LeRoy Tipton’s take on local lodge history

I introduced myself and my wife to our Lake Quinault coach tour guide, LeRoy Tipton. He said our names twice and quipped, “I have a really good memory. But my recall does not work very well. In fact, I have a very good memory except for names…faces, places, events, dates…stuff like that.”

I introduced myself and my wife to our Lake Quinault coach tour guide, LeRoy Tipton. He said our names twice and quipped, “I have a really good memory. But my recall does not work very well. In fact, I have a very good memory except for names…faces, places, events, dates…stuff like that.”

During the twenty-minute introduction where LeRoy (pronounced “luh-ROY” not “LEE-roy”) eloquently set the stage for our three-hour tour of the Olympic National Park, we would find that he often employed his dry but wonderful sense of humor. He began by quizzing the group on the gender of the massive Roosevelt Elk head that hung over the lodge’s historic fireplace.

“Can anyone tell me if that is a bull, which is a male, or if it is a cow, which is a female? Those of you who said cow, you are correct…but wait, who said bull? You are correct as well because it is a cow-bull (or a bull-cow, I’m not really sure what the difference is). But you see, God didn’t create that animal, a taxidermist did. Because a bull Roosevelt Elk’s head is too large and heavy to put over the fireplace, the taxidermist put the antlers of a bull elk on the head of a cow.”

“Can anyone tell me if that is a bull, which is a male, or if it is a cow, which is a female? Those of you who said cow, you are correct…but wait, who said bull? You are correct as well because it is a cow-bull (or a bull-cow, I’m not really sure what the difference is). But you see, God didn’t create that animal, a taxidermist did. Because a bull Roosevelt Elk’s head is too large and heavy to put over the fireplace, the taxidermist put the antlers of a bull elk on the head of a cow.”

The information LeRoy shared with us from that point on only got more and more interesting:

The Quinault Indian Nation owns the lake itself, and its shores were their summer dwelling place for centuries. During the winter months they lived in cedar homes along the ocean, some 33 miles away from the lake. It’s milder at the lake than it is at the ocean, but the average rainfall at Lake Quinault is 144 inches (12 feet). Just to compare that, the Hoh rainforest gets about 90 inches (7.5 feet) of rain each year.

The Lake Quinault Lodge as it stands today was built in 1926, but by 1892 there already was a structure at that location called the Log Cabin Hotel or simply, “the old lodge.” The Olympic Mountains were first explored in 1890, the same year the first homesteader brought his family into the area. To get to the lake would mean a 10-day hike through the forest from either Montesano or Hoquiam, or you could find an Indian guide in the coastal village of Taholah who would bring you up the Quinault over a two or three-day period.

The Lake Quinault Lodge as it stands today was built in 1926, but by 1892 there already was a structure at that location called the Log Cabin Hotel or simply, “the old lodge.” The Olympic Mountains were first explored in 1890, the same year the first homesteader brought his family into the area. To get to the lake would mean a 10-day hike through the forest from either Montesano or Hoquiam, or you could find an Indian guide in the coastal village of Taholah who would bring you up the Quinault over a two or three-day period.

By the time any one reached the lake, they were cold, hungry, wet, and tired, and wanted a place to stay. That’s where the old lodge came in. The original owners, the Olson brothers – Elvin, Ignar, Herbert, and two others (who later incorporated as the Olympic Recreation Company) – sold the hotel to a woman by the name of Olena Egge.

In August of 1924, she took her family on a picnic across the fog-covered lake and up to the summit of Higley Peak. While they were up there, Olena noticed a line of black smoke snaking through the sheet of white fog. What she feared the most was happening…and a phone rang at the ranger station near where she and her family were dining.

Imagine the trauma that she must have endured as Olena raced down the mountain and caught a ride back across the lake. But by the time she and her family arrived on the southern shore, nothing but glowing embers remained. In fact, her friend – a woman named Beverly, who was her cook and chambermaid – had perished in the fire, which had started in the flue in the kitchen.

All they were able to salvage from that fire was the fireplace and chimney, an old piano and the hotel safe – which are all still on the property and can be easily viewed and appreciated for their historic value by any of the lodge’s patrons.

All they were able to salvage from that fire was the fireplace and chimney, an old piano and the hotel safe – which are all still on the property and can be easily viewed and appreciated for their historic value by any of the lodge’s patrons.

Word of the fire spread to Seattle, and the typesetter at the local paper – who was getting ready to print the story – recognized a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. “The Quinaults are going to need a hotel,” LeRoy recounted, and that typesetter immediately made the trip to Hoquiam in search of a business partner. He found one in a very successful timber merchant named Ralph Emerson, who coincidentally had just finished building the Hotel Emerson in downtown Hoquiam (which is now a home for seniors and the disabled).

So in 1925, the new business partners took over the Forest Service lease that Olena Egge had been operating under and built a new structure on the site of the former Log Cabin Hotel. It’s now known as “the annex” and accommodates visitors with pets. The original 20-room-plus-kitchen-and-dining-room annex – sometimes called “the boathouse” because of its proximity to the lakeshore – now boasts nine much more comfortable guest rooms. Still Emerson and his partner quickly realized that what they had wasn’t adequate.

“Something was going on in the 1920’s in the United States…anybody remember?” LeRoy asked. I quickly answered, “Prohibition,” which seemed to impress even our knowledgeable tour guide. As it turns out, Emerson proceeded to build a floating dance hall that doubled as an actual boathouse just off shore. And since it was technically on the lake – which remember, belonged to the Quinault Tribe – it was not considered subject to federal liquor laws. Needless to say, there were a great number of “dancers” out at the hotel’s boathouse each night during that period.

“Something was going on in the 1920’s in the United States…anybody remember?” LeRoy asked. I quickly answered, “Prohibition,” which seemed to impress even our knowledgeable tour guide. As it turns out, Emerson proceeded to build a floating dance hall that doubled as an actual boathouse just off shore. And since it was technically on the lake – which remember, belonged to the Quinault Tribe – it was not considered subject to federal liquor laws. Needless to say, there were a great number of “dancers” out at the hotel’s boathouse each night during that period.

Because of the large crowds being drawn to the area, Emerson decided to hire an architect by the name of Robert Reamer who was nationally known for designing the Old Faithful Inn at Yellowstone National Park as well as Many Glacier Hotel at Glacier National Park. His signature designs consisted of lots of wood, big and bold structures and a very masculine style. Emerson and Reamer both agreed to use a construction chief by the name of Roy Garrison – who had a reputation as a real taskmaster who brought in projects on-time and under-budget – to build the lodge itself.

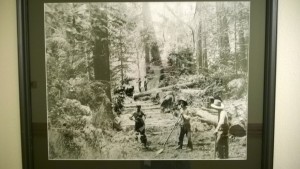

Roy hired 45 of the most competent workers in the area and set them to work two rotating 12-hour shifts. It was known as a “hotbed” system because the day crew slept in beds that had been immediately vacated by the night crew, and vice-versa…hence, the shared beds never had a chance to cool down. They build a temporary mill on the premises and got the logs from the surrounding forest. The men built a bonfire each night to light the construction site, and they kept the small access road that led to the lodge busy night and day with deliveries of equipment, fixtures, food, furniture, and everything else needed to create a spectacular destination.

Roy hired 45 of the most competent workers in the area and set them to work two rotating 12-hour shifts. It was known as a “hotbed” system because the day crew slept in beds that had been immediately vacated by the night crew, and vice-versa…hence, the shared beds never had a chance to cool down. They build a temporary mill on the premises and got the logs from the surrounding forest. The men built a bonfire each night to light the construction site, and they kept the small access road that led to the lodge busy night and day with deliveries of equipment, fixtures, food, furniture, and everything else needed to create a spectacular destination.

One of Roy Garrison’s sons was on the work crew and happened to chronicle the events as they played out. On June 9, 1926, they started with an empty lot. Nineteen days later, the frame of the structure that still stands today had been constructed. A month later, on July 10, the lodge’s exterior was complete and Garrison’s garrison of workers had moved on to shingling the roof. On August 18, 1926…53 days after work began…the complete Lake Quinault Lodge was finished.

A fascinating side note to the story of the lodge’s whirlwind construction is the art that adorns the structure. While the Quinaults and other tribal cultures in the Pacific Northwest have a beautiful array of artistic creations, the interior beams of the Lake Quinault Lodge is actually decorated with traditional Mayan symbols. Bringing in Guatemalan artists from the Yucatan Peninsula in 1926 to decorate the structure was a way of showing off the opulence of the hotel during that period in history.

A fascinating side note to the story of the lodge’s whirlwind construction is the art that adorns the structure. While the Quinaults and other tribal cultures in the Pacific Northwest have a beautiful array of artistic creations, the interior beams of the Lake Quinault Lodge is actually decorated with traditional Mayan symbols. Bringing in Guatemalan artists from the Yucatan Peninsula in 1926 to decorate the structure was a way of showing off the opulence of the hotel during that period in history.

Of course, there have been a few modifications over the years. The original wicker furniture is now supplanted by overstuffed, studded leather chairs and sofas. The roof has been reshingled and rebuilt several times and a number of additions have been constructed to expand the guest capacity. LeRoy speculates that the foundation was likely replaced at some point, and knows that the wiring and plumbing has all been brought into compliance with current building code. But visitors to the Lake Quinault Lodge can still stand in the main lobby today and experience the same view that Emerson, Reamer and Garrison did on the day they completed their work.

Great supplemental information to the blog post, Charles, thank you!

Great history here. Thank you!

Strangely, though, the typesetter at the Seattle newspaper who realized the need for a new hotel on lake Quinault after the Log Cabin.Hotel burned, is not Identified by name. He was Frank L. McNeil and he played a very important role in the creation of the Lake Quinault Lodge. He had previously owned and operated the Lehman Hot Springs Resort in Oregon for ten years.

After coming up with the idea for a new hotel, McNeil, as you say, went from Seattle to Hoquiam to find a business partner to build it. He found wealthy timberman Ralph Emerson. Architect Robert Reamer was engaged to design the hotel. You tell that all so well, but I’ll add that Frank McNeil stayed and managed the LQL for 13 years. He died in Quinault (1950, age 75) and is buried there.

McNeil is my father’s great uncle, but Dad always called him Uncle Frank. He’s well-known in our family lore because we always heard about Dad meeting Mom – working at the lodge one summer after high school – when he rowed across the lake to get his mail at Quinault and went to the lodge to visit his Uncle Frank, which he did regularly, I have records and newspaper articles documenting this, if you’re interested.

LQL was constructed at a cost of $100,000. Formal grand opening of the “Finest Resort Hotel in the NW” was Aug. 18, 1926. Dinner, music and dancing – $2.50 a plate. Around 400 from around the PacNW attended, all of whose names were printed in the newspaper.