The deadliest bridge collapse in Washington State history

On Wednesday, January 3rd, 1923, Cowlitz County Commissioner-elect Benjamin Barr sat in the back seat of his vehicle, when his driver – Arleigh Millard – felt an unsettling shudder through the springs in his seat. Miller glanced nervously at Barr through the rear-view mirror, unable to move the vehicle forward. The pair were stuck atop the Allen Street Bridge here in Kelso, Washington, when seconds later it all came crashing down, resulting in the deadliest bridge collapse in Washington State History.

This story begins at the Cowlitz County Historical Museum which is just blocks away from the site of the 1923 bridge disaster. Kelso is a medium-sized city in Washington that has its roots in the timber and fishing industries. Platted by a Scottish surveyor in 1884 and named for his home town in Scotland, Kelso incorporated in 1889 – the same year Washington became a state.

Courtesy of the Cowlitz County Historical Museum.

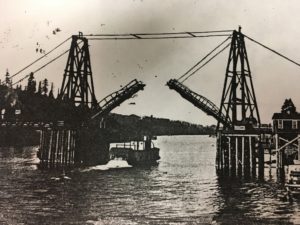

By 1904, the people were ready for the first bridge Long-Bell Lumber Companyover the Cowlitz River. Unfortunately, it collapsed two years later after heavy rains. So they built a second bridge with a draw span entirely out of wood and metal cables. That opened in 1907. River traffic up and down the Cowlitz necessitated a drawbridge, which meant tall towers had to be constructed on either side to hold the counterweights used to lift the bridge.

Almost 10 years later, the effects of weathering and daily use required the Allen Street Bridge be renovated in 1915. But instead of replacing old timbers with new ones, city officials decided just to lay down new ones on top of the old, nearly doubling the weight of the draw spans. After a particularly brutal storm in December 1922, the Cowlitz river had swelled to flood levels. The stage had been set for the deadliest bridge collapse in state history to unfold.

Flooding was nothing new to the people of Cowlitz County. Their rivers overflowed their banks in 1867, 1894, and would flood again in 1933, 1948 and 2006. Since the December storm had dislodged so much material upstream, all that timber came rushing down the Cowlitz River, further weakening the bridge that some were already too scared to cross.

Courtesy of the Cowlitz County Historical Museum.

As the logjam piled up in the first weeks of the new year, workers started returning to the lumber mills after the holiday. Many of these workers were transients – though not by today’s definition. In the early part of the last century, transients would travel from town to town in search of whatever work they could find.

Most of the folks on the bridge that day were coming home from their jobs at the Long-Bell Lumber Company just on the other side of the river. There was a traffic backup due to a stalled car on one end and a team of horses on the other, so all of the cars started to pile up, and that was too much for the bridge to handle.

Survivors of the disaster reported hearing a series of loud, metallic pops as the twisted cables – straining under the weight – began to fail…snapping and viciously recoiling one by one. The good news is that pedestrians on the bridge heard the horrifying sound and barely had time to scramble to safety. The bad news is that everyone trapped in their vehicles didn’t stand a chance.

When the bottom of the deck collapsed from underneath the Allen Street Bridge, it sent hundreds of people and cars and horses into the water. Those who weren’t able to escape immediately were likely sunk in their cars, never to see the light of day again. As the draw span fell, it pulled the support towers down with it, raining tons of wood and metal down on top of those struggling to get out of their cars. Almost immediately, nearby boats – like the steamer Pomona and a half-dozen others – realized what was happening and cast off, hoping to save whoever they could. Pomona itself pulled out 40. Who knows how many other lives were saved?

One life that notably remained in question was that of Benjamin Barr. Though the Pomona and other boats pulled out dozens and dozens of people who surfaced after the collapse, Barr couldn’t be located in the hours following the disaster. The search for Benjamin Barr went on for days. They even repeatedly published his name in the paper, looking for any sign of the commissioner-elect.

Courtesy of the Cowlitz County Historical Museum.

I went looking for any historical trace of Benjamin Barr, and the obvious place to look was at the Cowlitz County Historical Museum. But after coming up empty, I walked the few short blocks to the site of the original disaster, hopping over a few busy train tracks that carry both freight and passengers on a fairly regular basis. Just on the other side was my destination.

Today, you can actually walk a trail along the side of the Cowlitz river, in between the railroad tracks and the river itself. Almost nothing remains of the bridge that collapsed in 1923 and killed some 20 people. In fact, if you visit Kelso today, all you’re going to find is the bridge that’s currently over the river. There’s really not much left except a little bit of debris. But occasionally you can find something intriguing. I found a square nail that might have been used to hold the entirely wooden bridge together. And when it collapsed, a lot of it went right to the bottom of the river.

Courtesy of the Cowlitz County Historical Museum.

Rescue efforts lasted throughout the night and around the clock for the next several days, until it became clear that volunteers were no longer looking for survivors. Their frantic searching had turned into a recovery effort. Since the bridge intended to replace the ill-fated wooden span was still under construction just next to the collapsed bridge, crews quickly turned it into a makeshift platform. They began using cranes to haul out cars, cables and mangled pieces of wreckage from the river bottom.

In the weeks to follow, there still wasn’t an official count of the number of people who lost their lives. Because of the winter storm, the visibility underwater was close to nothing. Still, city officials sent in divers to try and recover bodies. When that effort failed, they dynamited a three-mile stretch of riverbed, hoping it would dislodge any bodies still stuck in the wreckage. The last body found didn’t surface until six months later, along the banks of the Columbia River, more than three miles away from where the Allen Street Bridge once stood.

The landing in the foreground is all that remains of the steel span bridge constructed after the collapse.

When the cleanup ended, the third bridge – known as the steel span – was finished quickly to restore the flow of traffic. It stood quietly and unassumingly for almost 80 years, until it was replaced in 2000 by today’s bridge that covers both the river and the railroad. A sign affixed to a concrete platform by the Kelso Rotary says “Rotary Landing,” but in fact it’s not a landing at all. It’s all that remains of the steel bridge over the Cowlitz river.

As I headed back toward the museum, I decided to swing by the Cowlitz County headquarters just a few blocks away. Steeped in history, it’s an impressive testament to local government. Commissioner-elect Barr never got to serve his term in office as his body was never found. If he had lived, he would have spent his days at the Cowlitz County courthouse, which was also built in 1923 on land donated to the county by the City of Kelso.

Back at the museum, I never did find a photo or official record of Benjamin Barr. But staff there helped me locate hundreds of photos and news articles about the deadliest bridge collapse in Washington State History. There’s even an oral history recording made in the early 1980’s of an interview with a doctor who treated the injured pulled from the river that fateful day. It’s a fascinating story of hope and heartbreak and an amazingly authentic window into the history of Washington State.

There’s a lot more you can learn at the Cowlitz County Historical Museum. If you’re ever in Kelso, I suggest you stop by and take a look for yourself. They’re open Tuesday through Saturday, 10-4, and admission is free.

Pingback: Archives spotlight: Historical weather – From Our Corner