Of Pork and Politics: Washington in the Pig War

We’re all familiar with the historic events that led to the American Revolution, when the American Colonies seceded from rule by Great Britain. Somewhat less well known are the reasons behind the second war between England and the U.S…the War of 1812. But it’s unlikely you can find very many people who can tell you about the third war between these two superpowers, which took place – or, more accurately, almost took place – in the San Juan Islands in 1859.

This is the story of The Pig War, otherwise known as The Bloodless War or The War That Wasn’t.

It’s important, I think, in order to fully understand the motives behind the events that are to follow, that one be familiar with the players in this worldwide saga that unfolded off of Washington’s coast just prior to the American Civil War. It was a time in America when tensions were running high. The rift between the northern and southern states in the fragile union was being strained daily and many folks were ready to see their infant country divided in two. Through this contextual lens we can better understand how The Pig War came to pass.

The Americans

Democrat

15th President

Served 1857-1861

To begin with, let’s introduce the home team. First up is Democratic President James Buchanan, who had long been criticized for adhering to a “peace at any price” policy dealing with the northern states and the southern states. However, he likely was doing what he thought best for the young country and was under a great deal of pressure to keep the pot from boiling over on his watch.

So imagine how blindsided he must have been when he got a report one morning stating that an international crisis was about to erupt almost 3,000 miles away on the Pacific Coast. Unfortunately for him, the New York Herald ran a story about the dispute – causing him to sternly instruct his military commanders in the region to avoid any precipitous action.

Extreme imbecile

Key to the Pig War mystery

Also unfortunately for Buchanan was the fact that Brigadier General William S. Harney was that military commander. Here’s a little about General Harney’s background:

In 1834, Harney was charged with the possible death of a female slave named Hannah by whipping her to death over the theft of some keys. The story was reported in the Cincinnati Journal, calling Harney “a monster!” Shortly after, Harney moved to Virginia to avoid capture by mob of citizens who were outraged by Hannah’s death.

During Mexican-American War in the late 1840s, Harney raised a few companies of volunteers under the pretext of attacking Indians in Texas. He then proceeded to invade Mexico without orders – against the directive of General Winfield Scott.

- Cut off by Mexican defenses, Harney retreated…losing several men and boosting the morale of the Mexican Army.

- Generals Zachary Taylor and John Wool cited Harney’s “extreme imbecility and manifest incapacity” in official correspondence.

- General Scott orderd Harney to turn over his command. Harney refused and was court martialed.

- In a later battle, Harney grotesquely inflated the number of Mexican soldiers he’d defeated, reporting upwards of 2,000 dead when the actual number was closer to just 150.

- During the battle for Mexico City, Harney was tasked with executing a number of American deserters. He devised an unusual method of dispatching them by putting them all in a wagon under a gallows with ropes around their necks, and forced them to watch the battle until a final flag was raised over the capitol. When the stars and stripes was hoisted up (coincidentally by Capt. George Pickett), Harney gave the order and the wagons were driven out from under the deserters, leaving them dangling in the air strangling to death.

Harney was also well-known for treating junior officers with terrible contempt. By 1859, at least two had been court martialed, one resigned and one was a fugitive after having been so enraged by Harney that he drew his pistol on the General.

And now this is the man calling all the shots in the region.

Graduated last of 59 cadets in the US Military Academy class of 1846

The man Harney tapped to carry out his irresponsible actions in the San Juans was none other than Captain George Pickett, who – upon hearing of the situation – famously declared, “We’ll make a Bunker Hill of it!“

This is clearly not a man looking to avoid a potential war.

Near the beginning of the American Civil War, Pickett – born in Richmond, Virginia – enlisted in the Confederate Army, attaining the rank of brigadier general. He is best known for two things…his ruthless treatment of Confederate deserters (he executed at least 20 of them during the Civil War) and the famously failed attack on Union troops during the Battle of Gettysburg – now known as Pickett’s Charge.

After the Civil War he fled to Canada for a number of years until President Grant let him return without fear of retribution.

Longest active-duty service in American history

The man tasked with bringing the escalating situation in the San Juans under control was Old Fuss and Feathers himself…General Winfield Scott, hero of the War of 1812, The Indian Wars, The Mexican-American War, The Civil War and a number of smaller skirmishes. Scott was also the unsuccessful presidential candidate of the Whig Party in 1852. At six feet five inches in height, he remains the tallest man ever nominated by a major party. Scott lost to Democrat Franklin Pierce in the general election, but remained a popular national figure.

President Buchanan knew that if anyone could defuse a potential war with Great Britain over a pig on the other side of the continent it was the man who earned his nickname for his insistence on military bearing, courtesy, appearance and discipline.

First territorial governor of WA

Superintendent of Indian Affairs

Central Washington University Professor Kent Richards wrote of Isaac Stevens that he was a man either loved or hated, but seldom ignored. A firm supporter of Franklin Pierce’s candidacy for President of the United States in 1852, Stevens was rewarded by President Pierce on March 17, 1853, by being named governor of the newly created Washington Territory.

However you feel about the man who “negotiated” the treaties that put Native Americans onto reservations in Washington – which ultimately led to the Indian Wars of the mid 1850s – few could argue that he was just trying to carry out his orders to the best of his knowledge and abilities.

Although sometimes thought of as a hothead, he acted with commendable restraint in the matter of the San Juan dispute – agreeing to “abstain from all acts on disputed grounds which are calculated to provoke any conflicts.”

Enjoyed potatoes, possibly with a side of bacon

Not much is known about the man who caused the only fatality in the Pig War, but Lyman Cutlar left Kentucky with dreams of striking it rich in the Gold Rush of 1849. Those dreams, however, never did materialize. Lyman had heard that San Juan Island was a part of the United States, so the failed prospector decided to quit the Gold Rush altogether.

Under the Donation Land Claim Act of 1850, any white male citizen over 21 years of age was entitled to 160 free acres, so Cutlar staked his claim on the island. By April of 1859, he had a small cabin and enough land with rich topsoil for a nice potato patch. His cabin also happened to be the nearest, geographically, to the Hudson’s Bay Company livestock ranch.

The British

Member of the Order of the Bath, an order founded in 1725

Our first Englishman in this story is Colonial Governor James Douglas. He spent nineteen years working in Fort Vancouver, and served as a Clerk until 1835, when he was promoted to Chief Trader. Four years later he was promoted to Chief Factor, the highest rank in the HBC.

In 1849 Britain leased the entirety of Vancouver Island to the HBC under the condition that a colony be created. Douglas moved the headquarters of the western portion of the Company from Fort Vancouver to Fort Victoria, eventually leaving his position with the HBC to become Governor of the Colony of Vancouver Island. Interestingly, when he died in Victoria of a heart attack on August 2, 1877, at the age of 73, his funeral procession was possibly the largest in the history of B.C. He is interred in the Ross Bay Cemetery.

Appointed Commander-in-Chief, Pacific Station in 1857

The next person to know is Rear Admiral Robert L. Baynes, a hero of Great Britain’s Greek War of Independence and the Crimean War (and who turned out to also be a hero in the Pig War). Baynes Sound in British Columbia is named for him, and the town of Ganges on Saltspring Island and the waters offshore, Ganges Harbour, are named for his flagship, HMS Ganges.

He was appointed Commander-in-Chief, Pacific Station in 1857 and refused to obey orders from the Governor Douglas to land marines on San Juan Island to engage American soldiers. He is credited with adopting a policy of non-intervention that helped to defuse what the British refer to as “The San Juan Boundary Dispute of 1859.”

Later promoted to

Admiral of the Fleet, the highest rank in the Royal Navy

Sir Geoffrey Thomas Phipps Hornby was a Royal Navy officer who saw action at the capture of Acre in November 1840 during the Egyptian–Ottoman War.

Following a change of government, Hornby became commanding officer of the frigate HMS Tribune on the Pacific Station in August 1858. He is largely credited with using peaceful diplomacy to facilitate and end to the rising tensions on San Juan Island, eventually overseeing the transfer of ownership to the United States.

The naval historian Sir William Clowes, who knew Hornby well, wrote that “… he was a natural diplomatist, and an unrivaled tactician; and, to a singular independence and uprightness of character, he added a mastery of technical detail, and a familiarity with contemporary thought and progress that were unusual in those days among officers of his standing.”

Worked for the Hudson’s Bay Company

Ran the Belle Vue Sheep Farm

Charles John Griffin was a well-respected herdsman, originally from Ireland. A no-nonsense kind of guy, Griffin was adept at managing the HBC’s large estate despite the constant harassment by United States customs agents attempting to levy taxes for the livestock grazing on what they considered their land.

A probably apocryphal story claims that, upon learning that Lyman Cutlar had shot one of his pigs, Cutlar said to Griffin, “It was eating my potatoes,” to which Griffin replied, “It is up to you to keep your potatoes out of my pig.”

The legacy left by Charles Griffin and his staff is still apparent. Many of San Juan Island’s roads today trace the paths of the sheep runs carved through forest and around the tremendous rocks left behind by the glaciers.

The Rest

King of Prussia

First German Emperor

Survived 3 assassination attempts

There are two more characters in this strange saga. The first is the German Emperor and King of Prussia, none other than His Imperial and Royal Majesty Kaiser Wilhelm I (that was his preferred title at one point, which was much shorter than his formal title).

Under the leadership of Wilhelm and his Minister, President Otto von Bismarck, Prussia achieved the establishment of the German Empire as a politically and administratively integrated nation in 1871. Wilhelm was described as polite, gentlemanly and – while a staunch conservative – more open to certain classical liberal ideas.

A highly-regarded, internationally-known head of state, he was an excellent choice for a neutral third party arbitrator when the US and Great Britain decided to settle the Pig War boundary dispute.

Large Black boar

Fond of tubers

The last and most well-known player in this porcine parable is, of course, The Pig…the lone fatality in the war that bears its name. It was reportedly either a Large Black or Birkshire boar.

Berkshire pigs are a rare breed of pig originating from the English county of Berkshire. They’re prized for their juiciness, flavor and tenderness.

The Large Black, occasionally called the Devon, Cornwall Black or Boggu, is a breed of domestic pig also native to Great Britain. It is a hardy and docile pig, with Large Black sows known for having large litters. The breed’s foraging ability make it particularly useful for extensive farming and it was popular in the early 1900s.

Regardless of species, these pigs are large and always on the lookout for their next meal…even if it doesn’t belong to them.

The Story

In 1818 – just three years past the end of the War of 1812 – the United States and Great Britain signed a treaty that set their boundary along the 49th parallel from Minnesota to the Rocky Mountains (then known as the Stoney Mountains).

The tenuous peace lasted through the 1840s, when the Hudson’s Bay Trading Company – already in the Pacific Northwest – began finding it increasingly difficult to prevent American settlers from moving north of the Willamette Valley in Oregon Country.

In 1843 at Fort Vancouver (in present-day Vancouver, Washington), Hudson’s Bay Company Deputy Chief Factor James Douglas received orders from across the Atlantic to select a site on Vancouver Island to the north to establish a new fort. He selected an area known to Natives as “Camousun,” and renamed it “Victoria.” Within the year, the stockade, stores, warehouses, and private quarters inside the fort were finished.

Shortly thereafter, British supply ships began stopping at Fort Victoria before heading to Fort Vancouver, marking the effective end of the Hudson’s Bay Company’s transfer of their western headquarters.

Boundary disputes between Oregon Country of the United States and the Columbia District of Great Britain were resolved on June 15, 1846, with the signing of the Oregon Treaty (sometimes erroneously called the Treaty of Washington) by continuing the 49th parallel boundary from the Rocky Mountains to the Pacific Coast. It should be noted – however – that Fort Victoria is significantly south of the 49th parallel.

From Article I of the Oregon Treaty:

“From the point on the 49th parallel of north latitude, where the boundary laid down in existing treaties and conventions between Great Britain and the United States terminates, the line of boundary between the territories of Her Britannic Majesty and those, of the United States shall be continued westward along the said 49th parallel of north latitude, to the middle of the channel which separates the continent from Vancouver’s Island; and thence southerly, through the middle of the said channel, and of Fucas Straits to the Pacific Ocean.”

However, there are actually two straits that could be called the middle of the channel: Haro Strait, along the west side of the San Juan Islands; and Rosario Strait, along the east side.

In 1846 there was still some uncertainty about the geography of the region. The most commonly available maps were those of George Vancouver, published in 1798, and of Charles Wilkes, published in 1845. In both cases the maps are unclear in the vicinity of the southeastern coast of Vancouver Island and the Gulf Islands. As a result, Haro Strait is not fully clear either.

Both sides continued to dispute the treaty’s language for another ten years. Then, in 1856, US and Britain set up a Boundary Commission to resolve a number of issues regarding the international boundary. Because the HBC had been grazing sheep on San Juan Island for several years, they claimed the islands for Great Britain.

Both sides continued to dispute the treaty’s language for another ten years. Then, in 1856, US and Britain set up a Boundary Commission to resolve a number of issues regarding the international boundary. Because the HBC had been grazing sheep on San Juan Island for several years, they claimed the islands for Great Britain.

From the start, the British maintained that Rosario Strait was required by the treaty’s wording and was intended by the treaty framers, while the Americans had the same opinion for Haro Strait. The two sides continued to discuss the issue into December 1857, until each side’s argument was clear and neither could be convinced of the other. At the final meeting, the British suggested a compromise line through San Juan Channel, which would give the US all the main islands except San Juan Island. This offer was rejected and the commission adjourned, agreeing to report back to their respective governments.

For the next two years, the Hudson’s Bay Company continued their cattle farming operations on San Juan Island. During that time, American tax collectors repeatedly attempted to collect taxes for the grazing of cattle on the island…yet, when threats of Indian attacks arose, American and British citizens united inside the HBC stockade for defensive purposes. It was those threats that led to the transfer of Captain George Pickett, commander of Company D of the 9th Infantry Regiment stationed at Fort Steilacoom, to Bellingham Bay to help quell the Indian insurgency of 1856.

The discovery of gold in the area brought hundreds of Americans from Oregon and California to Vancouver Island. Those miners who didn’t strike it rich – which was just about everyone – often settled in the area, prompting American surveyors to begin laying out plots of land on San Juan Island…to the great annoyance of the Hudson’s Bay Company.

The Stage is Set

By 1859, the British were still fully engaged in farming operations on San Juan Island, but by this time just shy of 30 American settlers had arrived to homestead – including Lyman Cutler – tipping the population imbalance in favor of the Americans. Cutler’s homestead was closest to the HBC farming headquarters, where sheep and pigs grazed freely. The map on the right was drawn by 2nd Lt. James Forsyth, showing the location of the American settlements in comparison to the HBC operation.

By 1859, the British were still fully engaged in farming operations on San Juan Island, but by this time just shy of 30 American settlers had arrived to homestead – including Lyman Cutler – tipping the population imbalance in favor of the Americans. Cutler’s homestead was closest to the HBC farming headquarters, where sheep and pigs grazed freely. The map on the right was drawn by 2nd Lt. James Forsyth, showing the location of the American settlements in comparison to the HBC operation.

Cutler proceeded to build a fence on his property in order to protect the third-of-an-acre of potatoes he’d been trying to cultivate. The loose HBC pigs, always looking for their next meal, repeatedly knocked over one side of Cutler’s fence to uproot his potatoes. He complained to Charles John Griffin, the Irishman in charge of HBC farming operations, but was informed instead that the HBC believed Cutlar to be trespassing on British land.

Days later on June 15, finding yet another pig uprooting his potatoes, Lyman Cutler loaded this double-barrel shotgun, shouldered this ammunition bag and chased the pig through the woods. At the edge of the treeline, the pig reportedly stopped to look back at Lyman, giving Cutler the moment he needed to raise the rifle and shoot it dead…thus resulting in the first, last and only casualty of the impending “war.”

Cutler proceeded to find Griffin and tell him what happened. He even offered to pay $10 for the pig…a fair price on the east coast where there are pigs aplenty but possibly not what a pig was worth in the territorial American west. Griffin responded that the pig was worth $100 and the two men had words before the dispute was brought to Governor James Douglas.

Now, remember that General William Harney had been placed in charge of overseeing American forces in the northwest. For Harney, that’s tantamount to an administrative transfer into obscurity. Still, the man has a job to do, and it was during one of Harney’s infrequent visits to his scattered commands that he reached out to Governor Douglas in Victoria and was told about the pig incident. Seeing an opportunity to reinvigorate his career, Harney sailed to San Juan Island to visit with American settlers and devised a way to justify sending troops to the island. Eventually, he circulated a petition requesting military aid to help defend against alleged Indian attacks, which the island homesteaders eventually signed. Harney then took the petition to Fort Bellingham to meet with Captain Pickett.

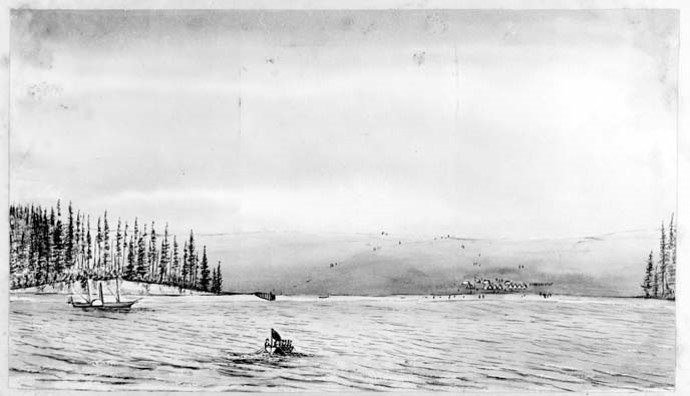

Pickett’s first camp was located just west of the Hudson’s Bay Company dock (left center). This watercolor was done by a Royal Navy midshipman while standing on the deck of HMS Satellite. The date on the back of the painting reads July 27, 1859 – the very day Pickett landed.

The conical Sibley tents used at the US Army camp were shipped from Fort Steilacoom.

Pickett was given autonomy to act any way he saw fit on San Juan, and proceeded to transfer troops and supplies to the island – again from Forts Steilacoom and Bellingham – after issuing a proclamation that the entirety of the disputed area is American territory. Who or what he thought gave him that authority may never be known, but Governor Douglas obviously disagreed and in response sent a police force to the island as well.

In the following days, three British warships – the Satellite, the Tribune and the Plumper – arrived in the harbor with a thousand men and guns trained on the small American military encampment. The American ship – the Massachusetts – was also nearby and Governor Douglas began urging British military captain Geoffrey Hornby to land his troops and attack Pickett. Hornby refused, citing the need for cooler heads to win the day.

Under a blanket of fog, American Colonel Silas Casey (the father of U.S. Army engineer Thomas Casey, after whom Washington State’s Fort Casey is named) left Fort Steilacoom and landed reinforcement troops on San Juan Island. By August 10, 1859, 461 Americans with 14 cannon were opposed by five British warships mounting 70 guns and carrying 2,140 men.

A month-long standoff ensued, during which Governor Douglas ordered British Rear Admiral Robert L. Baynes to land marines on San Juan Island and engage the American soldiers. Baynes, like Hornby, also refused, deciding that “two great nations in a war over a squabble about a pig” was foolish. Local commanding officers on both sides had been given essentially the same orders: defend yourselves, but absolutely do not fire the first shot. For several days, the British and U.S. soldiers exchanged insults, each side attempting to goad the other into firing the first shot, but discipline held on both sides, and thus no shots were fired.

By the time President Buchanan found out what had been taking place on the other side of the country, he was desperately trying to keep the northern and southern states from collapsing into civil war with his “peace at any price” policy. He didn’t have the time nor the interest to deal with an international incident, so he instructed Gen. Harney to stand down and consult with others on how to proceed. Buchanan then sent General Winfield Scott to negotiate with Governor Douglas and resolve the growing crisis. As a result of the negotiations, both sides agreed to retain joint military occupation of the island until a final settlement could be reached, reducing their presence to a token force of no more than 100 men.

During the following years of joint military occupation, the small British and American units on San Juan Island had an amicable mutual social life, visiting one another’s camps to celebrate their respective national holidays and holding various athletic competitions. Park rangers tell visitors the biggest threat to peace on the island during these years was “the large amounts of alcohol available.” This state of affairs continued for the next 12 years. In 1866, the Colony of Vancouver Island was merged with the Colony of British Columbia to form an enlarged Colony of British Columbia.

In 1871, the enlarged colony joined the newly formed Dominion of Canada. That year, Great Britain and the United States signed the Treaty of Washington, which dealt with various differences between the two nations, including border issues involving the newly formed Dominion. Among the results of the treaty was the decision to resolve the San Juan dispute by international arbitration with Kaiser Wilhelm I of Germany chosen to act as arbitrator.

Wilhelm referred the issue to a three-man arbitration commission which met in Geneva for nearly a year. On October 21, 1872, the commission decided in favor of the United States. The arbitrator chose the American-preferred marine boundary via Haro Strait, to the west of the islands, over the British preference for Rosario Strait which lay to their east, thereby finalizing the decades-long dispute and giving sole ownership of San Juan Island to the Americans.

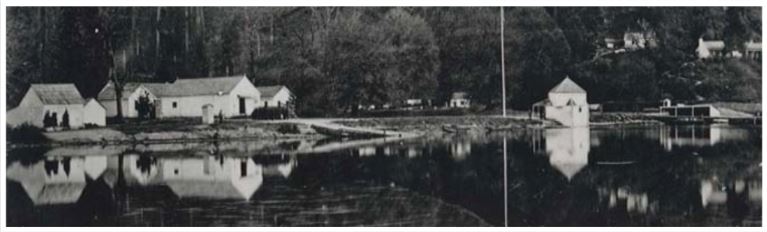

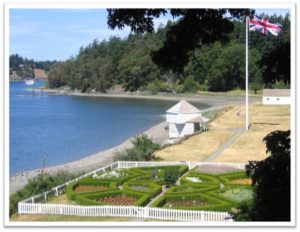

The blockhouse and the storehouse still stand at English Camp today.

On November 25, 1872, the British withdrew their Royal Marines from the British Camp. The Americans followed by July 1874…bringing closure to the Pig War.

Today the Union Jack still flies above the “English Camp,” being raised and lowered daily by park rangers, making it one of the few places without diplomatic status where U.S. government employees regularly hoist the flag of another country.

So what lessons can be derived from this interesting and little-known chapter of Washington’s history? I like to remind myself at times that in life – metaphorically speaking – pigs will always be trying to eat our potatoes. What’s important is to take a deep breath, have some bacon, and know that you can grow more potatoes.

Pingback: Museum board president calls for new way of managing historic site | Fort Steilacoom