t” as well.

Eleven years after they arrived, a group of Cayuse ambushed and killed the Whitmans and eleven other people in what became a pivotal event in Washington state and Pacific ….

This is a misplaced modifier. The Whitmans had arrived 11 years earlier, not the Cayuses.

Pingback: Whitman Mission… | Chaos Leaves Town