Pateros will rebuild. They’ve done it before.

And so have Brewster, Twisp, Malott, and Methow, just to name a few of the resilient communities within north-central Washington.

And so have Brewster, Twisp, Malott, and Methow, just to name a few of the resilient communities within north-central Washington.

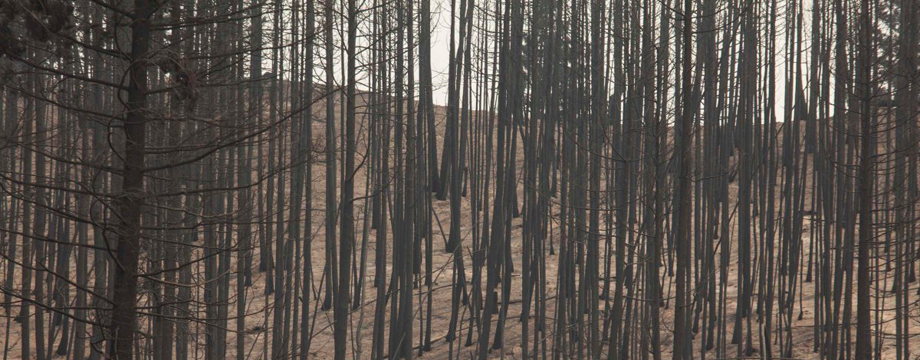

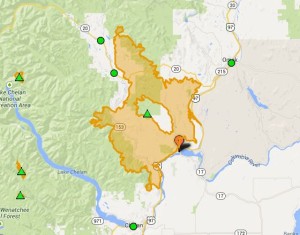

As the Carlton Complex of fires continues to ravage the dry, rolling hills along the Columbia and Okanogan Rivers between Wenatchee and Omak, it can be easy to succumb to the notion that all is lost forever in the wasteland that is still only 50-percent contained. However, these communities of stalwart, rural Washingtonians are accustomed to facing and overcoming challenges and depend on each other for survival.

The lightning-sparked series of wildfires in Washington have already burned about 400 square miles (or more than 250,000 acres) making this the largest wildfire in state history – surpassing the Yacolt Burn, which consumed 238,920 acres in southwestern Washington and killed 38 people in 1902.

As of the writing of this article, only one death has been blamed on the Carlton Complex fires – a man who suffered a heart attack while protecting his home from the encroaching blaze. More than 300 homes have been destroyed and hundreds of livestock have either burned to death or suffocated.

As of the writing of this article, only one death has been blamed on the Carlton Complex fires – a man who suffered a heart attack while protecting his home from the encroaching blaze. More than 300 homes have been destroyed and hundreds of livestock have either burned to death or suffocated.

Writing from the safety of western Washington and far from the havoc taking place only a few hundred miles east, the image of Pateros’ iconic billboard being eaten by flames brought the reality of what is happening in our state crashing down.

Pateros has been a river stop along the Columbia since our territorial days and is no stranger to environmental mishap. Around 1885, Lee Ives headed north from Ellensburg to Wenatchee – then only a small store – where he loaded up his horses with goods. Meeting trappers and Native Americans at the junction of the Methow and Columbia Rivers, Ives built several buildings that became the first road house with a small store on the banks of the Columbia River. It was known as Ives Landing.

Pateros has been a river stop along the Columbia since our territorial days and is no stranger to environmental mishap. Around 1885, Lee Ives headed north from Ellensburg to Wenatchee – then only a small store – where he loaded up his horses with goods. Meeting trappers and Native Americans at the junction of the Methow and Columbia Rivers, Ives built several buildings that became the first road house with a small store on the banks of the Columbia River. It was known as Ives Landing.

In 1889 – the year Washington became a state – an early and deep snowfall caught residents off guard. Finding no grass to graze upon, much of the cattle starved to death which created an economic crisis for residents as well as a threat to their food supply.

Five years later, a long spring that suddenly became summer caused the season’s snowpack to melt rapidly, flooding the town and causing a great deal of property damage and lives lost. Ives and his wife had to temporarily relocate their shop and recently-built hotel to higher ground as the Columbia River reached 70 feet above its low water mark.

1894 was also known as the year of the crickets at Ives Landing – which officially became known as Pateros in 1900. The receding floodwaters had left ideal breeding grounds and the nymphs began devouring everything in sight. Omnivorous scavengers, the crickets fed on decaying plants, fungi, seedling plants, and even their own dead when no other sources of food were available.

North-central Washington suffered an 11-year drought around 1915-16 and average yearly precipitation dropped to about five inches a year. Residents were forced to find other means to sustain their livelihoods that didn’t depend on agriculture for more than a decade.

North-central Washington suffered an 11-year drought around 1915-16 and average yearly precipitation dropped to about five inches a year. Residents were forced to find other means to sustain their livelihoods that didn’t depend on agriculture for more than a decade.

Throughout their history, residents of Pateros have endured what could arguably rise to the level of biblical plagues…insects, floods, famine, and more. Time after time, they have rallied together as a community to rebuild. In the modern era of a global community, Pateros – along with other Washington towns and cities devastated by wildfire – will rebuild with the help of every Washingtonian as well as with federal assistance.

No longer are we a series of isolated hamlets scattered across the beautiful Pacific Northwest. Every resident of Washington State should consider Pateros residents to be their neighbors. And we can help.

Donate directly to the front line defenses by visiting the Okanogan County Department of Emergency Management’s website or the Chelan County Emergency Management’s Facebook page. For the latest developments on the Carlton Complex fires, visit carltoncomplex.blogspot.com.